Postcolonial Computing and Memory in Indigenous Australia

How are postcolonial computing and technology changing the archiving and dissemination of traditional knowledge and collective memory?

Written by: Elias Berkhout

Françoise Vergés, at the 2018 iteration of Transmediale, presented a keynote titled Politics of Forgetfulness, focusing on the propensity of the coloniser to forget their past. As an Australian, her presentation prompted me to consider how what she was discussing was relevant to a variety of projects and initiatives being explored by First Nations peoples across Australia. Specifically, projects which involve the pursuit of reclaiming their history, their stories, their traditional knowledge, and collective memory, through appropriating “colonising technologies” (Andrew, 2016) for their own means. Through my research since then I have found myself reading extensively on Indigenous Australia’s reclamation of the archive, through initiatives such as the Ara Irititja Project, which aims to explore strategies to create, maintain and contribute memories and knowledge to an archive in a culturally appropriate and respectful manner. Much discussion surrounding these topics focus on “the so-called ‘archival turn’… Inaugurated by Appropriation Art in the late 1970s and early 1980s” (Jorgensen & McLean, 2017), with reference to Foucault’s ‘power/knowledge’ and the writing of Derrida, for whom “archives enact a concealment rather than a revelation” (Jorgensen & McLean, 2017). I will also investigate other significant knowledge-dissemination tools: products of the current era of ubiquity, including Weerianna Street Media’s Welcome To Country and Virtual Songlines’ immersive VR and gaming experiences in pre-colonial settings of some of Australia’s major cities, both of which illustrate the ongoing transition towards more “out-of-the-box computing” (Ekman et al., 2016) with a focus on pre-colonial space and place. Finally, I will be exploring the creative, conceptual and computational aspects of works by artist Robert Andrew, who makes use of open source hardware and software as well as electromechanical componentry to make artworks which reveal themselves over days, weeks, even years, through both subtractive and additive methods, intended to deconstruct and erode Eurocentric narratives surrounding Indigenous history, memory and language. In spite of over two hundred years of enforced forgetting, I intend to explore how these projects are examples of many Indigenous groups and nations’ transition from an oral tradition of history and collective memory to digital systems which foreground and emphasise flexibility.

In recent years, discussions surrounding preservation have been paramount in academic and Indigenous circles. This has encompassed language, with researchers such as Professor Jakelin Troy and Uncle Stan Grant focusing on endangered languages in New South Wales, and many other elements of traditional knowledge. Since the arrival of smartphones in the late 2000s it has also included an influx of apps and other projects which make use of digital technology so as to allow information to travel further, more efficiently, and not restrict it to the specific communities for whom these works are “projects of cultural salvage” (Stoler, 2008, p. 198). This digital development has not been limited to Australia, and has been described by Joshua Sternfeld as digital historiography: “the interdisciplinary study of the interaction of digital technology with historical practice” (2011, p. 544). Where Sternfeld focuses on the necessary processes to maintain archival accuracy in such projects, in which the lines are blurred between “‘records’ and ‘documents’, and ‘archives’ [and] collections” (2011, p. 551), the Ara Irititja Project is focused on the digitisation and perpetual availability of artefacts which were previously removed by “visitors to the Ngaanyatjara, Pitjantjatjarra and Yankunytjatjara lands in Central Australia”, such as “photographs, film footage and sound recordings… some of [which] were filed away in the archives of public institutions, others were lost in family photo albums or packed away in old suitcases and boxes” (Ara Irititja Project, 2011). Ara Irititja – ‘stories from a long time ago’ – has been underway as a process of repatriation since 1994, but more than this, it “is all about responding to Anangu; holding digitised archival material alongside born digital recordings in culturally appropriate relationships, accessed through a sensible interface, easily searchable, and with results that hold meaning for Anangu” (Dallwitz et al., 2017, p. 250). Through collaboration with Anangu people on the development of the archive, how it is accessed and who can access what material, it has become an important touchstone in the conversation about “how information about [people] gets saved, who benefits from it in the future, and it grows and how peoples’ memories can be collected” (Dallwitz et al., 2017, p. 250). According to Derrida, as noted by Jorgensen and McLean in the preface to Indigenous Archives: The Making and Unmaking of Aboriginal Art (2017), “The Archive’s authority crucially depends on forgetting, upon a historical amnesia, and the power of the archival… signals the trauma that brought about the forgetting in the first place” (p. x). In the case of the Ara Irititja Project, and almost all other initiatives involving preservation of traditional knowledge in Australia, the aforementioned “forgetting” was enforced by the coloniser.

… the native population is increasing. What is to be the limit? Are we going to have a population of 1,000,000 blacks in the Commonwealth, or are we going to merge them into our white community and eventually forget that there ever were any aborigines in Australia? (Commonwealth of Australia, 1937, p. 11)

A digital archive is practical in myriad ways for such memory and preservation initiatives in Australia today. The digitisation of historical material, as well as the ability to contribute to the archive in a flexible and culturally appropriate manner allow us, and the communities for whom these archives exist, to “consider digital historical representations as active dynamic creations, rather than static objects” (Sternfeld, 2011, p. 552), a view similar to Derrida’s, that “the archive is never closed. It opens out of the future” (1995, p. 68). A demonstration of Ara Irititja by Janet Inyika elucidated “the live facility of Ara Irititja to record stories for these images” (Dallwitz et al., 2017, p. 253). In this case, a recording is made of Inyika speaking about the stories behind some photographs of her as a young girl which are available in the archive. The focus on flexibility often leads to foregrounding interaction via speaking (to add to the archive) and listening (to access information already stored in it). This logocentric approach enables the continuation of the oral tradition of knowledge sharing, and draws attention to Derrida’s criticism of society’s focus on and obsession with speech over writing. Ironically, it was this oral tradition, and the lack of written records which was used for centuries as a signifier of the inferiority of First Nations cultures. Ara Irititja’s contents can be “sorted into Open Access, Sensitive and Sorrow – this last category indicating that persons seen, heard or named in the files are recently deceased. There are also divisions between men’s and women’s materials, sacred and secular, and so on. This has resulted in a living archive that is response to the needs and concerns of present-day Anangu, frequently used, much loved and admired” (Dallwitz, et al., p. 266)

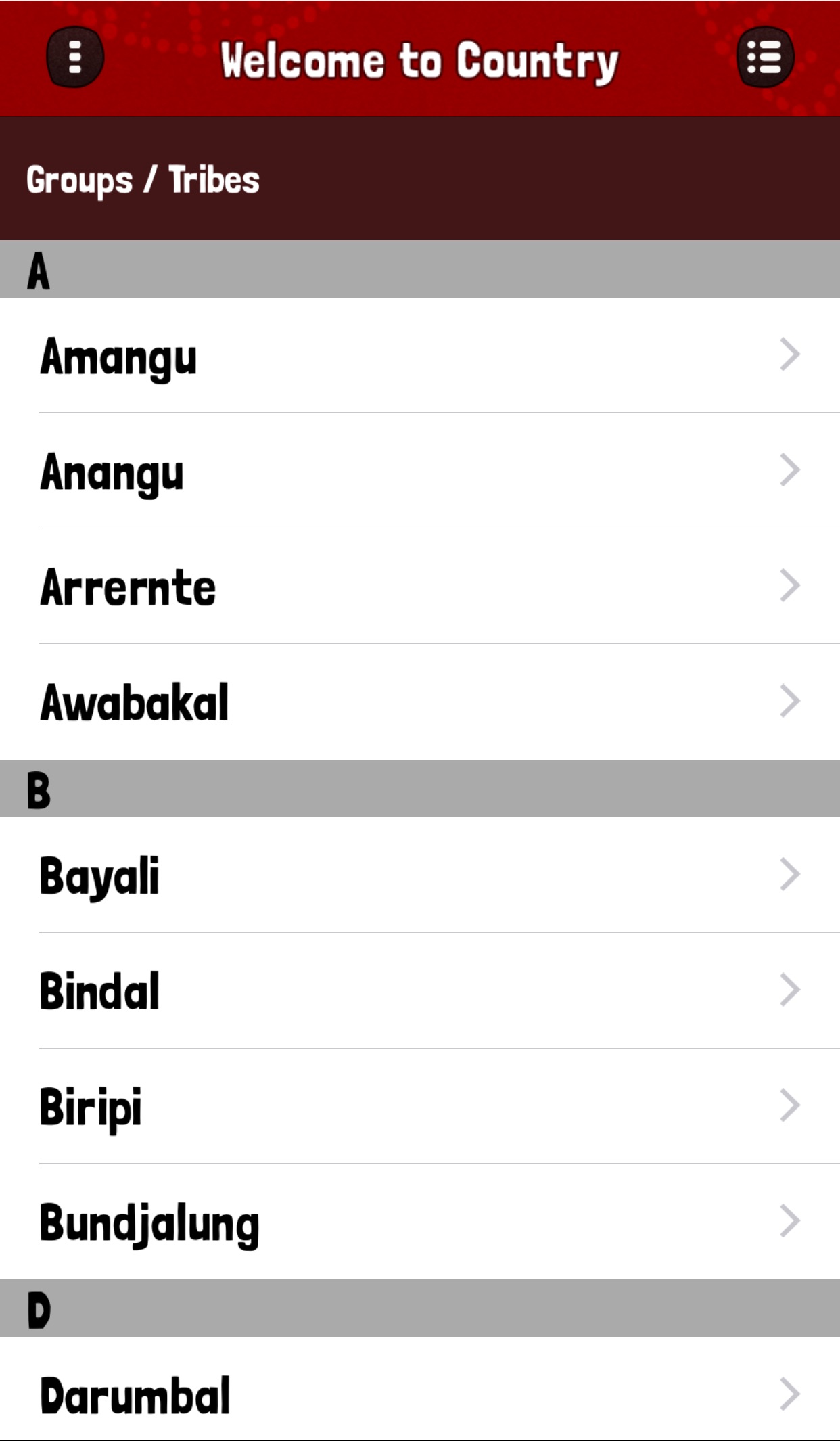

While projects such as Ara Irititja are crucial to the preservation of collective memory, other examples of digital historiography which are more outward looking and intended for a wider audience, both Indigenous and otherwise, are often available through the App Store. Apps can be “integrated with or embedded into everyday… activities” (Ekman, 2011), in the way that Welcome To Country is, where it utilises geolocation data from the user’s phone to notify them when they cross a tribal border onto neighbouring country, and, if available, provides a short video of a welcome to country by a traditional custodian of the land the user is on. Thirty five groups – out of over five hundred across the continent – are featured on the app as of early 2018, and Weerianna Street Media, the company behind the app, are working on expanding this. Although the app is intended to work invisibly and in the background, it is also a rewarding way to learn more about groups which may reside many thousands of kilometres from where the user is. Unfortunately, when I was in Sydney, Canberra and surrounding areas last year, I received no push notifications to tell me when I was moving across borders. Apps such as Welcome To Country as well as other similar “tools at our disposal, and those that have yet to be invented, promise enhanced capacity to ask new humanistic questions that would otherwise not be possible” (Sternfeld, 2011, p. 549), by exposing non-Indigenous Australians to information and stories about the land they have grown up and continue to live on. One of the main weaknesses of platform-specific work, which relies on distribution by external parties – in this case Apple – and ubiquitous computing more broadly, is the need for perpetual updating to remain relevant, usable and, in some cases, available at all. For example, an interactive storytelling app developed by the people behind Welcome To Country, Ngurrara: A Ngarluma Story, is now unavailable on the App Store because operating systems at and above iOS 11 no longer support 32-bit apps. Ironically, despite the fact that these developments in digital preservation should be broadening the scope of many of these projects, and expanding the audience for the information they share, the platform specificity and the speed at which these technologies evolve means that such projects, and the stories contained within them, can be forgotten and condemned to an early grave of obsolescence only a few short years after they are released.

Digital historiography’s “potential to generate new, unforeseen historical knowledge” (Sternfeld, 2011, p. 552) is evident in Brett Leavy’s work at Virtual Songlines: an organisation who specialise in Unity-based game design. Similar to Welcome To Country, the archival nature of Virtual Songlines’ work resides in the exploration of pre-colonial space, including site displays and a cultural survival game, both of which make use of geographically accurate pre-invasion settings of Australia’s state capitals. Virtual Songlines’ work strips away the “imperial debris” (Stoler, 2008) of development and allows users to engage with country under the spectre-like gaze of superimposed famous landmarks. Where Stoler discusses the coloniser’s “new zones of uninhabitable space, reassigning [of] inhabitable space, and dictating how people are supposed to live in them” (p. 202), the spaces created by Virtual Songlines were points of first contact for many Indigenous groups as Europeans arrived, and were therefore the first pieces of land to be stolen. This style of representation allows for the simultaneous presentation of what artist Robert Andrew describes as “new and (new) old knowledge” (2018). The work of Ara Irititja, Weerianna Street Media and Virtual Songlines can be thought of as transitional developments in the preservation and dissemination of traditional knowledge in Australia, and indicators that “digital historiography can provide a more seamless transition between analogue and digital work” (Sternfeld, 2011, p. 575) in the archiving of knowledge in various forms.

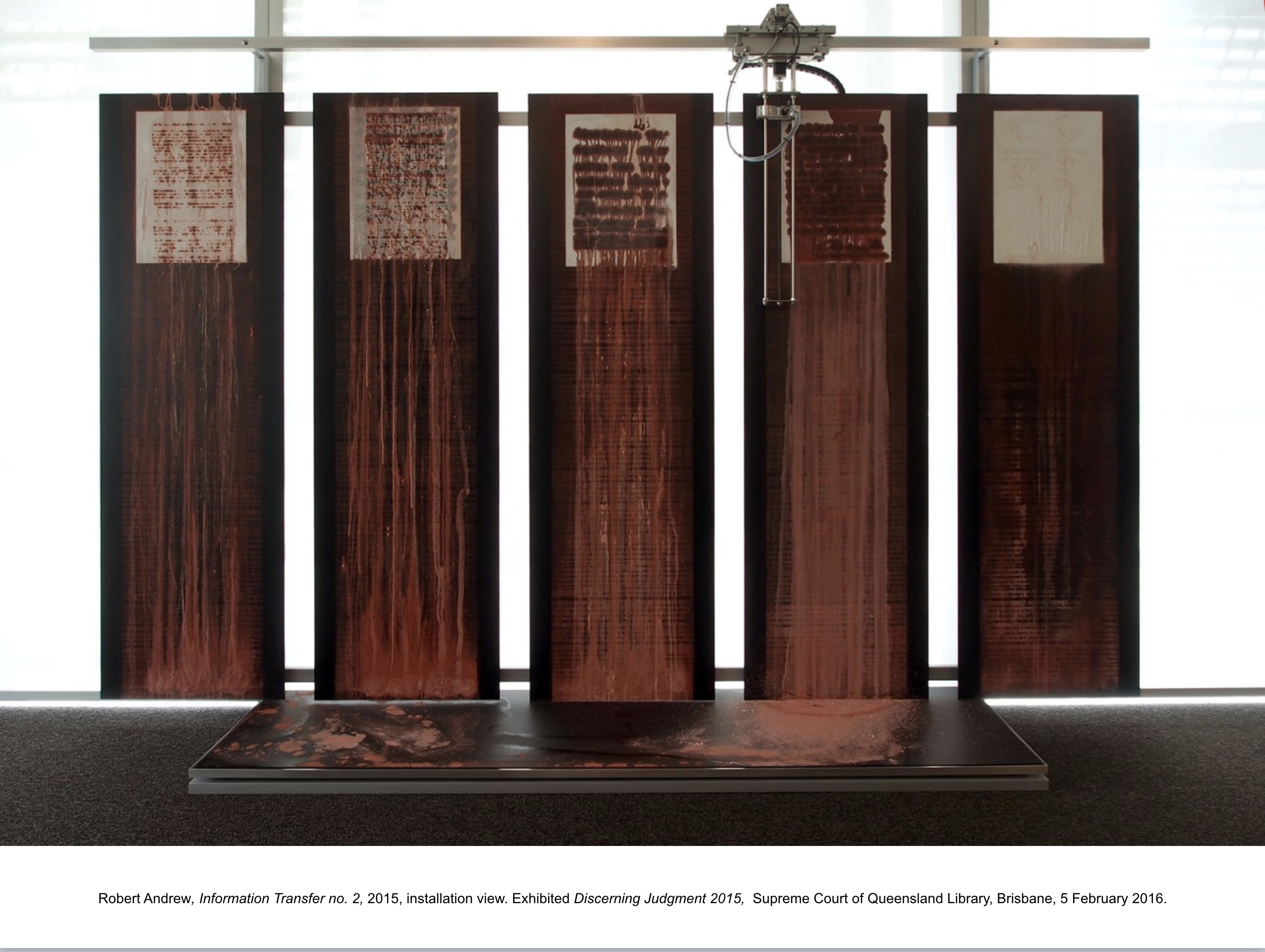

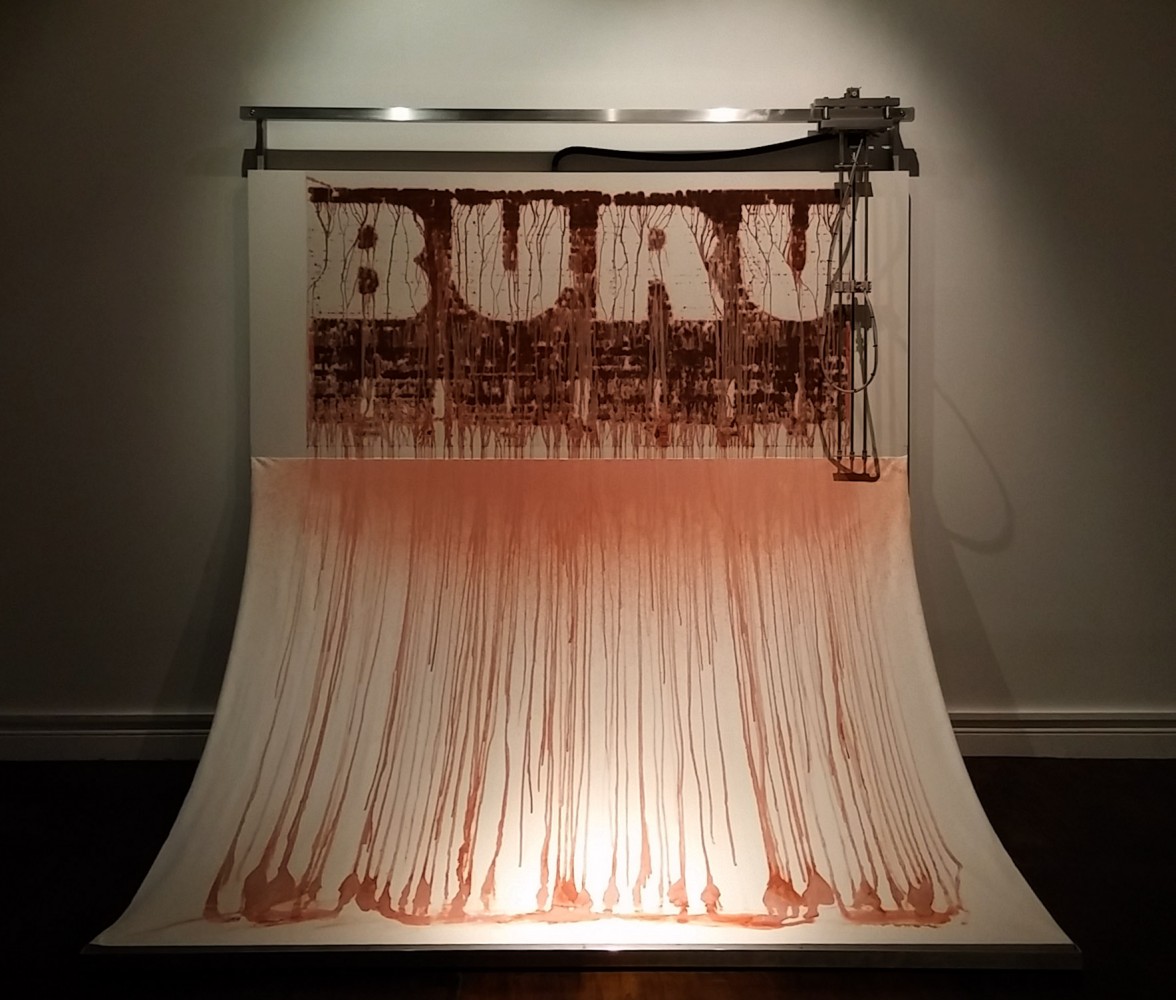

Brisbane-based artist Robert Andrew’s wide-ranging practice involves the use of open source software and hardware in combination with natural processes of weathering to create kinetic works which develop and reveal themselves over days, weeks and, in the case of a new work for Sydney University, even years. Andrew is a descendent of the Yawuru people, whose traditional lands surround and envelop the Western Australian town of Broome, but was unaware of his Indigenous heritage until his early teenage years. Andrew’s work often involves interaction between additive and subtractive methods, which he sees as “fluid resultants of [one another]: a conversation between the covering and the revealing” (2018a). This is an important conceptual area of his work, as it draws attention to his intent to erode Eurocentric narratives and histories, whilst simultaneously revealing Indigenous stories and histories which have been obscured or taken away by colonial, white supremacist systems of governance. Where Sternfeld has stated that new technology can enable a “seamless transition between analogue and digital” (2011, p. 575), Andrew’s work is less about transitioning between the two, and more about “the liminal space created in that conversation [which] is a two-way link between Australian history and Indigenous memory” (2018a). Andrew is particularly engaged with language, which is one of a number of concepts he sees as a “colonising technology… Taking away a culture’s language disconnects strong links to cultural ways of being, seeing and understanding… By redirecting my mechanisms to output non-literal questionings, perspectives and non-prescriptive conversation, I get to work through, and gain insight into, some of my internal conflicts of being Indigenous and non-Indigenous: being the colonised and the coloniser” (2018a). Robert’s pieces Drawn To Experience (2015) and Information Transfer 2 (2015) both make use of electromechanical componentry to erode a “fragile, layered substrate comprising oxides, ochres and chalks” (2018b), with liquids, revealing textures, words and memories over the course of their exhibition. In contrast, Data Stratification (2017), which was shown at Ars Electronica 2017, takes English translations of Yawuru words to be traced by a plotting mechanism. Unlike Drawn To Experience and Information Transfer 2 the plotter does not use any additive or subtractive method to visually represent these words. Instead, it has strings connected to where the printing would take place, which are connected to rows of objects, the movement of which mirrors the shape of the text, drawing attention once again to the logocentric quality of oral history and tradition, and taking away the power of the “colonising technology, [including] all the ways a coloniser’s language is disseminated” (2018a). A forthcoming project of Andrew’s for Sydney University will demand a far longer period of time to develop, relying on and making use of the natural erosion of metals and the trails their disintegration will leave on an external façade of the building into which the work is built. Much of Robert’s work is not necessarily about preserving memory, but searching for memories which were taken before they could be passed down, and attempts to make these processes visual, whether computational or not. In Andrew’s proposal for the work, he states that the word in use “has literal and metaphorical depth and a connected appearance in elements of time and place… all its known and unknown meaning looks at knowledge that is continually accessed, uncovered, placed, displaced, enacted, re-enacted, read, and interpreted: always moving, always growing” (forthcoming, p. 10).

In conclusion, postcolonial usage of a variety of forms of “colonising technology” (Andrew, 2018a) is becoming an increasingly effective way for Indigenous communities to preserve knowledge, memories and stories of people, places, art, and experiences in ways that will continue to develop into the future. Whether through the archiving of materials, stories and artistic output of Ara Irititja, the spatial archiving of Welcome to Country and Virtual Songlines, or the exploration of denied and stolen memory in Robert Andrew’s practice, technological changes and the continuing spread of ubiquitous computing will enable these initiatives and artworks to reach wider audiences and, hopefully, encourage non-Indigenous Australians to consider the history of the land they inhabit: that of world’s oldest continuous cultures, who have resided there since time immemorial. The presentation and medium of the works depends on the audience they are intended for, and the culturally appropriate presentation of knowledge, and information more broadly, is an integral part of their success and continued usage moving forward. Jorgensen, in concluding Indigenous Archives: The Making and Unmaking of Aboriginal Art reiterates Derrida’s assertion that “the impulse to archive, ‘archive fever’, erases the authority of that which is in the archive (p. 424), however, the examples I have provided show that the addition of knowledge to these archives enhances their authority, and the act of archiving in and of itself is in many ways a healing process for the individuals involved in their creation.

References

Andrew, R. (2016) Interviewed by Panoptic Press for Robert Andrew: Recalibrating Country. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EwsGcPadULI

Andrew, R. (2018a) Personal email communication on 20/03/2018.

Andrew, R. (2018b) Drawn To Experience V2 [ONLINE] Available at: http://www.robotandrew.com/portfolio/d2ev2/. [Accessed 21 Mar. 2018].

Andrew, R. (forthcoming) Design Development proposal for Sydney University.

Ara Irititja Project (2011) About Ara Irititja. [ONLINE] Available at: http://www.irititja.com/. [Accessed 18 Mar. 2018].

Christie, M. and Verran, H. (2013) Digital Lives in Postcolonial Aboriginal Australia. Journal of Material Culture, Vol. 18, Issue 3, 299-317.

Commonwealth of Australia (1937) Aboriginal Welfare: Initial Conference of Commonwealth and State Aboriginal Authorities, Canberra, 21-23 April 1937. Available at: https://aiatsis.gov.au/sites/default/files/catalogue_resources/20663.pdf [Accessed 18 Mar. 2018]

Dallwitz, J., Inyika, J., Lowish, S., and Rive, L. (2017) Our Art, Our Way: Towards an Anangu Art History with Art Irititja in: Jorgensen, D. and McLean, I. ed. Indigenous Archives: The Making and Unmaking of Aboriginal Art. Crawley, Western Australia: UWA Publishing. pp. 250-268.

Derrida, J. (1995) Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression. Trans. Eric Prenowitz. Chicago, University of Chicago Press. 1996.

Ekman, U., Bolter, J., Díaz, L., Søndergaard, M. and Engberg, M. (2016) Ubiquitous computing, complexity, and culture. Abingdon: Routledge.

Ekman, U. (2011) Ubicomp Cultures: Hyperbolic Vision, Factual Developments. Fibre Culture Journal, Issue 19, 1-25.

Jorgensen, D. and McLean, I. (2017) Indigenous Archives: The Making and Unmaking of Aboriginal Art. Crawley, Western Australia: UWA Publishing.

Nicholls, C. (2014) ’Dreamtime’ and ‘The Dreaming’ – an introduction. The Conversation. Available at: https://theconversation.com/dreamtime-and-the-dreaming-an-introduction-20833 [Accessed 8 Mar. 2018].

Stanner, W. E. H. (1987) Traditional Aboriginal Society. South Melbourne: McMillan Co. of Australia.

Sternfeld, J. (2011) Archival Theory and Digital Historiography: Selection, Search, and Metadata as Archival Processes for Assessing Historical Contextualization. The American Archivist, Vol. 74, 544-575.

Stoler, A. L. (2008) Imperial Debris: Reflections on Ruins and Ruinations. Cultural Anthropology. Vol. 23, No. 2, 191-219.