Snowflake Generation

Julian Burgess

Computational Arts-Based Research and Theory (2018-19)

Goldsmiths University

Introduction

While researching for my end of term project I came upon Twitter’s blog post announcing the creation of an algorithm called Snowflake, used to generate a unique ID for each tweet. I was interested and so began to look into how the algorithm worked. I kept thinking about the word snowflake and the recent rise of its use as a pejorative term, as a label for a generation of people, and its underlying usage as a metaphor for uniqueness. In this paper, I am going to investigate the materiality and semiotics of snowflakes and uniqueness and look at generative artworks involving snowflakes. I will use this exploration as a basis for creating my own generative snowflake artwork.

Physical phenomena

In nature

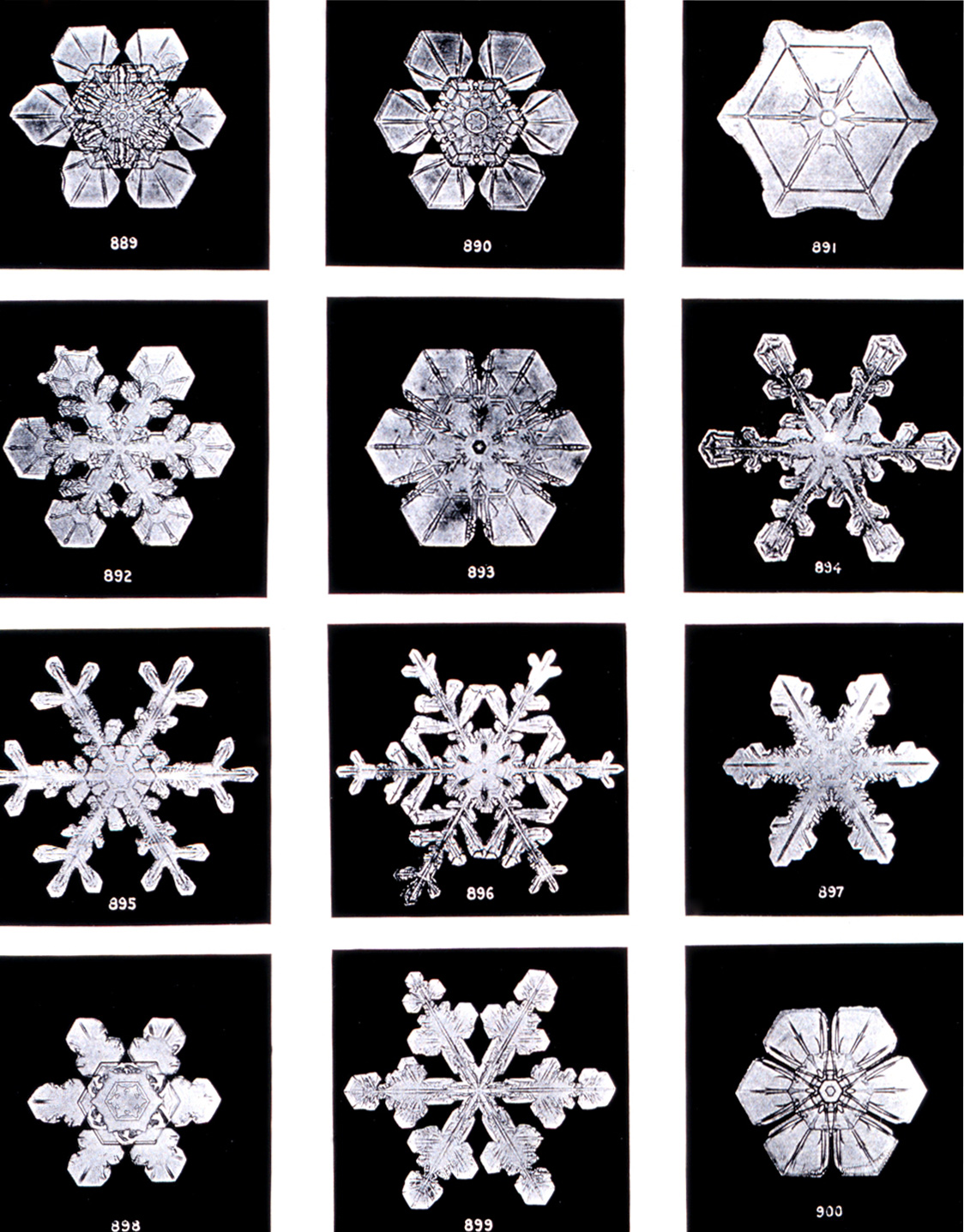

Bentley, Wilson A. Studies among the snow crystals during the winter of 1901-2

The adage that no two snowflakes are alike is often used as a way to illustrate the huge degree of variety that exists within the natural physical environment. A large snowflake can be observed with the naked eye to be a complex and intriguing shape.

“I do not believe that even in a snowflake this ordered pattern exists at random” — Johannes Kepler, 1611

Kepler noted the regular six-fold symmetry of snowflakes, taking it as evidence of the supreme reason from the creator’s design. The phenomena of their uniqueness were first truly captured in 1885 by Wilson Bentley when he developed a photomicrography technique to take photos of individual snowflakes. He went on to take over five thousand such images, producing various publications of them[1].

Scientific research indicates that this idea of uniqueness is almost certainly correct, at least once snowflakes have developed beyond tiny crystals[2]. Indeed we can consider snowflakes to be a paradigm of uniqueness [3] so apt is the metaphor that it seems unlikely something else could replace it.

The uniqueness of a snowflake comes from the way in which it is formed in the upper atmosphere where tiny variations in temperature and humidity affect its growth and ultimate shape. If we follow this thread a little further we can think about the structure of water molecules which form the snowflakes, comprised of two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen (the electron bonds are what cause the snowflakes have six-fold symmetry often with a hexagonal shape), a step further and we look can look at a single hydrogen atom with its single electron shell. In some sense we are problematising the concept of uniqueness, each atom is distinct and cannot become anything else, but at the same time they are also uniform and distinguishing one from another pushes the limits of our cosmic understanding. In a final step if we rewind time to the Big Bang then all matter and energy are reduced to a singularity, the concept of uniqueness is moot. We can think of all future uniqueness as unwinding in a thread in time from this point spiralling outwards.

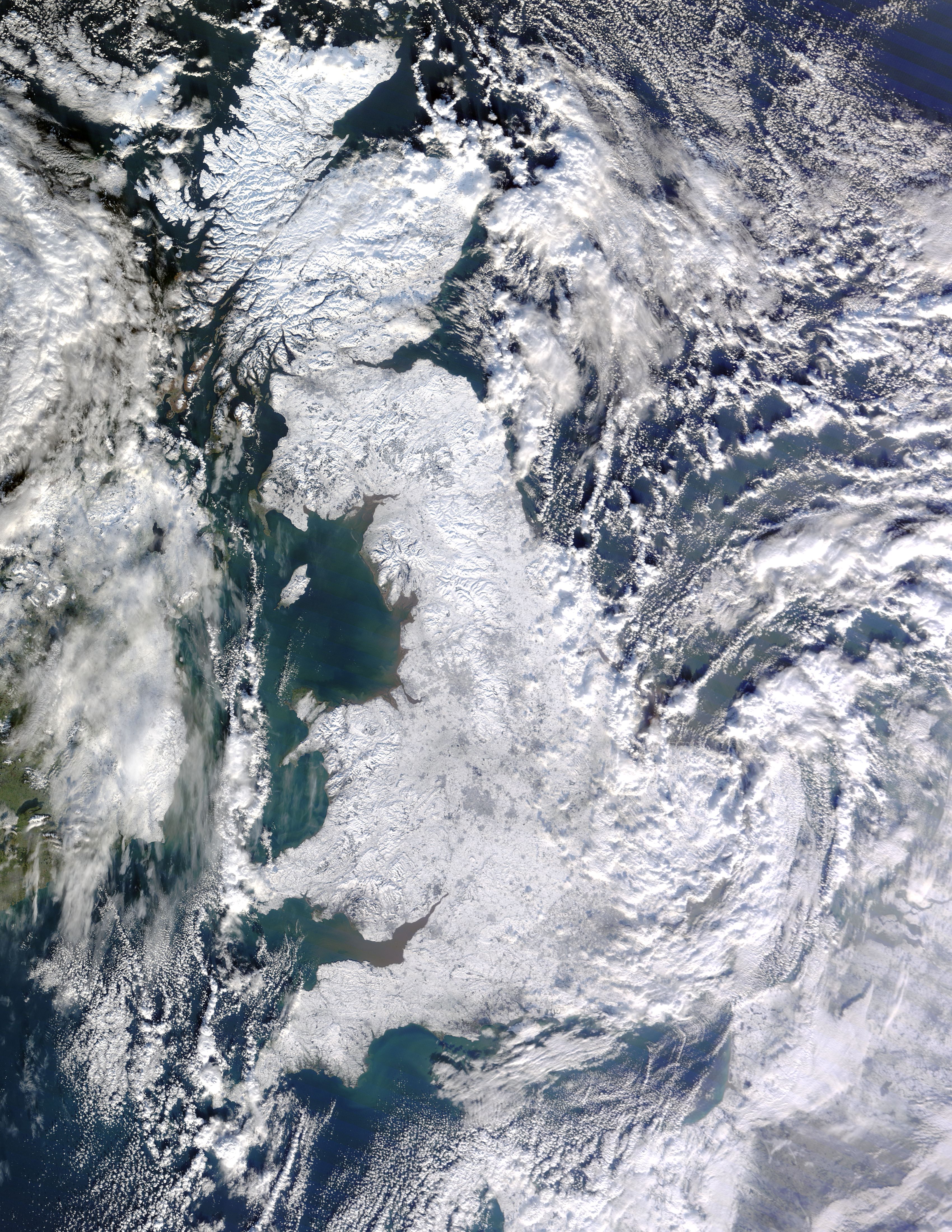

Satellite image of snow-covered Great Britain on 7 January 2010, taken by MODIS on NASA's Terra satellite.

Let us consider this photo of the United Kingdom, blanketed by heavy snowfall in January 2010, and try to think of the number of individual snowflakes which collectively form such a scene. Now instead of scaling the snowflakes up as to be visible as in Bentley’s photomicrography, we scale in the other direction. This leads to another, almost paradoxical aspect of uniqueness when scaled to both a vast number and tiny size, that the individuality can be lost and we see different materiality appear. A blank of pure white snow has a uniform surface topology, and yet beneath a microscope, it yields a different surface of endless individuality. I wanted to capture the essence of this seeming contradiction in my artwork, for it to have this dual aspect relationship of uniformity at a distance and uniqueness in proximity.

In art

In art, uniqueness has an interesting relationality. Famous artworks are often copied both by other artists and as souvenirs, but usually, the copying begins earlier with the artist themselves producing sketches and maquettes to shape the idea. >The piece itself is in a state of relational flux between concept and concrete with the artist as mediator.For physical work, the piece materially changes over time, as paint and varnish age, and even how the piece is hung in which frame and against what background. All of these contextual elements add to the uniqueness of a work in terms of how one experiences it. In The System of Objects (Baudrillard) says:

“a luxury car is in a red described as 'unique'. What 'unique' implies here is not simply that this red can be found nowhere else, but also that it is one with the car's other attributes: the red is not an 'extra'.”

Mass produced woodblock and screen prints always have tiny differences in offsettings, inks and pigments exist making each one unique. However, when we use the word unique in this context we would usually mean differences which would be clearly discernible to the naked eye (or perhaps another sense such as audio differences). Such minute variations might be considered a distinction without a difference. Where should the line be drawn? Our journey through the physical world shows there is no obvious point and that it’s purely the subjective concern of the artist. We should also consider what constitutes a work of art which we can individuate.

In The Uniqueness of a Work of Art (Meager, R 1958) the differences between Michelangelo's David and Milton’s Paradise Lost are considered as spatiotemporal works. What constitutes a poem? The first written form, a printed copy, a recitation or a recording of a reading by the author? Through this lens, we can now also re-evaluate the statue as work which is under a slow but constant change both in how it is viewed and the context and location in which it exists, but also the physical changes from pollution, restoration. In this way, we can consider any work to be a series of manifestations.

“a copy of David provided it is a good one and produced by hand, is also a work of art” — Meager, 1958

Many works play on the idea of uniqueness and uniformity. I was drawn to Ai Weiwei’s Sunflower Seeds (2010) which features around one hundred million hand-painted porcelain sunflower seeds, each appearing both identical and unique[4]. Up close you see the unique identity of each seed, at the middle distance you see them as collection, and the sensorial experience of the sounds of walking on them (when permitted) becomes eminent. The view from a distance is a uniform textural topology, where the colour becomes the dominant feature and the shadows and highlights formed from the perturbations in the topology.

Specialness is perhaps more appropriate to think of as a relationship, as we think of the person or item as special relative to a group, and the relationship to the group and within the group defines the hierarchical value of these relations. This relationality is, of course, temporal as a thing’s specialness waxes and wanes with the zeitgeist of the day more from the ravages of time itself upon the nature of the thing.

In language

While the use of snowflake as a metaphor for uniqueness dates back to Bentley’s photographs, a new usage appeared in 1983 where it is used to identify a person, as having a unique personality [5]. This usage was in turn mocked in Fight Club (Palahniuk, 1996) where the anti-protagonist Tyler Durdan states during a scene initiating new members to the club.

“You are not a beautiful and unique snowflake. You are the same decaying organic matter as everyone, and we are all part of the same compost pile.” — Fight Club, 1996

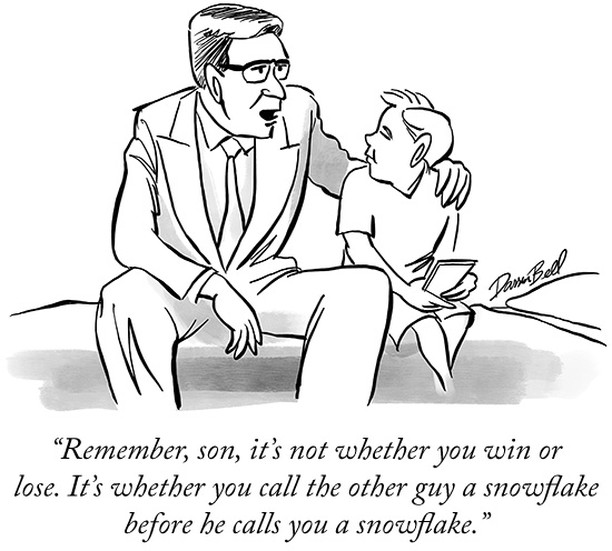

Since then the term has changed again and has become a pejorative term for a person seen as overly sensitive or easily offended. The original notion of a snowflake’s uniqueness has been displaced by allusion to its fragility[6].

As an insult it is effective, a broad way of criticising someone for being too sensitive and in turn claiming your own self-toughness. It’s an idea that is broad-ranging, easy to remember and has spread widely, especially amongst the alt-right.

The New Yorker, April 2019

instagram.com/p/BwpInaGD__Q/

Twitter’s snowflake algorithm

Within the digital realm, uniqueness is much easier to discern since all information is represented as binary. If the boundary is agreed then bitwise comparison will reveal if two items are identical. This also gives rise to the notion that within a bounded digital topology only a finite number of unique states are possible within this mimesis of nature.

This extends to any type of coded information, even natural forms such as DNA. Here we find that unique is actually not common at all, since even identical twins have subtly different DNA. Even when items are directly cloned, the organisms continue in the vitality on different paths. This effect was effectively demonstrated in One Trees by Natalie Jeremijenko, where one thousand Paradox Walnut trees were cloned and planted in pairs around the San Francisco Bay Area. Despite all being genetically identical the trees grew and lived and died in quite different ways.

Twitter launched in 2007 and first gained popularity at the SXSW conference. The number of tweets per day grew from around 5000 per day in 2007 to 300,000 a year later and to 50 million by 2010. The rapid growth meant that Twitter had a lot of problems scaling their service to work consistently and the “fail whale”, an image which appeared on the error page, became almost as well known as their iconic bird logo[7].

The snowflake algorithm was created to solve the problem of efficiently creating unique IDs across different servers running in different geographic locations where they would at times lose contact with each other (network partition)[8].

I emailed Ryan King, one of the lead developers at the time to confirm if the origins of the algorithm’s name was due to the service ensuring each ID being unique whilst formed independently. He responded:

“kYup, that was it. not much more complicated than that other than that there was a preexisting, related project called ‘snow goose’. Called such because it was a migration project.”

To give a brief forensic analysis of Twitter’s snowflake we have 64 bits in total which breaks down as 41 bits for millisecond precision from Twitter’s custom epoch (gives 69 years worth of possible IDs), 10 bits to identify the server which generated the ID and 12 bits sequence to give a chronology for each ID generated within that millisecond. The first bit is unused since by convention that denotes a negative number.

So for Twitter, we have around 9.2×1018 possible IDs, approximate the same as the number of grains of sand on earth. However that the vast majority of these possible IDs will never be created due to how many servers are allocated and that they accounted for the capacity to be higher than expected usage. In this sense, the snowflake algorithm defines a latent temporal topographic realm of unique IDs to which tweets are attached.

If we take a look at the components parts of the anatomy above then we see that uniqueness is only guaranteed for the whole and that within the ID there are relationships which are formed. Many snowflakes will share the same server ID and when the service is popular then we can expect many will be created at the same millisecond. This practice has similarities to the work Serendipity created by Kyle McDonald[9] using Spotify data to show when two people somewhere in the world both played the same music track at the same time. Following this idea, we find the thing power of snowflake id. The algorithm has been created and the initial parameters set, but the creation of IDs within the latent space is manifested through and entangled with the survival of the body it serves (Twitter), or beyond since the algorithm was released under an Open Source language, this vitality can spread and outlive its original host.

Serendipity (2014) — Kyle McDonnald

This leads me to think about the content of the Tweet, which so far I’ve ignored. At the time of the creation of the snowflake algorithm, a Tweet was limited to 140 characters (it’s presently 280 characters). The latent topology for content of what could be tweeted is far greater than the space of the snowflake IDs, meaning that the content of each tweet could be unique, however in practice we don’t just tweet random assortments of letters (or at least not all the time), so we can actually expect that many tweets with identical content do exist, excluding retweets which is a practice of doing exactly that.

Computational Art

In my artwork, I wanted to visualise the relationship between the underlying digital topology of the Twitter snowflake IDs and the materiality of Bentley’s photomicrography. I wanted the work to present at both micro and macro scale, showing each ID as a unique snowflake pattern which is hyper-programmably generative and can be called to produce output for any given ID, disintermediating the content and Twitter itself. Then by producing the output for many IDs, I would hope to get the blanket uniformity of where the details meld away and we see the work as a blanket of snowflakes.

I decided to create snowflake patterns using a Lindenmayer system (L-System), a simple recursive coding system which can be translated into pen tool movement commands. I started with the Koch snowflake[10] which is a fractal. I then adapted it to add high-level complexity which also removes the fractal nature since it is no longer self-similar although it can be iterated to unlimited degree.

I added multiple terms to my snowflake code that allowed me to change its appearance by varying the length of different segments. These can then be tied to the anatomic parts of the snowflake ID that I outlined earlier. I wanted to look at using the geographic server ID component to surface a psychogeographic linking the locations of the servers, as opposed to the location of the user who sent the tweet. Producing the complete algorithm is complex since the latent space is so large (63 bits). I would particularly like to look at the ordering since there will be many snowflakes that are superficially similar, it would be good if they aren’t clustered together.

I initially concentrated on plotting snowflakes using my obsolete Roland DPX-3300 plotter which I have reanimated by writing software to bridge compatibility with the HTML5 Canvas API. Using the plotter is also interesting since a reasonable degree of randomness creeps in from the nature of the pen on paper, minute bumps and grit on the paper.

Snowflake (2019) — Julian Burgess

I later found time to laser cut a single one of my generated snowflakes into clear acrylic. I really like this aesthetic as it gives a slight impression of them being made of ice and the idea of temporality in their composition through the changing structure of the refracted light. Ideally, I would like to laser cut a much larger number into bigger sheets of acrylic so I could get the micro and macro scale which I talked about earlier, however it has been tricky to balance the time with my job commitments.

Conclusion

Snowflakes are an apt metaphor for uniqueness, perhaps the perfect one. However, defining uniqueness in a physical sense is a slippery slope since we can continually reduce the object to component parts and it becomes problematic to find a boundary.

In the digital domain, we can easily define binary equality between entities, much software relies on this mechanism. We have a tightly defined binary topology from which all digital media grows. We can also create things which are indistinguishable to humans but wildly different in the underlying digital domain. In this a simplified universe that we can inspect down to the bit, the lowest conceptual level. As the physical construction of computers has developed this milieu is hidden in increasingly tiny electronic components and data is strewn in an entanglement across many layers of hardware and distant networked devices in the real world all working to support our parallel cyberspace.

In an artistic context, uniqueness is perhaps impossible to consider outside of conceptual space. All works are transient and subject to change in their surroundings an interpretation, which change their relationships to other works and the degree of similarity. In that sense uniqueness really comes from the totality of the vast web of relationships stemming from the piece to the artist and to the viewer, the work is the unique focal point of these relationships and embodies them,

Annotated bibliography

Meager, R. “The Uniqueness of a Work of Art.” Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, vol. 59, 1958, pp. 49–70. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/4544604.

Meager considers what sort of thing an individual artwork must be how uniqueness can be evaluated. Although the work is written at the beginnings of postmodernist art movement it takes a philosophical approach as one would expect with the Aristotelian Society. It was of interest to me the approach of looking at the temporal nature of all works and figurations of work as copies. Looking at what can be considered original and a copy, where an artist repeatedly attempts the same work, and where another artists copies a work as a work in it’s own right. Setting a comparative framework only works if characteristics can be agreed upon which ultimately difficult.

Lin, Y and Vuillemot, R. Twitter Visualization Using Spirographs. Leonardo 2016 49:2, 170-172 https://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/abs/10.1162/LEON_a_01063

The piece describes the Spirograph, the mechanism and a brief history of how they are produced and why it’s structure leads to a unique signature of geometric shape outputs. The spiragram has been used before to create patterns similar to that of nature and in artworks such as Lauren Thorson’s “First 24 Hours of Spring”. In this work they selected three parameters to study how adjustments lead to outputs similar to various types of flower petal arrangements seen in nature. The output they produced is best seen as animation, but static images show the change in the rhythm of the conference for which they produced the artwork.

Cramer, Florian. Words Made Flesh: code, culture, imagination. Rotterdam: Piet Zwart Institute. 2005

Cramer looks at the origins of the idea of code as executable instructions, long before the invention of computers and considers the practices of music, magic and religion. Looking at the computer as a performer of commands that previously were the work of humans, including thinking processes. These instructions we give to computers are now in a formalised language inscribed in code. Symbols have cultural significance, and these work their way in the computer languages we create, forming persistent structures of within the code in how they mediate between human and machine.

References

- Kepler, Johannes. The Six-Cornered Snowflake. Oxford: Clarendon P, 1966. Print.

- Baudrillard, Jean. The System of Objects. London: Verso, 2005. Print.

- Palahniuk, C. (1996). Fight Club. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

- Bentley, Wilson A. Studies among the snow crystals during the winter of 1901-2 with additional data collected during previous winters and twenty-two half-tone plates," In Annual Summary of the Monthly Weather Review for 1902. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1903.

- Page, Mark, Jane Taylor, and Matt Blenkin. "Uniqueness in the forensic identification sciences—fact or fiction?." Forensic science international 206.1-3 (2011): 12-18.

-

Snowflake - https://github.com/twitter-archive/snowflake

https://developer.twitter.com/en/docs/basics/twitter-ids.html - https://www.wired.com/2012/12/algorithmic-snowflakes/

-

Theory of the Snowflake Plot and Its Relations to Higher-Order Analysis

Methods

- Leonardo

https://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/0899766053723041

Works consulted

- Gravner, Janko, and David Griffeath. "Modeling snow crystal growth II: A mesoscopic lattice map with plausible dynamics." Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena 237.3 (2008): 385-404.

- Rosenberger, Robert, and Peter-Paul Verbeek. Postphenomenological Investigations: Essays on Human-Technology Relations. Lanham: Lexington Books, 2015. Print.

- Da, Costa B, and Kavita Philip. Tactical Biopolitics: Art, Activism, and Technoscience. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 2008. Print.

- Stengers, Isabelle. “Thinking with Whitehead - a Free and Wild Creation of Concepts.” Thinking with Whitehead - a Free and Wild Creation of Concepts, Harvard University Press, 2014.

- Reconstructing Twitter's Firehose https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=19266823

- Sunderman, Vida. Tatted Snowflakes. Dover Publications, 2012. Internet resource.

- Paperfold snowflakes https://robbykraft.com/snowflakes/

-

Almond Darren, The Principle of Moments 2019 - artwork

https://www.studiointernational.com/index.php/darren-almond-the-principle-of-moments

[1] Bentley, Wilson A. "Studies among the snow crystals during the winter of 1901-2 with additional data collected during previous winters and twenty-two half-tone plates," In Annual Summary of the Monthly Weather Review for 1902. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1903.

[3] Page, Mark, Jane Taylor, and Matt Blenkin. "Uniqueness in the forensic identification sciences—fact or fiction?." Forensic science international 206.1-3 (2011): 12-18.

[4] https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-modern/exhibition/unilever-series/unilever-series-ai-weiwei-sunflower-seeds