The Object and the Self :

a comparative interpretation with Yogic Philosophy and Object Oriented Ontology

produced by: Ankita Anand

“The truth cannot be found by argument, the soul itself is the truth…”

(Patañjali, Purohit, and Yeats 1987)

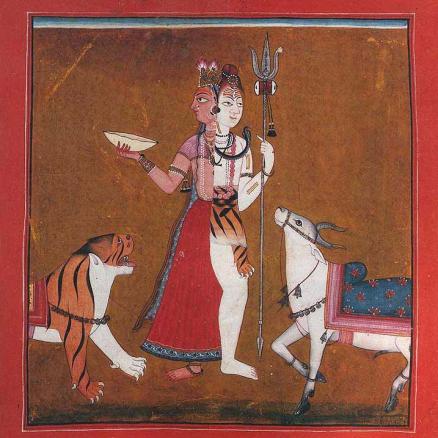

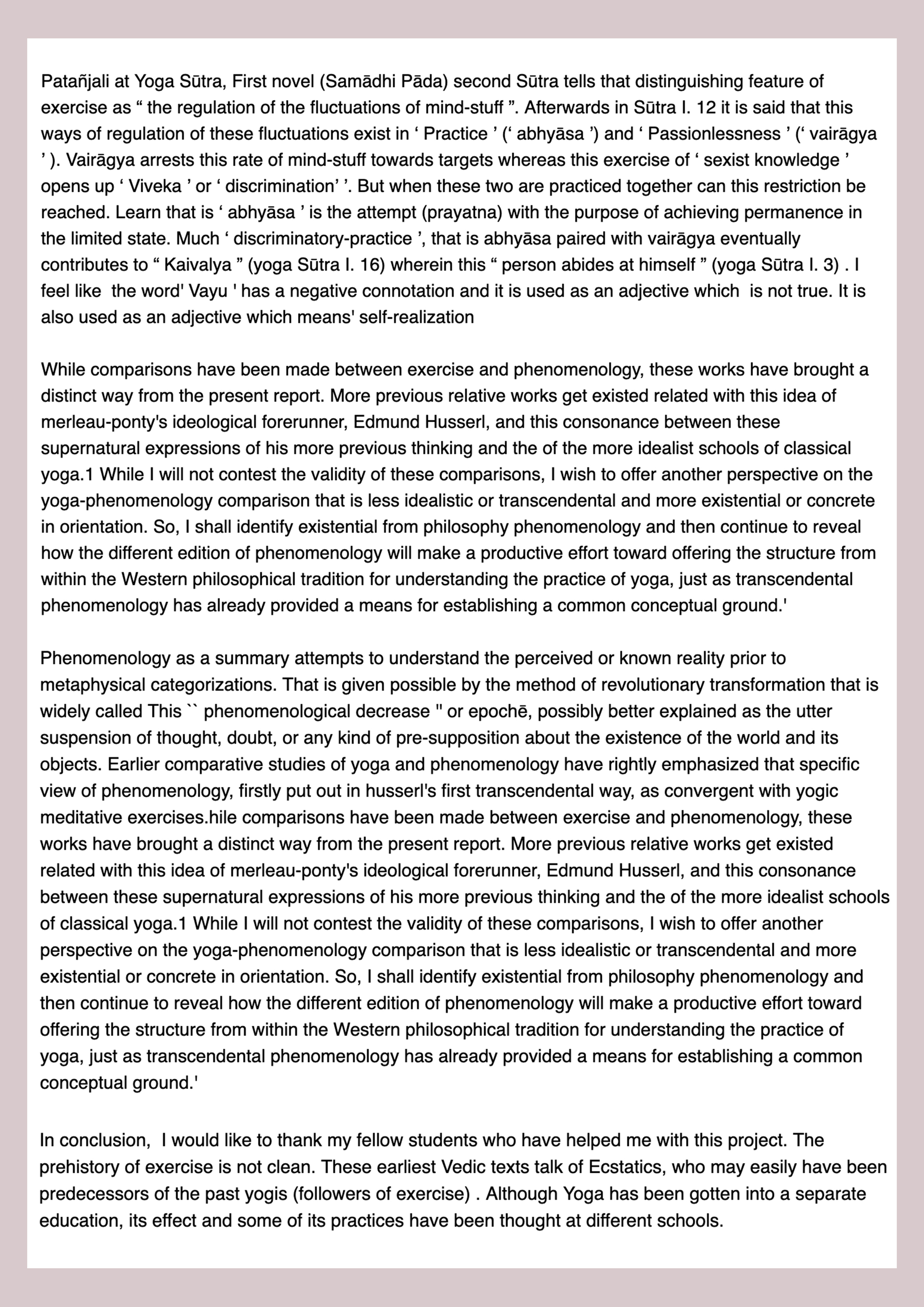

Fig 1: Siva, the Lord Whose Half Is Woman (Ardhanarisvara) Mankot School, Western Punjab Hills, c.1710-20 Opaque watercolour on paper, 21.3 X 20.5 cm

In this report I wish to explore how we define the object, the Self and its boundaries. The very way in which we perceive the world and handle life forms and non-life forms is dependent on our ideas surrounding the self and the other. These ideas of ‘being’ and phenomenology have been dealt with by various philosophers like Martin Heidegger, Merleau Ponty and Edmund Husserl. Contemporary philosophers such as Done Idhe, Robert Rosenberger and Peter-Paul Verbeek explore these through post-phenomenological approaches where they combine philosophical ideas with empirical investigation. However, Graham Harman suggested shifting our perspective entirely to an object-oriented one giving rise to Object Oriented Ontology. Feminist theorists such as Maria Puig de la Bellacasa, Karen Barad and Katherine Behar found lack of inclusivity in these philosophies and introduced their own approaches to the self and the object.

Nevertheless, in all these perspectives I find an eastern viewpoint lacking, especially when eastern philosophies have dealt with the idea of being and the self since ancient times. Hence through this report I wish to introduce eastern philosophy , in particular the yogic ways of looking at the mind and cognition, and how by exploring these in relation to existing theories can lead us to a more wholistic understanding of how we see the object and the self.

Introduction to yoga

Yoga, by the time it reached the West, has become skewed towards various different shapes and forms. Hence it becomes even more important to re-emphasise its origins. In this report I will be looking at yoga both as a text (Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras)[1] and as an experience. The word ‘yoga’ essentially means ‘union’, union with the ultimate reality, it offers to experience the nature of existence as it is. (Muller 1919, 313) This oneness or union if understood intellectually can lead to various issues[2], however, if this is understood experientially it can greatly enhance the experience of life. Hence yoga can be loosely called a system of technologies that uses only the human itself (no external means) to move towards inward experiences.

Rooted in existential reality, yoga acknowledges that our birth as a human being gives us a different spiritual possibility however it does not lend itself to believe that any other life or non-life form is superior or inferior. According to the yogic philosophy the human mind is divided into 16 different parts – 4 main ones being Buddhi (Intellect), Ahamkara (identity), Manas (memory) and Chitta[3] (awareness). Hence, intellect becomes only one aspect of our intelligence, in eastern philosophies it is not given the same degree of importance as it has enjoyed in the west. I will now look into knowledge and knowing as described by Patanjali (Patañjali, Purohit, and Yeats 1987) :

‘Sensation is the result of the identification of Self and intellect; they radically differ from each other, the latter serving the cause of the former; concentrate on the real Self; know that Self. Those who forget the Self and attend to intellect, thinking that intellect is everything, forget the host, attend to the servant. Self is the cause, intellect only an instrument. You can know the Self through Self only. Who can know the knower, how can he know the knower, except through himself?’

Here Patanjali suggests a difference between Self and the intellect – hence the intellect becomes a tool. In yoga the mind and the body are considered separate from the Self. The Self controls these tools but it shouldn’t mistake itself for the ‘servant’ instead of the ‘host'[4]. If we take this into consideration our thoughts lose significance and the existential and experiential aspects of life start coming forward. The Nyaya dualist tradition, which is a part of classical Indian philosophy of the mind, describes this notion of the self and the object (Chakrabarti 2001) :

“For the Nyaya, the self has extension but is not solid and so other physical objects can occupy the same space. This idea is necessary for the Nyaya view of the relation between self, consciousness and body. The self is the substratum of consciousness and the body is the receptacle of worldly enjoyment or experience.”

When the writer says ‘objects can occupy the same space’ this can be directly linked to some notions mentioned in Object Oriented Ontology discussed further on in the report. According to the Nyaya tradition the boundaries of the self are loose and can therefore expand to include other objects. Objects that surround us and their implications can be read and understood, however, when they exist and function these implications become more intricate and it becomes more complex to understand them through the intellect alone. It requires more experience-based and existential approaches to truly understand these relationships between self and the object. Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras are compact and precise because in the eastern tradition more emphasis was given to passing on knowledge experientially through a guru[5] rather than writing it down, as something written down could be misinterpreted in a variety of ways.

Given the experience based nature of yoga it seems contradictory for me to simply write a report and intellectually analyse and compare yoga to other philosophies. Although there are some aspects that can be understood through writing, the aim of this report is to expand our understanding of the Self and intelligence rather than merely compare texts.

Introduction to Object Oriented Ontology

Fig 2: Peter Fischli David Weiss, Nächtliche Heimkehr, 1984

Object Oriented Ontology (OOO) was pioneered by Graham Harman in four books: Tool-Being, Guerrilla Metaphysics, Prince of Networks and The Quadruple Object (Morton 2011, 164). OOO is part of speculative realist philosophy – it assumes that the world consists exclusively of objects and that human beings are just like any other object, bereft of a special privilege.

‘Alien Phenomenology’, written by Ian Bogost, uses OOO as a framework to explore philosophy. Through examples of the Turing test and Searle’s Chinese Room, Bogost (2012) explains how the notions of computation are always linked to human intelligence and understanding. He feels the machines deserve more study and appreciation of how they work independent of human use : “Yet, like everything, the computer possesses its own unique existence worthy of reflection and awe, and it’s indeed capable of more than the purposes for which we animate it.” (Bogost 2012)

Perhaps one way in which we fail to address objects with their due role in the world could be because of our limited scope of what we define as ‘intelligence’. There are rarely any systems in place to expand on the other aspects of life as mentioned in yogic philosophy - including in the Indian education system. If we change the idea we have of intelligence to a broader one then the way we think about objects would alter significantly. After all, the way we perceive objects is dependent on our awareness of the world. Bogost (2012) goes on to talk about ‘carpentry: constructing artefacts that do philosophy’ urging philosophers to be as much of makers as they are thinkers and hence reiterating the boundaries of the intellect. He mentions how writing is dangerous for philosophy and how it is ‘only one form of being’ (Bogost 2012, 90). In response to Bogost’s ‘carpentry’ and OOO I decided to explore how object-oriented programming can be used to express the more conceptual boundaries of self and object. The manner in which these objects interacted and overlapped revealed the fluid boundary of Self and object.

Fig 3 - 12: Cellphone, Ankita Anand, 2019

In making these different cells I suddenly became aware of the fact that I had created certain conditions and rules for them, however, when left to function on their own they behaved in an unexpected manner. Over a period of time the boundaries of each cell started to disappear and merge into the other. I then attempted to place many of these systems together which resulted in them harmoniously overlapping creating various patterns and textures. Below is a sped-up video I took of the screen. It made me re-think about my ideas and beliefs about the object and the self - to pay attention to these objects. As their creator or rule-maker I assumed I would know how they behaved, but this was far away from the truth. I wish to further extend this into an installation where the cells are controlled by a light sensor placed outdoors - a system of slow-reacting non-human interaction.

Video : Game of Life, Ankita Anand, 2019

Now if we go back to the yogic ways of seeing the mind and if we speculate that this system had some kind of an intelligence - it would not be merely to calculate its neighbours and exist intellectually - it would also compromise of its memory, the very shape of its form and what it is identified with. In terms of chitta, I believe realistically this aspect is difficult to extend to a non-human computational form but can be done speculatively. Broadening our ideas about cognition could lead to more inclusivity in designing Human-Computer Interaction and AI of the future. Whereas it is important to speculate on intelligence of these objects and interactions, it is also important to remember their realistic limitations. Inclusivity or ‘union’ (in yoga) should not be about extending privileges or favouring any particular group, it should come naturally as a result of the realisation of reality and not just because of an idea or belief.

Katherine Behar is an American artist and theorist who uses materialism and feminism to explore technology. Her projects like Anonymous Autonomous[7] and Data Cloud (A Heap, A Mass, A Rock, A Hill)[8] are good examples of theorists and philosophers can engage with objects and experiences to make sense of philosophies. Behar also proposed the idea of ‘Artificial ignorance’ which was a panel organised by her with emphasis on how we can discuss AI in terms of ignorance instead of intelligence. This is similar to yogic philosophy of identifying with the unknown - as knowledge can only be limited.

Fig 13 and 14 : Anonymous Autonomous, Katherine Behar, 2018 and Data Cloud (A Heap, A Mass, A Rock, A Hill), Katherine Behar, 2016

Object-Oriented Feminism (OOF)[9] is a theory proposed by Behar as a follow-up of the talk she attended by Ian Bogost on Alien Phenomenology and as a response to the ‘complex tensions’ (Behar 2016, 2) between object orientation and feminism. OOF proposes to address three important aspects : politics, engaging with people and histories of women, people of colour and the poor; erotics, OOF uses humour to address these entanglements; and ethics, trying to do the right thing even if it means being wrong. (Behar 2016, 3) Behar clearly proposes OOF as being open to wrongness, mistakes, inclusivity and humour. These aspects can be related to the non-intellectual side of our being; to not be afraid of being scientifically or logically wrong.

However, we cannot help but think that even with approaches like OOF, we will still end up describing things from our own perspective. At the end of it, it is still us writing and thinking about these objects and in turn analysing them. Nagel in Bogost (2012, 63) says “I want to know what it is like for a bat to be a bat. Yet if I try to imagine this, I am restricted to the resources of my own mind and those resources are inadequate to the task”. Perhaps to expand on these ‘resources’ as Nagel describes and go beyond the limitations of the mind we need some frameworks that explore other dimensions. One such framework could be a program called ‘Bhava Spandana’ offered by the Isha Foundation in Coimbatore, India[10]. It is a 4-day advanced yogic meditation program which is described as below (‘Bhava Spandana Program’ n.d.) :

The word Bhava literally means “sensation.” Spandana can be loosely translated as “resonance.” Through powerful processes and meditations, the Bhava Spandana Program creates an intensely energetic situation, where individuality and the limitations of the five sense organs can be transcended, creating an experience of oneness and resonance with the rest of existence.

The way the program has been described it can be a great opportunity to explore the self and object beyond the intellect. In order to know more about this for myself I interviewed three participants[11] who completed this program within the last three years.

One participant, who is a computer scientist, mentions how he had been ‘rigorously trained in quantitative methodologies and logical deductions’ (Gupta 2019) hence this program offered him an experience to life the way it is, existentially. It made him realise a sense of oneness and universality, not just as an idea, but as an experience. It made him pay attention to everything in nature - an ant, a leaf, seeing these objects as part of himself - further blurring the boundaries of the self and the object. This anecdote from the interview is reminiscent of how Jane Benette (2009, 4) in her book ‘Vibrant Matter’ describes a glove, pollen, rat, cap and stick by a pavement in Baltimore. She says ‘But they were all just as they were, and so I caught a glimpse of an energetic vitality inside each of these things, things that I generally conceive as inert’. (Bennett 2009, 4) To see things just as they are, as Benette describes, in all their vitality is what Bhava Spandana seems to offer.

The second interviewee mentions “…what I considered life wasn’t limited to people anymore but it was also apparent how important non-human life was; things such as water, food, trees, the earth itself”. (Mwanakhu 2019) This revelation of non-human life can also be linked to how Benett (2009) describes the vitality in things or ‘thing-power’. He goes on to say :

’an incredibly deep intelligence that saw no fault in anything but rather unified the world. With this deep intelligence the world wasn’t made up different objects that functioned autonomously, this deep intelligence revealed the world as a fantastic multiplicity, an orchestra of innumerable instruments.’ (Mwanakhu 2019)

Hence the program revealed not only the vibrancy of objects and life but also the universality of existence. The third interviewee with his example of a dog whistle explains how he realised there could be infinite events happening at this moment that we could be unaware of simply because they are beyond our five senses (Sahani 2019). It is interesting to note in all interviews how the program brings out experiences, feelings and emotions relating to the self and object, and how we perceive them. It states how the Self can expand, grow and include the other - whether it be another human or non-human. Can such experiences have more impact than reading about empathy, compassion, speculative fabulation and other OOO approaches? It seems such an encounter in life can be truly transformative and it eliminates the need to be tangled in philosophy.

As we have seen, various ideas discussed in the aforementioned OOO philosophies have parallels to the yogic philosophy in terms of inclusiveness and looking beyond the limitations of our mind. For a new framework in using and designing technologies and objects we perhaps need to look inwards and expand the way we experience the world. This means broadening our ideas of education and intelligence and stepping away from texts and theories that simply state ideas to more experience-based approaches that eastern influences, such as yoga, have to offer.

As a self-referential artefact, I present an essay on 'Yoga and Phenomenology' written entirely by a bot[12].

This artefact questions the intellect at various levels - if a bot can write an essay what does the future hold for philosophies and philosophers? On a different level this essay exemplifies how simple it can be for anyone to write about yoga and yogic philosophies, and the ways in which they can be misinterpreted - as the truth of yoga lies in its practice and as a way of being. I end this report by making a gimmickry of my own essay and comment on the boundaries I have presented myself and the reader with by merely writing about this.

Beyond this damaged body,

Beyond this fickle mind,

I am life. You are life.

Our normals may be different,

Our experiences so different!

But beyond all this nonsense,

Oh my dear brothers and sisters,

We are life, just life.

Someone maybe less agile, someone more,

Still we all are just a piece of life, nothing more.

Look beyond what the eyes can show,

Hear beyond what the ears can listen,

Feel beyond what you can touch,

And you will know, Oh my brothers and sisters,

We are just a piece of life, just a piece of life.

It's time to live.

– Aroon Sahani 2019

Footnotes

1. Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras are one of the earliest records of yoga written in 400 CE by Sage Patanjali. Sutra’s can be loosely translated to mean formulas. Since this was not meant to be an academic text the sentences are short and concise but need the right atmosphere to be understood in their full depth and dimension.

2. For example, you could consider everything as one and justify stealing from someone.

3. Chitta, not to be confused with mental awareness, can be defined as pure intelligence - awareness unsullied by memory or intellect

4. This might sound similar to the Cartesian dualism, however, this is considering the Self as being separate from both the body and the mind.

5. The idea of a guru is surrounded by skepticism due to various incidents of guru-like figures mishandling power - it hence becomes particularly difficult to follow one person - specially in the west as it would seem illogical. However, in places like India whether it be yoga or classical dance and music - you always have a guru whom you follow unconditionally. Similarly quoting just a few gurus in my report might seem one-sided but it is important to not analyse this aspect logically bearing in mind cultural differences.

6. Referring to memory held in your entire body rather than just the mind. Hence it relates to ‘embodied cognition’ which is the idea that cognitive functions of an organism are shaped by aspects of their entire body.

7. Anonymous Autonomous is an interactive installation that transforms office chairs into driverless cars. The aim of the work is to provoke processes that are contradictory to American values such as individualism, freedom and car culture. (http://www.katherinebehar.com/art/anonymous-autonomous/index.html)

8. Data Cloud is a physical mound of keyboard keys to present data as something weighty, unwieldy and physical. (http://www.katherinebehar.com/art/data-cloud/index.html)

9. I am aware that comparing a feminist approach (OOF) to yogic philosophy written by Patanjali, a male, could be problematic. However, in yoga there is an emphasis on the balance between the masculine and feminine energies but no need for strong identification with any one of these, as life is a manifestation of both. In my report I would like to shift the focus away from this gendered discourse to the more inclusive and interdependent nature of reality.

10. I have myself not taken part in the program

11. Link to interviews : https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1PZVQ-eCGMWafi7TfFNdV1w_LF8yZQmnA?usp=sharing

12. a ‘bot’ is a device or piece of software that can execute commands either automatically or with minimal human intervention. For this essay I used the following website : https://essaybot.com/

Annotated Bibliography

Bogost, Ian. 2012. Alien Phenomenology, or, What It’s like to Be a Thing. Posthumanities 20. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

In this book Bogost introduces Alien Phenomenology which is a branch of Object Oriented Ontology which aims to shift the centre of philosophical thinking to a non-human one through speculative thought. In the fourth chapter ‘Carpentry’ he urges philosophers to be makers however he himself is caught in entanglements of philosophy and resorts to writing a theory about it.

Povinelli, E. 2016 The World is Flat and Other Super Weird Ideas in Behar, Katherine, editor. Object-Oriented Feminism. University of Minnesota Press

Povinelli draws on Immanuel Kant, Deleuze and Graham Harman’s theories of philosophy. She takes the three aspects of Harman’s object-oriented ontology and relates them to three works by Karabing Film Collective. She concludes with a comparison of Meillassoux and Harman however fails to incorporate any non-western philosophies.

Religious Ritual in a Scientific Space: Festival Participation and the Integration of Outsiders - Robert M. Geraci, 2018

Geraci takes an ethnographic field research to understand how the Ayudha Puja in south india brings together westerners, non-westerns and the science community. Being a more ethnographic approach it does not take into consideration the links between spirituality and science beyond the bringing together of communities. Being a westerner he also approaches the festival from an intellectual perspective focussing more on the ‘sanskritization’ as labelled by M. N. Srinivas.

References:

‘Agential Realism, Social Constructionism, and Our Living Relations to Our Surroundings: Sensing Similarities Rather than Seeing Patterns - John Shotter, 2014’. n.d. Accessed 22 February 2019. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0959354313514144.

Ascott, Roy, ed. 2000. Art, Technology, Consciousness: Mind@large. Bristol, UK ; Portland, OR: Intellect.

Behar, Katherine, ed. 2016. Object-Oriented Feminism. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Bennett, Jane. 2009. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Duke University Press. https://www.dawsonera.com:443/abstract/9780822391623.

‘Bhava Spandana Program’. n.d. Accessed 22 April 2019. http://www.ishayoga.org/en/advanced-programs/bhava-spandana.

Bogost, Ian. 2012. Alien Phenomenology, or, What It’s like to Be a Thing. Posthumanities 20. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Chakrabarti, Kisor Kumar. 1999. Classical Indian Philosophy of Mind: The Nyāya Dualist Tradition. Albany, N.Y: State University of New York Press.

Clothier, Ian. 2014. ‘The Changing Boundaries of Knowledge Between Māori Awareness and Western Science’. Leonardo 47 (5): 513–14. https://doi.org/10.1162/LEON_a_00829.

Collier, Andrew. 1994. Critical Realism: An Introduction to Roy Bhaskar’s Philosophy. London ; New York: Verso

Gupta, Shubham. 2019. Bhava Spandana Interview by Ankita Anand . In person. London, UK.

Ihde, Don. 2016. Husserl’s Missing Technologies. Fordham University Press. https://doi.org/10.5422/fordham/9780823269600.001.0001.

‘Katherine Behar - News’. n.d. Accessed 21 February 2019. http://www.katherinebehar.com/shows/index.html.

Kobayashi, Hill Hiroki. 2015. ‘Research in Human-Computer-Biosphere Interaction’. Leonardo 48 (2): 186–87. https://doi.org/10.1162/LEON_a_00982.

McIvor-Tyndall, Alexander J. (Alexander James). n.d. ‘Cosmic Consciousness The Man-God Whom We Await’. Http://Www.Gutenberg.Orgfiles/14002/14002-8.Txt. Accessed 20 March 2019. http://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/14002/pg14002-images.html.

‘MediaArtHistories Archive: Cultural Software - Materiality and Abstraction in 60s Art and Technology’. n.d. Accessed 25 April 2019. http://pl02.donau-uni.ac.at/jspui/handle/10002/716.

Muller, Max. 1919. The Six Systems of Indian Philosophy. New York: AMS Press Inc.

Mwanakhu, Joshua. 2019. Bhava Spandana Interview by Ankita Anand . In person. London, UK.

Norman, Donald A. 2002. The Design of Everyday Things. 1st Basic paperback. New York: Basic Books.

Norman, Donald A. 2005. Emotional Design: Why We Love (or Hate) Everyday Things. New York: Basic Books.

Patañjali, Purohit, and W. B Yeats. 1987. Aphorisms of Yôga. London; Boston: Faber.

Prabhu, H. R. Aravinda, and P. S. Bhat. 2013. ‘Mind and Consciousness in Yoga – Vedanta: A Comparative Analysis with Western Psychological Concepts’. Indian Journal of Psychiatry 55 (Suppl 2): S182–86. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5545.105524.

Reagan, Trudy Myrrh. 2007. ‘The Study of Patterns Is Profound’. Leonardo 40 (3): 263–69. https://doi.org/10.1162/leon.2007.40.3.263.

‘Religious Ritual in a Scientific Space: Festival Participation and the Integration of Outsiders - Robert M. Geraci, 2018’. n.d. Accessed 21 February 2019. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0162243918820428.

Sahani, Aroon. 2019. Bhava Spandana Interview by Ankita Anand . In person. London, UK.

Samuel, Geoffrey. 2008. The Origins of Yoga and Tantra: Indic Religions to the Thirteenth Century. Cambridge, UK ; New York: Cambridge University Press.

Timothy Morton. 2011. ‘Here Comes Everything: The Promise of Object-Oriented Ontology’. Qui Parle 19 (2): 163. https://doi.org/10.5250/quiparle.19.2.0163.

Vasudev, Jaggi. 2016. Inner Engineering: A Yogi’s Guide to Joy. First Edition. New York: Spiegel & Grau.