Technological Hauntology: Internalising the Spectre

“the 21st Century is oppressed by a crushing sense of finitude and exhaustion. It doesn’t feel like the future. Or, alternatively, it doesn’t feel as if the 21st Century has started yet. We remain trapped in the 20th century” (Fisher, 2010)

produced by: Benjamin Sammon

Hauntology

The practice of music recording has been with us since the invention of the phonograph which Edison originally created to posthumously preserve the voices of the deceased. These spectres of recorded musicians inhabit the temporality of time both "present and absent" (Reynolds, 2011). Hauntology fittingly plays on the ontological “being” and exchanges it for a being at a point of non-origin. The very construct of being is haunted hence the portmanteau hauntology. Jacques Derrida came up with this term in his book Specters of Marx so the relevance was not lost on him. Even more so, the word hauntology is pronounced the same as ontology in his native language French, so even the word itself is haunting.

This term would later be adopted by a series of critical theorists and music critics, most notably Mark Fisher and Simon Reynolds. Their interpretation of the term had special relevance when it came to music in the UK. The idea that the Americanisation of British culture in the 1980’s and the fall of the Soviet Union towards the end of the decade caused what Fisher refers to as “capitalist realism”. This would engulf society for the indefinite future. Put more eloquently in a quote that is attributed to Fredrick Jameson, “it is easier to imagine an end to the world than an end to capitalism” (Fisher, 2009). This void of imagination has created a cultural chasm of unimagined futures allowing a throwback culture to thrive, where creating anachronistic work seems the only means of expression. I remember hearing this predominantly at the height of the indie boom in the mid 2000’s. There was the post-punk revival, garage rock revival, even nu-rave which was a hybrid revival of rave music from the 1990’s and 1980’s new wave. This saturation of the present with the past causes a temporality where “time is out of joint” (Fisher, 2013).

Hauntology however is something different, it doesn’t just create throwbacks it emphasises the sound of a lost future that was never fully realised. This brings us back to the point of non-origin. Presently, we are at a disjuncture where we are unable to imagine the future, so we look back at other possible futures that could have been. For instance, artists like Belbury Poly and The Advisory Circle create a world in which the “Radiophonic Workshop were more important than The Beatles.” (Fisher, 2010).

The BBC Radiophonic Workshop (figure 1) has an important part to play in hauntology, setup in the early 1960’s to create theme music for radio and television shows, the Workshop was an environment of unbridled experimentation and creative excellence. At the vanguard of electronic music, the Workshop had to record sounds to tape, spending hours if not days cutting out individual notes at precise measurements to stick together making the entirety of a song. I found this labour-intensive form of creativity inspirational and have incorporated it into my own work. There is a meditative quality to laborious processes that I find appealing.

Technology

The more I observed consumer culture and its auto-cannibalistic nature, the more my focus moved towards technology. Since the dawn of music recording, new technology has emerged every few years which overtakes the previous incarnation in terms of quality, cost, portability and convenience. We can see this in recent years with portable music devices changing from cassette players to CD players to MP3 players within the space of a decade. This made me think about the anachronisms in music and film and how technology cannot really be anachronistic as, by nature, it evolves and does not return. There are exceptions to this for instance, vinyl records and reel-to-reel tape are formats that have recently resurfaced. In 2018 vinyl album sales grew by 15% (Caulfield, 2019) and the company Ballfinger have begun to manufacture a new line of reel-to-reel tape machines that haven’t been in circulation for decades (Nicola, 2018). in a world where physical formats are dying it is interesting to note that these markets appear to be re-emerging.

Such a resurgence could be partially stimulated by artists such as composer and musician William Basinski and his album The Disintegration Loops. This album uses deteriorating tape loops which were left to play for extended periods of time during the digitising process. This resulted in the gradual decay of each loop. It was an interesting concept album but also a study of the materiality of tape itself.

The materiality of tape has captivated musicians in recent years. Artists such as Amulets (figure 2) and Hainbach have been modifying cassette tapes and recorders to make interesting warping, analogue, ambient sounds. This harkens back to an obsession with old technology displaying characteristics of deterioration, most of which cannot be found in modern digital technology. As Kim Cascone would say, they are seeking the “aesthetics of failure”.

Interestingly enough, in his paper of the same name, THE AESTHETICS OF FAILURE: 'Post-Digital' Tendencies in Contemporary Computer Music Cascone talks about the complex and often intricate ways in which modern electronic musicians try to capture technological failure in digital technologies. Most of these artists use a digital method called granular synthesis.

Developed as early as the 1970’s by Iannis Xenakis, granular synthesis uses microsound technology which divides audio samples up into thousands of tiny grains which can be manipulated in various ways. This includes time stretching and reversing, with the ability to rearrange the grains and change each grains pitch (Roads, 2001). These developments were popularised in the 2000’s when consumer technology became advanced enough for musicians to be able to afford the necessary hardware.

“Later, closer to us but according to the same genealogy, in the nocturnal noise of its concatenation, the rumbling sound of ghosts chained to ghosts”

(Derrida, 1994)

Aims

This project is an exploration of the idea of a technological haunting, the computational process haunted by cassette tape, as the tape further degrades from overuse granular synthesis will time stretch the recording until there is just the remnants of the damaged tape under an auditory microscope.

This experiment involves recording back and forth between a cassette recorder and computer using granular synthesis with reverb. Every iteration of a cassette recording the sounds will be degraded and every iteration of granular synthesis the audio will be time stretched and restored. This will act as a dialogue between the late and current technologies.

Recording cassette tape and outputting audio results from granular synthesis happens in real-time so it can take many hours to create a large number of iterations. This seemingly dead time, that would usually be wasted in a normal sound recording environment, will be used to meditate on the process itself. I will be analysing my results, as I iterate, through a hauntological lens. More specifically, I will focus on the idea of a technological spectre whilst commenting on its cultural and philosophical significance. The laborious nature of the production resembles that of the way the Radiophonic Workshop to produce music and I believe this process both allows you to experience the materiality of the productions, hearing the sounds of the cassette’s mechanics spinning over the tape head and the humming of the computer fan, and reflect on the metaphysical aspects of real-time processing and time stretching.

I will also be using postphenomenology to deconstruct the hermeneutic relations that are created when we interpret the world around us using technology and how that differs between cassette and granularization. The importance of the postphenomenological approach is that it combines empiricism with philosophical analysis. This technological mediation enables us to analyse the worlds objectivity with our own subjectivity. (Rosenberger and Verbeek, 2015)

Tools

For these experiments I will be using a Sony Cassette-corder TCM-939, originally released in 1995, this was a common cassette recorder used in schools and universities at the time.

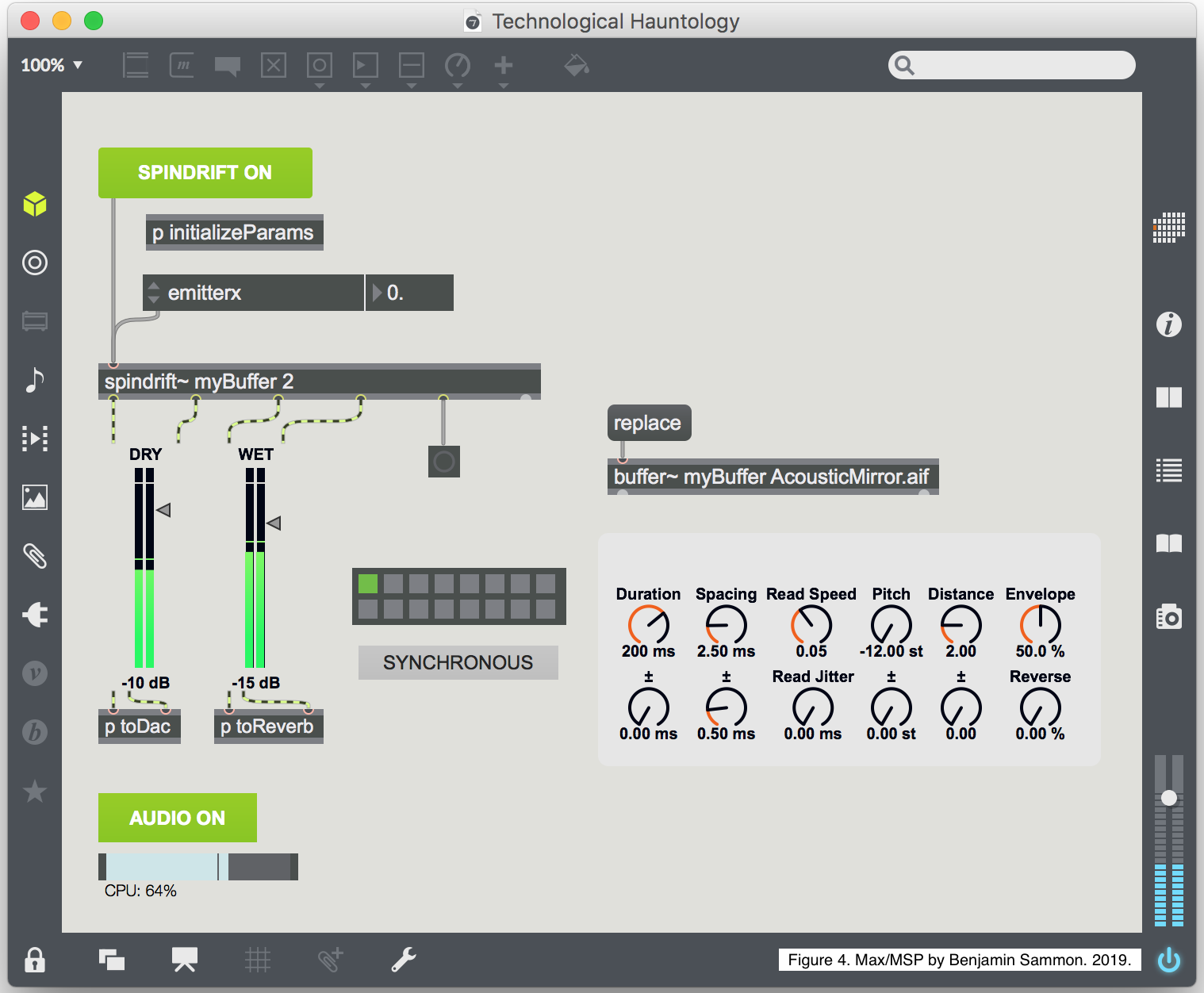

Secondly, I will be using Max/MSP, which is a visual programming language made predominantly for music and multimedia production. Along with a granular synthesis Max external called Spindrift~ which will allow me to experiment with granular synthesis with very low CPU overhead. (Norris, 2016)

“phenomenological ‘psychology’ is like any new science. It must look again and again at the phenomenon before it reveals its secrets.”

(Ihde, 1976)

Process

I wanted to remove myself from the musicality of the piece and become a technologist to make objective observations and avoid certain creative choices. this gives the spectre a voice to speak for itself. A significant part of performing music is embodiment, I wanted to disembody myself from the process to let the spectre take control.

Not unlike the way rock musicians traditionally use amplification to distort and abstract their guitar and vocal sounds the cassette distorts and obscures the recorded sound (Ihde, 1976). The degradation and saturation of the tape itself forms the core tonal qualities of the sounds. So much of what music is can be tied to the audio recording itself, in the article Metaphysics of Crackle Mark Fisher talks about how the only way we can access the prehistory of rock music is ‘through the haze of crackle’. This is significant as we are unable to imagine early rock’n’roll in any other way.

“From the perspective of the speculative realist, historical materialism risks not seeing the ontology and perspectives of objects – the essence in them.”

(Anderson et al. 2014)

Why Cassette Tape and Why Time?

As Ihde posits in Phenomenology of Sound “There is no neutrality to recording technology.” This is the case for all technology, everything has a predetermined agenda and the cassette tape is no exception. It has a lo-fi nostalgia that cannot be met by other mediums. The fetishization of its form goes beyond that of vinyl and reel-to-reel tape. Both vinyl and reel-to-reel have a high-fidelity quality which is closely matched to the resolution of high-end digital copies. Cassette does not so its popularity is due to its lo-fi tone.

This is perfectly exemplified by the music genre hypnogogic pop. Artists would record their music at home on 8 track tape mixers, most notably Ariel Pink who would crudely overdub instrumental parts, giving the recording its own timeless form inspired by the sound of 80’s pop songs recorded to cassette (Reynolds, 2011). James Ferraro speculates in reference to hypnogogic pop artists, as paraphrased by Reynolds in Retromania, “[while they fall asleep as toddlers in the 80’s] their parents played music in the living room and it came through the bedroom walls muffled and indistinct.”

Cassette tape has its own temporal quality too. There is no inherent philosophical value it’s material temporality, tape doesn’t know time, it is 85.73 meters of magnetic strip the 90 minutes of record time is of no significance. Through this medium we can experience other times, events and even imagined worlds but that is all irrelevant to its materiality. The material is full of poetics but ironically it is drowned out by the sounds that inhabit its magnetic memory.

This exploration is using materialities to reflect on itself from a speculative perspective, but it can be used to reflect on the world, “Audio culture is also about the changing materialities of recording, producing and sharing, and as such, CASSETTE MEMORIES is not only a yearning for the past, but also a reflection on the contemporary.” (Anderson et al., 2014) This “reflection on the contemporary” is a key component of sonic hauntology, “temporal disjuncture” created by a blurred contemporaneity is brought front and centre. The past is the present as the present consumes the past (Fisher, 2013).

The importance of time is clear in hauntology, it views time in a non-linear way, almost as if it has a fourth dimensional gaze. I see a clear connection between this and granular synthesis, both view time as porous and changeable. This is also the case for Ihdes work on music in phenomenology, the same music, “can be repeatedly played both temporally and spatially.” In this quote Ihde refers to music performance, you can play a song temporally different by slowing down the tempo. This in essence is the same as time stretching.

The idea of time stretching resonates with the human experience, time is malleable and indefinite. This is reflective of existence, even life itself has an undetermined length of time. I wanted to reflect this in my practice, cassette tape has a defined time but time stretching allows for infinite manipulation of that time.

“Modern tools let us view and manipulate the microsonic layers from which all acoustic phenomena emerge. Beyond these physical time scales, mathematics defines two ideal temporal boundaries the infinite and the infinitesimal”

(Roads, 2001)

The Acoustic Mirror

Whilst manipulating the grains in this piece, a quote by Jim Jupp came to mind, “It’s revisiting old textures and old imagined worlds with new tools” (Fisher, 2010). Using granular synthesis in this way I have effectively created a new textural world of exploration from an old one. This is technological hauntology at its prime; through technological means, creating new worlds with the past. When you hold up the acoustic mirror of the tape recorder it is always interesting to see what materialises (Ihde, 1976). This is also true for the digital mirror. The recursive nature of this experiment is revealing, every layer brings to surface new truths, the tonality, the noise, the artefacts of time stretching are doubled by the texture of the tape.

There are so many layers of reverb and tape grain that the spectre is barely recognisable except for the occasional industrial stab that bares a vague resemblance to the original sound. It is a ghost of itself, not an anachronism but something that is timeless and lives outside of “past” and “future”. The crackle gives the listener the illusion of space which the reverb widens. This goes back to Ihdes quote about music being played both “temporally and spatially”. The illusion of space helps with the illusion of time.

“The sample collage creates a musical event that never happened; a mixture of time-travel and seance.”

(Reynolds, 2011)

The Delian Mode

Delia Derbyshire is one of the most iconic and infamous musicians to come out of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, where she worked in the 1960’s and early 1970’s, her work has been sampled by artists including Danny Brown and Die Antwoord but she is most famously known for creating the original Dr Who theme tune.

In the hauntological tradition I wanted to create a piece that meditated on the Radiophonic Workshop so Derbyshire was an obvious choice. I decided to use her track Mattachin which I think perfectly incapsulates the whimsy and character of the Radiophonic Workshop. It is worth noting that this track along with many others made in the Radiophonic Workshop were created with melodies based in traditional folk music. This piece specifically creating a lost future of the medieval “Pavane” which was a form of dance music during the 16th century. This continued lineage is important in unravelling the tangential nature of hauntology.

All whimsy removed, the later iterations of this piece lend for a haunting listen. I could imagine hearing such sounds in a science fiction horror movie. With the character of the original track lost this spectre brings out the worst in the piece. Sounds that were originally wood blocks hit against each other now sound like a phantom slowly clawing at a steel silo, reverberating through and reflecting on the lost futures of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop. Conceptually, the imagined world in this piece is reminiscent of themes music on Burial’s self-titled debut album. Fisher describes it as follows, “the faded ten year-old tag of a kid whose Rave dreams have been crushed by a series of dead end jobs.” The realism of living in a society governed by late capitalism doesn’t allow much room for creativity. Not unlike the kid’s Rave dreams the Radiophonic Workshop was crushed due to cut backs at the BBC.

“There is no such thing as an empty space or an empty time. There is always something to see, something to hear. In fact, try as we may to make a silence, we cannot.”

(Cage, 1994)

Rearranging Silence

For my final experiment I was inspired by John Cage’s piece 4’33” which consists of no traditional music but made up of any ambient noise that would conventionally be considered as silence. Whilst recording this piece my cassette player malfunctioned so I decided to lean into the “aesthetics of failure” and utilise the malfunction as a part of the performance. I recorded the silence in my kitchen and every time the recorder stopped it would partially record the sound of the button pressed.

In this piece I rearranged the grains of and gradually slowed down the sample to 1/200th the speed. The final iteration really exposes the materiality of the cassette, the noise is slowed down to the extent that you can hear the individual grains rolling over the tape head. This made me think of a quote by Mark Fisher in Ghosts of my Life, “MP3 files remain material, of course, but their materiality is occulted from us by contrast with the tactile materiality of vinyl records”. The granularization of the sound has occulted the tape recording by “mending” it but as Derrida says in the film Ghost Dance “true mourning is internalising the deceased” which is the main focus of my technological haunting; the computational elements of the artefact are haunted by the analogue and simultaneously the computational is mourning by physically internalising the analogue.

Conclusion

Gradually the spectre materialises, it haunts until the sound is indistinguishable from the original source. You can hear a steady materialisation of the tape saturation slowly taking form and coating the sound in an analogue texture which is met by the exposure from time stretching and a sea of ethereal reverb. As Jim Jupp says, “The recording of space, real reverb/room sound and the virtual space on the hard drive. Like different dimensions” (Fisher, 2010).

Similarities can be made to the music by producer James Kirby also known as The Caretaker. Inspired by the haunted ballroom scene in the Stanley Kubrick film The Shining, Kirby utilized samples from old ballroom songs, dowsing them in reverb, as his first album suggests, to create Selected Memories From The Haunted Ballroom. The “future” in Kirby’s work is the post-processing which creates a digital space in which the ballroom music haunts. This is not dissimilar to my piece, but the digital is furthered with advanced computation.

The saturation of the sound created by the repeated recording on tape is analogous to the hauntological idea of the present’s saturation with the past. Rather than a cultural phenomenon it is a physical manifestation.

We can see in modern culture our current societal obsession with nostalgia, whether it is the Star Wars sequels, Stranger Things or genres of music like vaporwave. Vaporwave, as an example, commodifies 80’s culture, in most cases barely adding anything new, just repackaging it with a new glossy cover. It feels like “the dissolution of civilisation wrought by capitalism” has accelerated rather than destroyed it (Tanner, 2016). We are unhappy with the outcome of late capitalism but the only way we feel we can overcome this sadness is by inadvertently furthering capitalisms agenda. It forms a symbiotic relationship with culture sucking the life out of it like a vampiric spectre. Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi talks about the “slow cancellation of the future” (Fisher, 2013), what does the end of the future look like? Is it when capitalism finally cannibalises itself?

In his blog post about hauntology Adam Harper ponders “Hauntological art leaves us wanting to ask a highly important question of idealism: is Utopia dead or alive?” (Harper, 2009) the answer to this question is unclear, the creativity that hauntology affords is a positive step forward but the techniques and motivations are usually from a negative source. I do not feel we can find our lost future by searching in the past, we just have to live it and hope for the better future we seek.

Annotated Bibliography

Fisher, Mark. Ghosts of My Life: Writings on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Futures, Zero Books. 2013.

This book by Fisher is an amalgamation of his writings on (as the title suggests) depression, hauntology and lost futures. Much of the book is compiled of opinion pieces by Fisher himself, including several extracts from his infamous K-Punk blog. This also includes interviews with musicians, film makers and artists. The book is a critical deconstruction of many art forms, mainly focusing on music but also analysing film and television in great detail. He notably mentions political climates, philosophical theory and psychoanalysis as his main mediums of analysis of these works.

The focus of this book is largely hauntology, with attention paid to the cultural phenomena that lead to its occurrence. This includes an in-depth analysis of numerous musical artists, varying from The BBC Radiophonic Workshop inspired Belbury Poly and The Focus Group to contemporary artists such as Burial, James Blake and Drake.

Fisher’s critical dissection of these artists will act as a guide for me to dissect my own artefact. His approach to looking at the spectre in music and it’s channelling of lost futures will provides a clear theoretical framework of analysis to work to.

Reynolds, Simon. “Ghosts of Futures Past Sampling, Hauntology and Mash-Ups.” Retromania: Pop Culture's Addiction to its Own Past, Faber and Faber inc., 2011, pp. 311-361.

This chapter of Reynolds’ book offers a journalistic deconstruction and insight into sample culture. It is a witty and informative read with a wide range of critical approaches taken to discuss music, including cultural, technological, political and philosophical.

In this piece Reynolds talks about technology, such as Edison creating the phonograph, Basinski’s tape destruction experiments in “The Disintegration Loops” and the stylistic tape recordings of hypnogogic pop. He explores the cultural and historical significance of sampling and a myriad of its different iterations including hip-hop, plunderphonics and rave music. As well as using anecdotal personal accounts, he uses critical theory from the likes of Jacques Derrida, Karl Marx, Sigmund Freud. With all this in mind Reynolds provides a comprehensive deconstruction of sample culture.

I would like to use some of the text from this piece as commentary and analysis for my project, for instance, “Edison originally envisaged the phonograph primarily as a means of preserving the voices of loved ones after death.” Would be a fitting quote for the way I would like to preserve the materiality of cassette tape after it’s obsolescence. Also, as one of the foremost writings on hauntology I would like to use this chapter to help me define hauntology in my thesis.

Cascone, Kim. “The Aesthetics of Failure: 'Post-Digital' Tendencies in Contemporary Computer Music.” Computer Music Journal, vol. 24, no. 4, Winter 2002, MIT Press. 2002, pp. 392-398.

As a microsounds composer and digital sound artist who has worked with the likes of Thomas Dolby and David Lynch, Cascone’s paper offers a valuable analysis of the post-digital aesthetic. He gives an effective insight into the technologies and approaches used by the artists involved in the movement including quotes from well-respected musical theorists such as Don Ihde, Curtis Roads and John Cage.

This piece explores the importance of technological failure as a medium for music creation. Spanning a wide array of musical styles and genres including a variety of techniques such as glitch, granular synthesis, noise and much more. It goes into detail about how different musicians throughout the world have applied these techniques in unique ways of music making.

I plan to apply some of the techniques referenced in this paper to my own practice in pursuit of creating my final artefact. With the aesthetic of failure in mind and using microsound technology, I will focus in on the intricacies of cassette tape. I will also be using some of the technologies referenced, including Max/MSP and Pure Data.

References

Andersen, C., Pold, S. and Riis, M. 2014. A Dialogue on Cassette Tapes and their Memories.ARPJA. http://www.aprja.net/a-dialogue-on-cassette-tapes-and-their-memories/

Cage, J. 1994. Silence: Lectures and Writings. Marion Boyars; New edition edition.

Cascone, K. 2002. THE AESTHETICS OF FAILURE: 'Post-Digital' Tendencies in Contemporary Computer Music. Computer Music Journal 24:4 Winter 2002 (MIT Press).

Caulfield, K. 1st December 2019. U.S. Vinyl Album Sales Grew 15% in 2018, Led by the Beatles, Pink Floyd, David Bowie & Panic! at the Disco. Billboard. https://www.billboard.com/articles/columns/chart-beat/8493256/vinyl-album-sales-growth-2018-beatles-david-bowie-pink-floyd

Derrida, J. 1994. Specters of Marx. Chapter 1: Injunctions of Marx. Routledge.

Fisher, M. 2009. Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative?. Zero Books.

Fisher, M. 2010. The Metaphysics of Crackle: Afrofuturism and Hauntology. Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture 5(2): 42–55. https://dj.dancecult.net/index.php/dancecult/article/viewFile/378/391

Fisher, M. 2013. Ghosts of My Life: Writings on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Futures. Zero Books.

Harper, A. 2009. Hauntology: The Past Inside The Present. http://rougesfoam.blogspot.com/2009/10/hauntology-past-inside-present.html

Idhe, D. 1976. Listening and Voice: A Phenomenologies of Sound. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press.

Nicola, S. 8 May 2018. The Ultimate Analog Music Is Back. Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-05-08/the-ultimate-analog-music-is-back-ballfinger-reel-to-reel-tape

Norris, M. 2016. spindrift~ granular synthesis Max external. http://www.michaelnorris.info/software/spindrift

Reynolds, S. 2011. Retromania: Pop Culture's Addiction to its Own Past. Chapter 10: GHOSTS OF FUTURES PAST Sampling, Hauntology and Mash-Ups. Faber and Faber, inc.

Roads, C. 2001. Microsound. MIT Press. London, England

Rosenberger, R and Verbeek, P. 2015. Postphenomenological Investigations: Essays on Human–Technology Relations (Postphenomenology and the Philosophy of Technology). Lexington Books.

Tanner, G. 2016. Babbling Corpse: Vaporwave and the Commodification of Ghosts. Zero Books.

Unkown. Accessed May 1st 2019. Mattachin. https://wiki.delia-derbyshire.net/wiki/Mattachin

Film

Blake, K. 2009. The Delian Mode: Delia Derbyshire Documentary. Philtre Films.

Kubrick, S. 1980. The Shining. Warner Bros.

McMullen, K. 1983. Ghost Dance. Channel Four Films, Looseyard Productions, ZDF. West Germany/UK.

Spice, A. 2014. Pioneers Of Sound: The story of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop. Vinyl Factory Films. London. https://thevinylfactory.com/films/pioneers-of-sound-documentary-bbc-radiophonic-workshop/

Music

Basinski, W. 2002. The Disintegration Loops. 2062 (label).

Burial. 2006. Burial. Hyperdub.

Cage, J. 1952. 4’33”.

Derbyshire, D. 1963. Doctor Who theme music. BBC Radiophonic Workshop.

Derbyshire, D. 1984. Mattachin. BBC Worldwide Music.

The Caretaker. 1999. Selected Memories From The Haunted Ballroom. V/Vm Test Records.

Also mentioned:

Amulets – http://www.amuletsmusic.com/

Hainbach – https://www.hainbachmusik.com/

Audio Sources

“The Acoustic Mirror” is based on the opening music to This episode of Andy Pandy from 1952 - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XuPVcxzVD5A

“The Delian Mode” is based on the song Mattachin which can be found here - https://www.bbc.co.uk/music/artists/39f0d457-37ba-43b9-b0a9-05214bae5d97