WordsOfRebellion

Art-practice essay research focuses on the concept of "democracy". It is situated in the current context of the Chilean revolt (2019-). From a personal narrative, the analysis references the situation in Chile, explores contemporary Chilean media art after the dictatorship, proposes science and technology as fields of power, and embraces art as a space of resistance to think, feel and relate.

produced by: Camila Colussi

“Evadir, no pagar, otra forma de luchar”

“Avoid, don’t pay, another way of fight”.

October 18th, 2019.

The starting day of the current Chilean civil rebellion.

Chile protests: Unrest in Santiago over metro fare increase

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-latin-america-50106743

The destruction of the subway.

Destruction in the streets.

Chaos. Confusion.

From my perspective; from London, UK; through Youtube, Facebook, the online news and Whatsaap: everything was destroyed. The country was on fire. I never thought that could really happen. In shock. Everybody in shock.

The president said: “Chile is at war”

If Piñera wants to wage war in Chile he should fight the real enemy: inequality

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/oct/23/chile-protest-war-pinera-inequality

State of Emergency and curfew. Like in the old days of the dictatorship. The past came into the present.

But, it’s enough.

We can’t afford the bills while the rich get richer.

It’s the tiredness of abuse.

The feeling of injustice.

The need of destruction to be reborn.

Friday by Friday, people rose up into massive protests on the streets that just recently diminished by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The protests evolved in multiple layers of meaning: political development, critic discussion, communal support, love, friendship, respect. At the same time, it showed the violent face of the government through the actions of the police and the Army. Murder, rape, mutilation, prosecution. Serious human rights violations. All spread in social media. So many hours watching violent videos of brutal and unjustly repression. How could this be happening in a democracy? Where is the country where I used to live? This is not possible in the 21st Century. Denial and confusion. Blurred eyes. What it’s happening?

Chile protests: UN accuses security forces of human rights abuses

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-latin-america-50779466

No. That’s not how democracy looks like.

Democracy fell down one day to another. I never questioned it. Many things could be wrong in politics. It is dirty and disappointing, but I thought that was the way it is. I believed in our democracy anyway. But now it is clear that it was never there.

Many authors are writing about the way this rebellion was expected to happen. It did not come out of the blue. It was hidden under the carpet.

‘Chile Woke Up’: Dictatorship’s Legacy of Inequality Triggers Mass Protests

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/03/world/americas/chile-protests.html

One of the consequences of these months of protests is the path for a brand new Chilean Constitution (Encuentro por un Plebiscito para una nueva Constitución, 2019.) The current one was written in dictatorship and it’s been point out as one of the obstacles for social change, justice and equality. (Heiss and Szmulewics, 2018). Further, it draws the lines to define the country we want to be, for instance, the guaranty of human and social rights, the recognition of the original cultures, the relation with the market, science, culture, among others. If we have the chance of writing a new Constitution, what do we understand by democracy and how should we build the democratic society that we are fighting for?

The current Constitution establishes that: “Chile is a democratic Republic” (Chile. Jurídica, 2014). But, after the recent months, this sentence feels empty. Democracy must be more than elections. Democracy must be more than majorities and minorities. Democracy must be more than power, politics, territory, sovereignty and govern. Democracy must be more than a method. Democracy must be more than human.

BLURRED DEMOCRACY

Looking for a definition

My first approach comes from confusion. I built the piece “Blurred democracy” as a mirror of my disorientation. The work presents audio recordings of the recent protest in Chile, while stands the word “democracy” written in copper wire. The word looks “blurred” by the intervention of vibrating motors. "Blurred democracy" was the starting point of research for a definition that could explain what was wrong in Chile.

“Democracy: a method for social organization that recognizes, respects and values the diversity of actors that make part of it and seeks for the best ways of coexistence.” That’s was my first attempt of definition. My illusion.

Let’s try from the beginning.

“The word ‘democracy’ comes from the Greek and literally means rule by the people. It is sometimes said that democratic ideas have been handed down to us from that time. In truth, however, this is an unhelpful assertion. The Greek gave us the word but did not provide us with a model (…) The Greek had a little or no idea of the rights of the individual, an idea that is tied up with the modern concept of democracy. Greek practice granted the right of political participation to only a small minority of the adult inhabitants of the city. When those granted this right were able to take political decisions, they did so by a direct vote on issues, which is very different from the system of representative government that has developed in the west in the past two centuries.” (Birch, 1993, p. 45)

The Greek origin of the word might be not just a distorted assertion for our contemporary days, but also quite foreign for the Chilean people. It's not enough to jump into the complexity of the colonized, independent, aristocrat, socialist, dictatorial, capitalist Latin American history of the country. Maybe that's the first clue of the error.

The turn into a modern definition moves into the method.

“The term ‘democracy’, in its modern sense, came into use during the course of the nineteenth century to describe a system of representative government in which the representatives are chosen by free competitive elections and most male citizens are entitled to vote.” (Birch, 1993, p. 46)

Thus, if we cling to the methodological definition, abusive and authoritarian policies can be raised in the name of democracy. In many interviews, Sebastián Piñera, current President of Chile, remarks that he was democratically elected. He seems to justify his decisions based on that fact while denying the national and international accusation of Human Rights violations or the fall of popular approval (around 6%) that questions the representative governance through his decisions. Franco “Bifo” Berardi explains it this way:

“If democracy means “the rule of the majority of people”, (…) then, in the year 1923, democracy in Germany was Adolf Hitler and in the year 2016, democracy in the United Kingdom is Brexit. If we want to find out a political strategy for the future, we cannot think that the problem is to re-establish democracy. We need to establish something much more concrete than democracy. The health of people, freedom in daily life, re-distribution of wealth, the possibility of having public education, publish health systems, the possibility of living well. (…) Democracy might be the methodology for obtaining these aims, not the aim itself.” (E-Flux, 2019)

After all, I was not that confused when seeing the recent events in Chile. It was not about my blurred ayes, but a blurred democracy.

“In defining and discussing democracy in the twentieth century, there have been two sources of confusion. One source of confusion is that the term has been used not only to describe a system of government but also to describe other social relationships. Thus, Americans [United States of America] have said that their country not only has a democratic set of political institutions but also has or is a democratic society. (…) Thus, a democratic society, in the American sense [United States of America], is one without hereditary class distinctions, in which there is something approaching equality of opportunity for all citizens. The term ‘democratic’ is used to indicate a degree of social equality, not a form of government” (Birch, 1993, p. 46).

This understanding of a “democratic society” gives certain characteristics for the social organization. Then, it would be not the same saying “Chile is a Democratic Republic” than re-writing it as “Chile is a democratic society” or a “social democracy”. It could deploy important differences.

“Do we keep asking? Do we keep voting? Do we take what ours? What do we do?” — US student

“WE ARE HUMANS!!” — A group of refugee protesters shouted

Fragments from the film “What is democracy?” (Taylor, 2018).

From the film “What is democracy?” (Taylor, 2018) I conclude two main ideas. First, the contradiction between a neo-capitalist democracy and second, the question for a fair, free and happy way of living. At the film, Wendy Brown — political theorist from the United States of America— establishes that, instead of the ruling for the people, it’s the ruled by profit and loss, by technocrats that follow algorithms. The government as a business (let's highlight that Sebastián Piñera is one of the richest businessmen in Chile). Our democracies are ruled by economical systems and not by the goal of social interests.

“It’s not choosing and deliberating about who we want to be, what kind of people we want to be, what we want to become, how we want to conduct ourselves, it’s simply living according to what (…) enhances value. What depreciates value? What brand might succeed? What brand will fail you?” (Taylor, 2018).

How should we live? That’s the question for the new Chilean Constitution and the future of Chile. That's the importance of re-thinking democracy.

After October 18th and for the first time, I started to understand many things about the Chilean dictatorship. You can read about it, your parents could tell you stories, but living it is completely out of parameter. And I was in shock. This can’t be happening. I got obsessed watching the atrocities through the Internet as I felt I needed to see the truth. I couldn’t sleep. I couldn’t think of anything else than Chile. I felt that I was in limbo: my body stayed in the UK, but my existence was torn apart in an emotional connection that trapped me to the other side of the world. I was living my life on the screen of my computer / my mobile. My existence turned digital somehow. I wanted to be connected to Chile as an attempt to be there. It took me several months to realize that I was not.

In 2009, the Mexican artist Teresa Margolles exhibited at the Venice Biennale the piece “What else could we talk about?” to bring out the violence in Mexico. That’s exactly the point. In the current Chilean context, What else could we talk about? This situation hit my life and my art practice. How to see/feel/think about art in this context? What are the potentials of the Internet and the technologies from the digital for the Chilean task?

ART, TECH and DEMOCRACY

The development of the Internet and digital technologies brought hope for a new democratic opportunity in the 20th Century. The revolution of information, science and communications. Though, we’ve already seen the twist: control through data-mining, digital surveillance, biogenetics, among others.

“The most salient trait of the contemporary global economy is, therefore, its techno-scientific structure. (…) advanced capitalism both invests and profits from the scientific and economic control and the commodification of all that lives.” (Braidotti, 2013, p. 59)

Rossi Braidotti in “The Posthuman” alerts us about the play of capitalism in the current times of science and technology. Already in 1984, Donna Haraway identified these fields as the power cards of the future. "Cyborg Manifesto" describes a new era of data domination where information would structure a new kind of society. For that reason, she challenges socialist-feminist politics to take place in these fields. (Haraway, 2016) If science and technology are the centres of the power of the future, they are also the place for the resistance.

How to look at the Chilean revolution through the possibilities of science and technology? How to approach to the question of democracy from these fields?

Cybersyn

Cybersyn was a state technological project developed in Chile in the late 1960s and the beginning of the 1970s. Under the cybernetics studies of Norbert Wiener and the direction of Stafford Beer, its goal was to incorporate cybernetic strategies into the economic administration of the new socialist country. It looked like the cybernetic ideas could model social systems, predict complex networks behaviours, diminish the uncertainty around the creation of public politics, improve a centralized administration and offer numerical data for governmental decisions.

But the aim of the project was not only about efficiency. It should manifest the Chilean socialist model headed by the socialist President Salvador Allende (1970-73). For that aim, it should renew the communication between the government and the workers of the industries; its design should be inclusive and consider people’s opinion[1], and it should guarantee the industry autonomy and its workers at the same time that link them the centralized political administration. Cybersyn was the promise of a technological tool that stands from a socio-political ideology whose aim was for the creation of the new society.

I need to highlight the fact that Beer believed that the socialist revolution was not possible if the socio-political structure of governance was not changing. For that reason, Cybersyn was more than a strategy but a new organization of the whole society.

Despite the dream, the reality was an obstacle for the implementation of the project: Cold War times, not support from the directors of the industries, technical problems in a precarious country, socio-economic and political instability. In the end, Eden Medina observes that technologies aren’t independent of their contexts: they are affected by the historical narrative. In other words, technology development is not enough for the development of technologies and their impact on society.

DemocracyOS

What is democracy for the internet era?

“How can we get our representatives, our elected representatives, to represent us? Marshall McLuhan once said that politics is solving today’s problems with yesterday’s tools. So the question that motivated us was, can we try and solve some of today’s problems with the tools that we use every single day of our lives? Our first approach was to design and develop a piece of software called DemocracyOS.” (Mancini, 2014)

DemocracyOS[2] is an open-source App developed in Argentina (2014-) that gives information about Congress new proposals and allows citizens to vote on them. This would show people’s opinion and would encourage a stronger decision-making connection between the representatives and the citizens. The App was offered to the Argentinean traditional parties, but the project was rejected.

“And yes, we failed (…) We were called naïve, and we were. Because the challenges that we face, they’re not technological, they’re cultural. Political parties were never willing to change the way they make their decisions” (Mancini, 2014)[3]

In comparison with CyberSyn, here technologies were able to be developed properly and finished but, once again, technology doesn’t work by itself. Here, the problem was not technological but cultural. Technology is not enough to build a better world. That’s how I get more and more convinced about the influence of the arts. One kind of art that does not stay at the place of leisure or entertainment, but that shapes culture. Marx’s hammer. Art and humanities to stir up perspectives and sensibilities. Previously, we talked about the economical domain of economics in our political system. But it is not just there, it is in culture.

We can’t change democracies if the culture doesn’t change.

Art and Activism

Peter Weibel in “Global Activism: Art and Conflict in the 21st Century” traces “The Invention of the ‘Artivist’” (Altay, 2015, p. 57), locating relations between the recent art history and the global democratic crisis. First, he identifies the political implications of the development of participatory art in the early 60s. “Participation” is the word to pay attention here. Participation would have been radicalized with the use of recording technologies that put at the audience in the place of the artwork (Altay, 2015).

“Video, computer, and the network technology augmented the participatory options in the 1980s and 1990s to the point of interactivity. Media art established the viewer’s participation in the creation of the artwork in terms of mutual physical influence. In the Action and media art of the second half of the twentieth century, the audience practised intensified participation. Art became a field of action and the viewer the activist or actor. This experience in the field of art had to spill over into the social domain at some point” (Altay, 2015, p. 55).

Next, he describes the generation of net-based artists that would have criticized and intervene in the media technologies of the digital world that now we are actively part of. And finally, “Online, everybody is an author and a publisher, and in its final instance likewise a voter and a politician” (Altay, 2015, p. 57). If we could trace this participatory trend in the arts, what else could we expect from our socio-political culture?

Global observations from a book called "Global activism". But I'm not sure about it. There are global influences, of course, but it suppresses the complex realities at the different points of the world. It is not as simple to call it global. It has a taste of colonialism, mostly when it comes from west research.

Media arts in Chile

With the return of democracy (1990), Chilean artists opened their body of work into issues of them more or less related to the recent past. Valentina Montero, Chilean curator and media art researcher, analyses the development of media arts in Chile from 1990 until 2014 (Montero, 2015). She is particularly focused on political proposals. She categorizes three groups to understand the different approaches: (1) Enunciation, (2) de-construction and (3) neo-constructivism in a micro-politics level.

“Enunciation” considers art pieces that name, highlight or point out situations of political interest. Montero observes that enunciation is one of the common strategies in the years of “the return of democracy”. During the dictatorship, artists encrypted their works as a medium of protection and resistance to the dictatorial eye. Nelly Richard named it “the self-censorship”. Then, the new days of democracy were an opportunity to bring up what was unmentionable in the past.

Anyway, enunciation is a common practice in the arts. I classify my own work “Blurred democracy” under this label. But it was a problem for me. How could you manifest a political claim but stay in the safe place —and invisible place— of the white cube? How could this be a contribution to the social fight?

I consider the art practice as a process of multiple levels and extensions. Building up “Blurred democracy” was the possible approach from a specific sensibility in a specific moment of my creative process. It was part of thinking and feeling the political issue. Even though the piece did not bring solutions or interventions, it stands perspectives, sensibilities and activates a cultural imaginary. Montero concludes that “[enunciative pieces not only] highlight a state of affairs, but they also contributed to the construction of realities and ways of understanding the objects to be revealed and history itself.[4]” (Montero, 2015, p. 582)

The second classification is “de-construction”, and it refers to art pieces that problematize the technology itself. Many of these works follow the political speech of “technological appropriation”. In other words, the need to understand the machine: work with technologies from the position of knowledge. Work as an active creator and not just a consumer of industrial pre-determination. The open-source, DIY and hack artists are very strong to emphasise it. Also, many Latin American de-constructive pieces aim to:

- “Uncover technologies”, erasing any sensationalism produced by their “spectacular” effects.

- Use the “error” as an aesthetic of resistance and an ethic of disobedience. In addition, the transparency of a process.

- Tech-recycle, not only for “ecological” goal but due to precarious reality. A Latin American survival strategy.

- Manifest their hybrid Latin American identity.

Finally, neo-constructivism on a micro-politics level. “Art is not a mirror of reality but the hammer that shapes it[5]” (Karl Marx cited in Montero, 2015, p. 538). Still, Montero asks: “How could operate an experimental art that goes out to the streets nowadays? Until which point the public space occupation from the media arts can contribute to modify its social environment and not only represent it?” (Montero, 2015, p. 564).

Digital ethnography

One of the final aspects analyzed by Montero in her thesis is the use of social media in contexts as the “Arabic Spring”, the “15M” movement or in the Chilean student protests in 2011. She writes:

“[These protests] were organized and boosted from the cyberspace through social media (Blogs, YouTube, Facebook, Twitter) demonstrating that even when information and communication technologies are controlled by economic and political interests linked to corporations, it is still possible to produce, exchange and distribute contents more or less freely, encouraging horizontal citizen participation in the virtual and physical space”[6] (Montero, 2015, p. 568).

As in 2011, the current Chilean rebellion was possible by digital communication. It is popularly said that digital platforms are devaluating our social lives. In this case, I would argue the opposite. Social media stood as a powerful instrument of unity.

Through social media ideas and opinions are exposed, discussed and spread. Since October, we have been watching and sharing political analysis of the Chilean movement. Analysis that come from "the experts" as well as from the common people. We shared useful information to get updated and informed. Also, we brought back old news about political fraud to remind the abuse. We shared videos explaining the need for a brand-new Constitution. Many popular references —musician, actors, athletes—said a word despite the censorship and the threatening. We saw the police violence and we shared the images as acts of denunciation. We saw them to get to know what was happening along with the country. I cried with the register of beautiful protests. I sang, cried and laugh with them. You could see the courage, the hope, the spirit, the love of the protesters. All of this has been one of the keys for the resistance. Through all those images, an emotional bond was strengthened.

WhatsApp and GPS to get to know the location of your friends and family: are you safe?

Twitter to spread protest campaigns or protest activities.

Facebook to counterargument fakes news from the official media.

A lot of fake news from social media as well.

Alternative media to check the news and review the number of people dead, raped, abused, mutilated.

I was there. In social media. That was my location in this revolution. Despite my effort, it took me a while to admit that I was not in Chile.

When COVID-19 arrived, the social meeting was forbidden. The plebiscite for a brand-new Constitution is in pause. After the fight, the dead, the fire, the crisis; we've got nothing back. Thus, the fight must continue.

COVID-19 limited the protest to digital strategies. I imagined a performative intervention. I asked a friend to walk across the empty streets of Santiago with a speaker that would play the sound of the protests. I downloaded audios from plenty of videos that I found on the Internet and edited them in a composition. I wanted the sound of the streets back to keep the fresh feeling of the fight. My friend got enthusiastic about the idea and she bought a protective white suit and a breathing mask to graphic to the isolation context. I sent her my audios but she said: “This is not how the protest sounds like”. I mean, they were the audios of the protests, but they were not carrying the experience of the street. My friend suggested some modifications and described to me how it should sound like. That was the breaking point. Finally, I realized that I was not in Chile.

Sound composition: https://soundcloud.com/camilacolussi/protestlockdown2

I was not in Chile.

I am not in Chile.

I AM not.

I realized that my whole journey about Chile has been a sort of digital ethnography. I wanted to look at the face of the country that was being reborn. Without seeing it, I've been in the middle of that search. But the goal is wrong. Through the digital practice, I was not able to access to the country that I left. Nevertheless, I can build with my own digital experience.

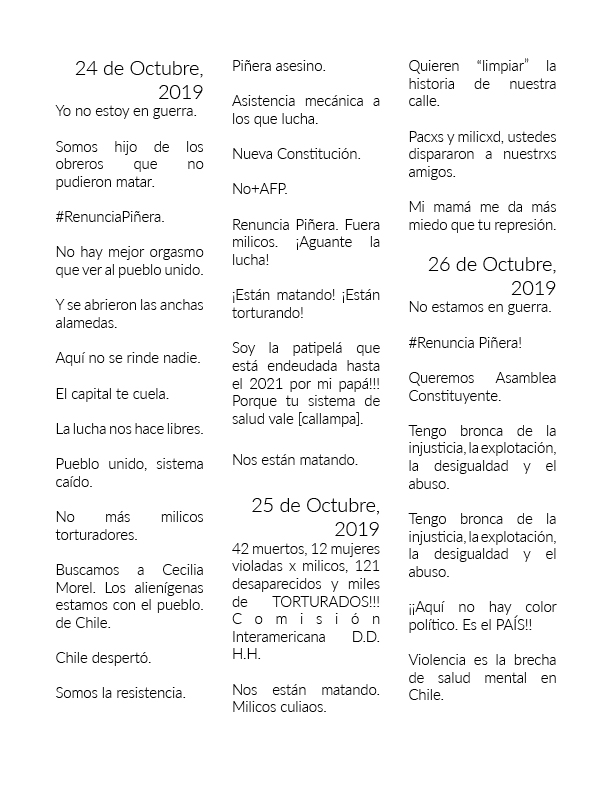

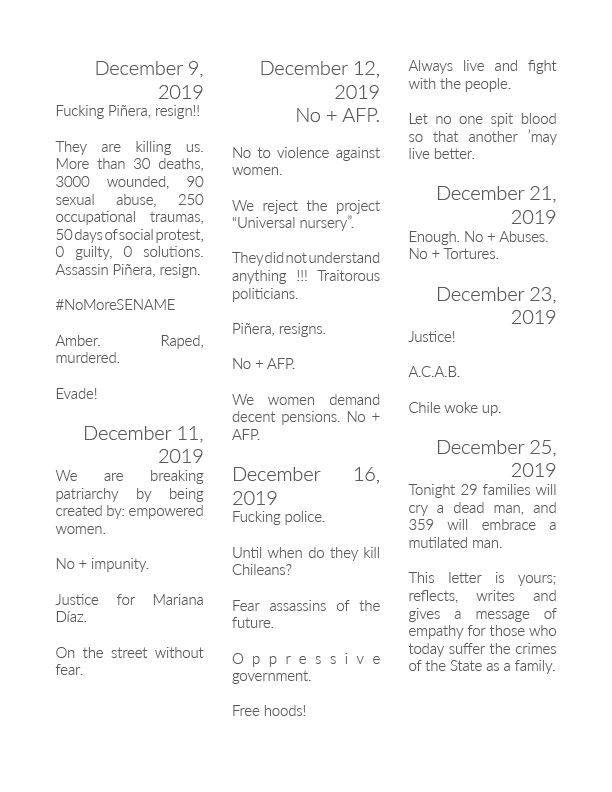

Soon in October, I collected some phrases from protest signs that protestors carried to the manifestations. I saw them through the images and videos shared on Facebook. I did it because I wanted to preserve the verbal expressions of the fight. Every day in Chile there was a new event that changed everything. One day was the First Lady comparing the protest with an alien manifestation, another day: the dead, other: the declarations of the police, other: the announce of the plebiscite, other: the university exam boycott, other: the fake news, on and on day by day —that’s why I could never sleep—. And this story was manifested in people’s signs. I stopped because it was too much. Too much information and too sad to try to recover my life in London. But now, I want to write a book. The aim is to research people on Facebook and Instagram and find the profiles that have been uploading photographs and videos of the protests. I’ll start with my friend Carla Motto. I will identify the images by the day they were uploaded to social media. I will consider October 18th to March 9th (the day before the lockdown and also millions of female Chileans in the streets due to the International Women Day).

SEEKING OTHER POSSIBILITY

I believe our democracies are in a blurred historical moment. They are not in crisis. Society changed and “democracy” doesn’t fit anymore.

André Haudricourt writes in 1962 a theory of “gestures”, published in Spanish (2019) under the name “El cultivo de los gestos. Entre plantas, animals y humanos” (“Cultivating gestures. In between plants, animals and humans”). The author compares cultivation and breeding of animals with the mentalities that gave birth to the metaphysics of East and West (Haudricourt, 2019). He's focused on the gesture of the human to the other, animal or plant. From the West, he identifies a gesture of human control and superiority. Meanwhile, in the East (exemplify as India and China), the human accompanies the growth of the plant and the behaviour of the animal. Here, the human doesn’t try to control because he/she understands the agency of the plant or the animal. Therefore, Haudricout indicates two different relational cultures. The philosopher Marie Bardet writes the epilogue of the book, and she projects this theory of gesture into socio-political relations. She says: “the way we approach and think our bodies influences in the way we think and practice the social, the technical and the political[7]” (Haudricourt, 2019). She criticizes the domination culture of the West, the one that established colonialism and slavery. The West gesture of domination declares what was better for the dominated. Please correct me when mentioning that West science pretends to know what is good for the plant than the plant. Also, I can include the Chilean political model here. Only the politicians know what is good for the people, because “people don’t know what they need”. Again, the gesture of domination.

I believe this is crucial for the development of the democracies of the future. We need to eradicate the culture of power and replace it for one in which actants accompany each other. Call me naïve, I know, but it’s true.

What if we bring the whole world of actants into democratic considerations? Jane Bennet in "Vibrant Matter" observes that human existence is not independent of others. Name it the bacteria in your gut or the iron in our blood. But humans have omitted that aspect and have assumed that we can run the world. Humans have been blind to the nonhuman networks inside and outside our bodies.

“What is the difference between an ecosystem and a political system? Are they analogues? Two names for the same system at different scales? What is the difference between an actant and a political actor?” (Bennett, 2010, p. 94)

In the beginning, I define democracy as a method of social organization. If now we think our politics as an ecosystem, is not a correct translation to say that we should organize the ecosystem. On the contrary. Following Haudricourt and Bardet gesture ideas, thinking democracy from ecology is a consideration to listen to the other, respect the other, accompany the other. Let’s live together for the first time.

The future is now

As Synco project or DemocracyOS, the democratic revolution needs more than changes in its method or structure. It needs more than technologies. It needs a cultural revolution of gesture. I believe art is one of the potential fields for its cultivation. It could be a space to experience new opportunities to relate with the other.

Art is space. A space to think, feel and relate. I took it from Manuela Infante —Chilean theatre director—. She said something like this: “Theatre is a space to philosophize” [8]. But not just as an exercise of thinking. Philosophize from the body, from the relation with the others, with your own existence standing in a sensitive world. A space for imagination, speculation, ideas, emotions, points of view. Art is a space for many things. As we saw earlier, could be also a space for information and complaint and saying the unmentionable. A space for history or to re-write history. We can’t define the whole species of spaces but, after all, a space that can open possibilities.

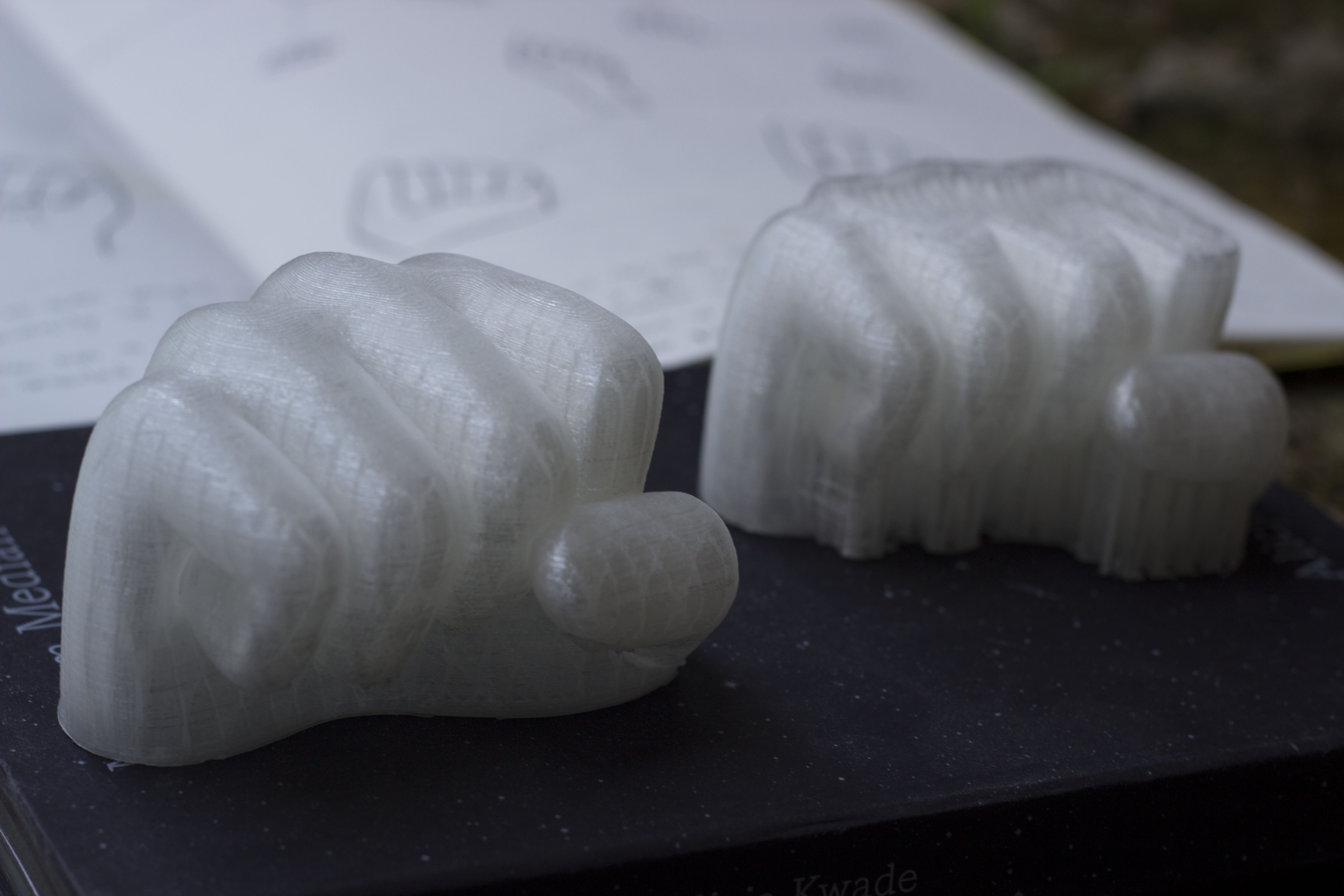

In 2011, while I was an undergraduate student, I made the piece “The future is now”. It was an installation in the front door of my university, where I located plaster fists to picture a frozen protest. It took place after the fall of the movement and the return to “normality”. With the installation, I wanted to confront the students that were coming back to classes and this return to normality.

The current Chilean protests (2019-2020) are having a different twist than the ones in 2011. Despite COVID-19, Chileans are anxious to come back to the streets and do not let themselves be defeated. The fight continues. I decided to make a new version of my plaster fists. This time, they would be made by a transparent material. LEDs would be illuminating them from the inside. In parallel, I’m building an online platform that asks the following questions:

What is democracy?

How should we live?

What is the difference between an ecosystem and a political system?

How can we include different humans and nonhumans in our institutions?

Every key from the keyboard is going to be an input to turn on the lights inside the fists. Every time someone answers/writes these questions, the light installation would be in action. In other words, every time the exercise of thinking about democracy through these questions would maintain the piece in a light dance. This project is still in progress.

I don’t know the answer for the future of democracy, but I believe that perspectives like the ones from Haudricout and Bannet are needed. I still don’t know how to embrace this kind of gestures/relations into my own art practice. For now, the work previously described introduces some of the questions that I consider could open the path for it. Let's revolution democracy.

Work-in-Progress:

Reference for further development:

------------------

[1] Even though the design aimed to include people’s opinion, Cybersyn was a secret government project.

[2] http://democracyos.org/

[3] At the end, Mancini and her team founded their own political party — El Partido de la Red, or the Net Party, in the city of Bueno Aires— establishing that, in case of being elected, they would vote according to the App. “That was our way of hacking the political system” (Mancini, 2014). And even though they didn’t reach a seat at the Parliament, they did enough noise to introduce the App in some political decision-making at the Congress.

[4] Translation by Camila Colussi.

[5] Idem.

[6] Idem.

[7] Translation by Camila Colussi

[8] Lecture: “Non-Human theatre”, by Manuela Infante (2019). Teatro a Mil, Santiago, Chile. https://teatroamil.tv/clases-magistrales/clase-magistral-manuela-infante/

Annotated bibliography

Birch, A.H. (1993). The concepts and theories of modern democracy. London: Routledge.

The author analyzes the concept of modern democracy, it’s origin and evolution over the years in the West. Also, it includes concepts such as liberty, democracy, rights, representation, authority and political power.

Haudricourt, A. (2019). El cultivo de los gestos. Entre plantas, animales y humanos. Buenos Aires: Editorial Cactus.

The text compares cultivation and breeding of animals with the mentalities that gave birth to the metaphysics of East and West. The author focuses on the gesture of the human to the other, animal or plant. Through the gesture in cultivation and breed, Haudricourt observes two different relational cultures with extensions into the sociopolitical models.

Montero, V. (2015). Arte de los medios y transformaciones sociales en Chile. Thesis. Universitat de Barcelona. Available at: http://arteymedios.org/biblioteca/publicaciones/item/72-arte-de-los-medios-y-transformaciones-sociales-en-chile-durante-la-transicion-politica (Accessed: 3 May 2020).

Thesis by the Chilean curator and media art theorist Valentina Montero. She analyses the development of media arts in Chile from 1990 until 2014. The book is particularly focused on political proposals. Montero covers socio-political and cultural contexts in Chile as well as contemporary philosophical theories that include: feminism, actor-network-theory, new materialism, among others.

Weibel, P. (2015). ‘People, politics, and power’, in Altay, C. Global activism: art and conflict in the 21st century. Karlsruhe: ZKM.

The chapter relates the crisis of contemporary representative democracies with the crisis of representation in the history of arts. It is focused on art and activism. Moreover, analyses and define concepts such as democracy, the people, the State, the citizen, the individual, the user, the net activist, the artivist.

References

Artaza, P., Candina, A., Esteve, J., Folchi, M., Grez, S., Guerrero, C., Martínez J. L., Matus, M., Peñaloza, C., Sanhueza, C., & Zavala, J. M. (2019). CHILE DESPERTÓ Lecturas desde la Historia del estallido social de octubre. Santiago: Universidad de Chile.

BBC News (2019) ‘Chile protests: UN accuses security forces of human rights abuses’, BBC News, 13 December 2019 . Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-latin-america-50779466 (Accessed: 25 April 2020).

BBC News. (2019). Chile’s capital in state of emergency amid unrest. BBC News. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-latin-america-50106743 (Accessed: 1 May 2020).

Bennett, J. (2010). Vibrant matter: a political ecology of things. Durham: Duke University Press.

Birch, A.H. (1993). The concepts and theories of modern democracy. London: Routledge.

Braidotti, R. (2013). The posthuman. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Chile. Jurídica. (2014). Constitución política de la República de Chile. Available at: https://www.leychile.cl/Navegar?idNorma=242302. (Accessed: 28 Abril 2020).

Del Campo, C. (2019). Encuentro por un Plebiscito para una nueva Constitución. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5h-kssQ-c80&feature=emb_logo (Accessed: 28 April 2020).

E-Flux. (2019). Franco “Bifo” Berardi on the future possibility of living well. [Podcast]. N.d. Available at: https://soundcloud.com/e_flux/franco-bifo-berardi-on-the (Accessed: 28 April 2020).

Haraway, D. (2016). Manifestly Haraway, Posthumanities. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Haudricourt, A. (2019). El cultivo de los gestos. Entre plantas, animales y humanos. Buenos Aires: Editorial Cactus.

Heiss, C., & Szmulewics, E. (2018). La Constitución Política de 1980, in: El Sistema Político de Chile. LOM Ediciones, Santiago de Chile.

Kaltwasser, C.R., (2019). If Piñera wants to wage war in Chile he should fight the real enemy: inequality. The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/oct/23/chile-protest-war-pinera-inequality (Accessed: 28 Abril 2020).

Mancini, P. (2014). How to upgrade democracy for the Internet era. Ted Talks. Available at: https://www.ted.com/talks/pia_mancini_how_to_upgrade_democracy_for_the_internet_era. (Accessed: 29 Abril 2020).

Medina, E. (2013). Revolucionarios cibernéticos. Tecnología y política en el Chile de Salvador Allende. Santiago: LOM.

Montero, V. (2015). Arte de los medios y transformaciones sociales en Chile. Thesis. Universitat de Barcelona. Available at: http://arteymedios.org/biblioteca/publicaciones/item/72-arte-de-los-medios-y-transformaciones-sociales-en-chile-durante-la-transicion-politica (Accessed: 3 May 2020).

N. Y. Times. (2019). ‘Chile Woke Up’: Dictatorship’s Legacy of Inequality Triggers Mass Protests. N. Y. Times. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/03/world/americas/chile-protests.html (Accessed: 2 May 2020).

The Guardian. (2019). Chile students’ mass fare-dodging expands into city-wide protest, The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/oct/18/chile-students-mass-fare-dodging-expands-into-city-wide-protest (Accessed: 25 April 2020).

Weibel, P. (2015). ‘People, politics, and power’, in Altay, C. Global activism: art and conflict in the 21st century. Karlsruhe: ZKM

What is democracy? (2018). [Online]. Directed by Astra Taylor. Zeitgeist Films. [Viewed 10 March 2020]. Available from Amazon Prime.