Abstract

This practice-based research project is concerned with the practice of self-tracking or biosensing. I will be discussing biosensing specifically in relation to sensing the body in order to understand, protect or promote sexual and or reproductive health[1] using digital applications. These apps, commonly referred to as fertility or menstrual tracking apps, can be installed on mobile devices and allow the user to record variables like the length and quality of menstruation. I will argue that while the practice of biosensing can be an empowering tool for identity construction, the apps themselves figure the menstruating body as straight, female and able-bodied.

Introduction

Biosensing expanded

When referring to biosensing throughout this paper I do so as an expanded practice (Mort and Roberts, 2019). The term biosensor is most commonly used to describe a device for measuring a biological variable using technological methods. Biosensing devices and their sites in the traditional sense are diverse. The term could refer to wearable technologies such as heart rate monitors or implanted blood glucose monitors, or cell-based sensors which can be used to detect pollutants in water or air. Mort and Roberts expand the term biosensing to not only describe these measuring devices but also to refer to a personal practice of observation and manual record keeping. Such practices in relation to personal health and wellness are commonly understood by the term self-tracking. I will be using the terms biosensing and biosensing practitioners as opposed to self-tracking and self-trackers, as I will argue that these practices do not only allow one to keep track, they also form part of how we construct our identities.

Autoethnography

In order to interrogate how biosensing practices construct identity I have used a series of autoethnographic research techniques. I focused specifically on my use of the app Clue, which I have used since 2016. My research included written reflecting of my relationship with Clue via examination of the data collected in the app itself, and comparison with my other biosensing practice of diary keeping. I intensified my use of the app for the duration of one menstrual cycle, using the app daily and keeping reflective notes on my experience. Finally, I began exploring the app as a medium for creative writing, using the apps in built data fields, and my own custom fields. Examples of these writing techniques will punctuate the main body of the text as a series of Drips.

These Drips sit alongside the main body of the text, allowing me to describe my research process in a non-linear fashion. This approach promotes a reflective and playful mediation between the research process and my findings. Moreover, this approach attempts to mirror the fragmentary nature of biosensing as a practice, wherein some senses and contexts are prioritised over others according to the motivations of the practitioner. For example, while I use Clue to track symptoms related to my menstrual cycle, there are other fields I habitually ignore because they don’t suit my particular needs.

Drip – I downloaded my Clue backup. Having set up an account back in 2016 there was a lot of data to look at. Less than you may think given it represents four years of tracking. It appears that I tend to record the first day of my period and then don’t add any further detail until the next first day of my period. Clue therefore thinks I bleed for one day each month. I actually bleed for a lot longer. I couldn’t tell you how long of course, because I don’t write it down.

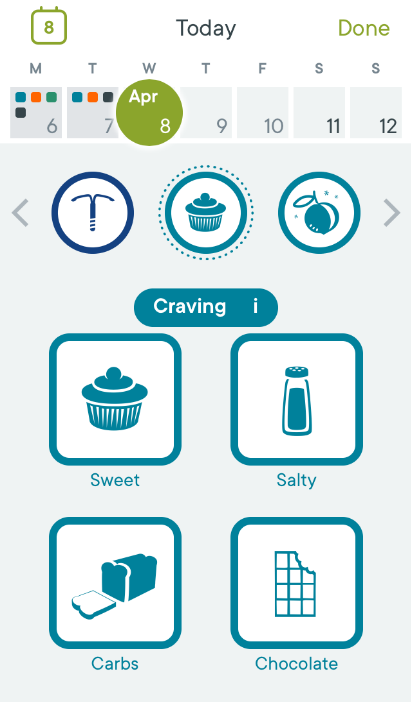

Screen shot of Clue menstrual tracking app. This image shows a view of the app when it is launched on a IOS mobile device. The coloured dots each represent a symptom or variable tracked by the user

Clue

Clue is a widely used menstrual tracking app[2] produced by Biowink GmbH, a company based in Berlin, Germany. It allows users to record their menstrual cycle, alongside other symptoms like headaches or cramping, and custom variables which users define using a free text editor. The app then returns predictions on when the user’s next period may occur, when the user may experience specific symptoms, and provides ‘insights’ into their reproductive health.

The app is free to download and does not require an account to use. It does require an account if the user wants to be able to access their data from another device or recover data if their device is lost or stolen. Clue also claims to be able to make more accurate predictions for those with an account on their website, but they do not go into detail about what this may entail. There is also an option to upgrade to a premium account, which offers ‘a monthly email report of your personal cycle stats. Exclusive content, discounts & giveaways of Clue’s favourite tampons, pads, and period underwear’[3]. A further incentive to subscribe to the premium service includes financially supporting the funding of research into menstrual cycles, which the website presents as under-researched.

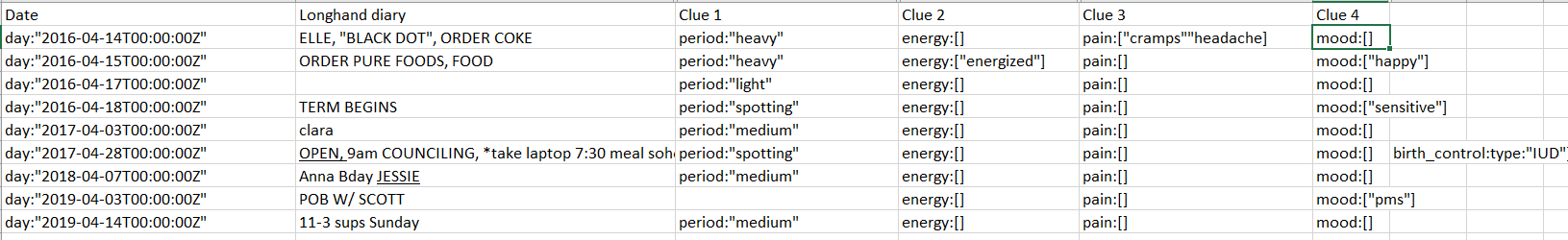

This image shows one of the screens available when logging symptoms via Clue. The user swipes right and left to reveal more options. On this page swiping left takes you to options relating to an IUD, and swiping right toward the peach symbol allows you to record which option best represents your skin on that day; good, oily, dry, acne.

Drip – Your next period will be in 32 days, said clue, and your cycle is on average 35 days long. I added up the length of my recorded cycles, divided them by the number of months to get an average. The average was 34 days. It would appear that’s how that is done, which makes sense.

Why Biosense?

Biosensing as a practice is not passive but involves the observation of embodied experience, and development of a language with which to record these observations. It also requires the practitioner to devise a system of judgements to identify what is useful to record in their particular circumstances and what is not. Users of menstrual tracking apps use them for a variety of reasons. These can include managing fertility tracking the effects of hormonal supplements and medications, tracking symptoms of the menstrual cycle or as a convenient way of estimating when you might next menstruate (Lupton, 2015; Karlsson, 2019; Mort and Roberts, 2019). Apps are also used in order to veil menstrual tracking when other forms of record keeping, like marking the start of your period on a calendar which can be more visible to others, for example in the work place (Karlsson, 2019).

The motivations for using menstrual tracking apps, as well as the data recorded, are often nuanced and intensely personal. Biosensing is therefore not only a (somewhat) objective record of a particular set of variables related to a body, it is also a practice which reflects the specific situation, motivation and relationships of the biosensing practitioner. Practitioners have described ignoring app features which they don’t find useful, contesting the insight the apps provide if they are not appropriate, while still finding the process in some way empowering (Sharon and Zandbergen, 2017; Thomas, Nafus and Sherman, 2018). It is in this way that biosensing practices are entangled in our understanding of self.

Data in these types of self-tracking practices are a new element in an aesthetic and continuous process of identity construction. It is not just used to learn about oneself but also to construct stories about oneself. (Sharon and Zandbergen, 2017)

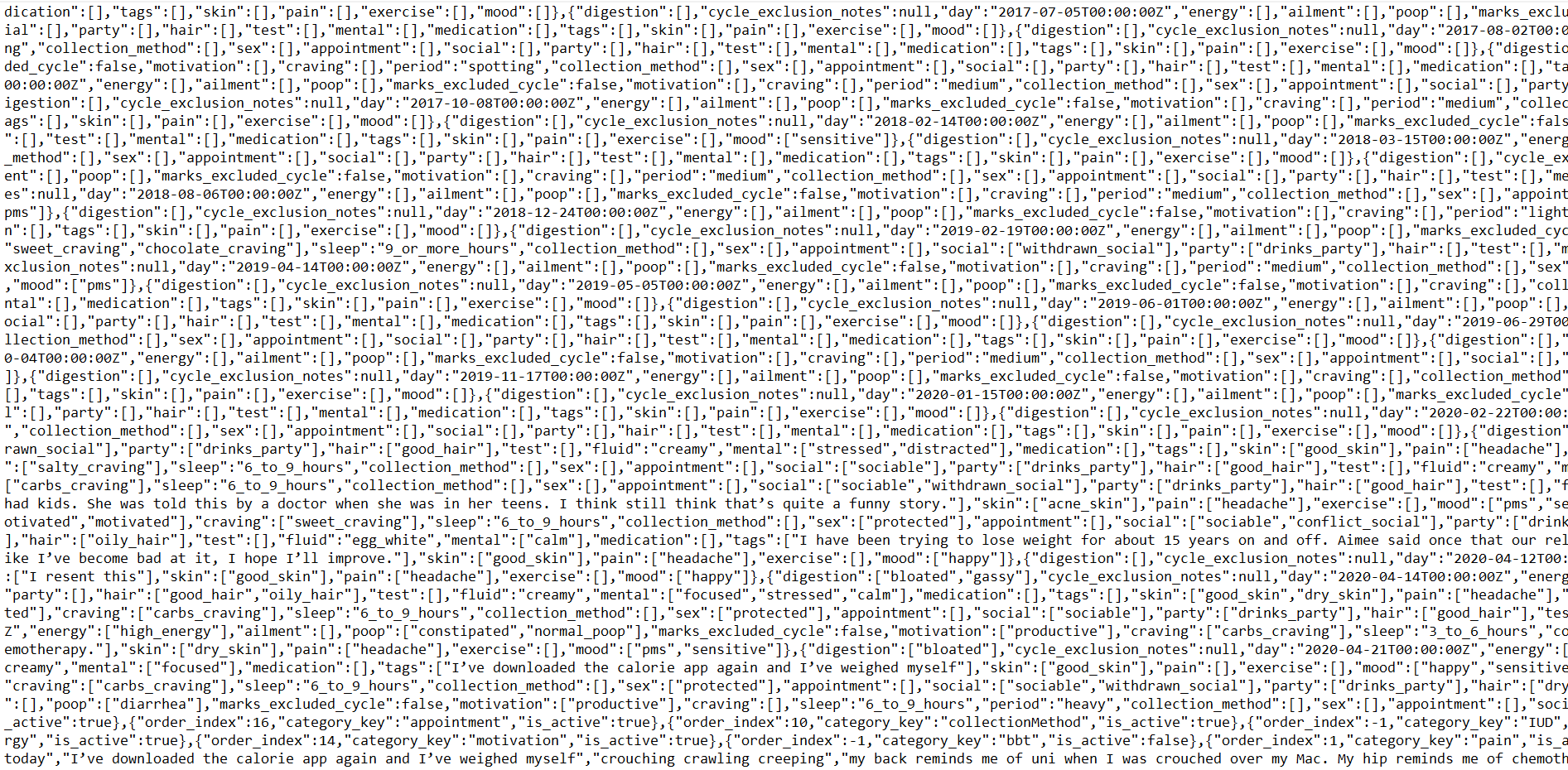

This image shows records of records from Clue and records from my long hand diary, made on the same day.

Drip - I bled through my clothes twice today and I have a headache. I am the author of this essay, the researcher of these topics, the biosensing practitioner, artist and period haver. I am a person who currently menstruates, is currently menstruating, who is sexually active. I am cis-gendered. As far as I’m aware, I have the ability to become pregnant, but at this moment do not want to be pregnant. I have managed reproductive health issues, and other health issues which have impacted my menstrual cycle. I am lucky enough to feel able to discuss menstruation in a public forum although a stigma around periods exists, in my experience. I’m white, I’m housed and in post graduate education.

I’ve missed periods due to stress or simply due to that being how my body works. I’ve missed them on purpose with the use contraceptions or have chosen exactly when to have them using other types of contraceptions and stopped them semi-on-purpose as a side effect of chemotherapy. I have suffered intense changes in mood as a direct result of the contraceptive pill and now use a copper coil specifically because it doesn’t use hormones to control fertility. I continue to experience changes in mood around my period and use self-tracking so I am able to validate my feelings of low mood. It allows me to understand my emotional state better… or dismiss behaviour as a result of PMS – am I going mad, or am I ‘legitimately’ upset? I’ve yet to decide whether it matters. Sometimes it does, sometimes it doesn’t.

I have used Clue to track my period since at least February 2016. I’ve also used red dots in diaries. I’ve forgotten about it completely only for it to turn up at inopportune moments. One day I might use the moon or the tides, one day I might just know when it comes. One day I may not care to know and certainly one day I won’t have a period to worry about anyway.

Insights

In the case of fertility biosensing apps, not only do the apps become a meaningful feature of the body’s present through repeated use, they can also work to configure a potential future for the user through predictions and advice based on the data they record. Clue specifically put the apps ability to predict the timing and quality of your menstrual cycle at forefront of its literature, to the extent the app itself allows you to set reminders for the onset of certain symptoms. In addition to being a convenient or discrete way of recording menstruation, menstrual tracking apps are marketed as empowering technologies which help menstruators understand their bodies more fully through self-reflection and information provided by the app.

While I would agree that the practice of biosensing can be of benefit to the user, I believe the predictive and advice-giving capacities of these apps deserve further scrutiny. Opinions on the efficacy of the predictive algorithms of menstrual apps has been mixed (Berglund Scherwitzl et al., 2016; Freis et al., 2018), in part because it relies on the accuracy of the user data, and because the often proprietary algorithms are hard to access and assess. The apps themselves have also come under criticism for assuming that users are straight, cis gendered and able bodied (Lupton, 2015; Søndergaard, 2017; Kressbach, 2019; Mort and Roberts, 2019), both undermining their own rhetoric of empowerment and the accuracy of their algorithms by not taking into account the experiences of some menstruators.

Finally, some researchers have identified that, more so than the app itself, biosensing practitioners find that real insights and useful advice come from the community of users (Sharon and Zandbergen, 2017; Thomas, Nafus and Sherman, 2018; Mort and Roberts, 2019). When using menstrual apps our own data is often little more than ‘a speck in the larger sea of data’ (Mort and Roberts, 2019) and therefore an individual user is largely disconnected from the rest of the user base. In the case of Clue, very little recourse is available in order to contest or query any of the advice the app gives – or evaluate your data in comparison with that of fellow practitioners.

Drip – I started recording how I feel in Clue at roughly the same time every day. Clue presents you with a sequence of options to choose from, encouraging you to log more symptoms in order to gain better understanding of your cycle. This better understanding is delivered to you through short text which appear as banners. I’ve turned them all on, apart from BSTemp which I had to look up and seems like a faff. I find it curious that although it has a number of sections to record sex and contraception, this doesn’t include a way of recording the morning after pill, pregnancy or abortion. Also, apparently my period is outside of the normal range of deviation and I should consult a GP.

Screen shot of ClueDataExport.cluedata file showing my Clue entries, including custom data fields used as space for creative writing.

Reflections

As I explained earlier, my autoethnographic research practice by was by nature, very specifically bound to my experience of using Clue. I chose this approach for a number of reasons. As we have discussed, use of menstrual tracking apps can reflect the very personal motivations of the user, aside from the fact that data itself may contain accounts of bodily functions some are not comfortable sharing publicly. Ethically, using my own personal data meant I could be sure I would not undermine the privacy of another users personal data, and practically (and in some ways reassuringly) Clue do not publicly release user data to developers, meaning large sets of user data is difficult to come by in this instance. While some very kind colleagues did provide me with their menstrual tracking app data, I was not in the position to interview them in person for this study, which would be my preference given the sensitivity of the subject. Given that many people note sexual encounters in menstrual apps, I have not only the users privacy to consider but also that of their sexual partners.

What autoethnography did afford me was the opportunity to tell a personal account. By reflecting on my own app data and comparing it to long hand diary entries, I was able to better understand how these forms of biosensing worked to construct different versions of my past. Daily interactions with the app became both a point to mindfully reflect on my embodied experience, and this project itself; my motivations, preconceptions and biases. When I began to use the app to record snippets of narratives or poetry, I became more explicitly aware of how my use of Clue had always been a part of my construction of identity. For example, it became clear that my use of Clue peaked in frequency in the days leading up to my period when I would start tracking my mood. I have been using the app as a tool contextualise and rationalise instances of low mood. Although I had not understood it as such, I have come to understand my practice of biosensing through menstrual apps as a tool to qualify my experiences.

This approach is of course very limiting in terms of my authority to comment on menstrual tracking technology in relation to wider discourses. This project touches briefly on menstrual stigma and systemic gender inequality within healthcare systems, but to make more robust assertions would require perhaps a phenomenographic approach to identify variances in experience. There is also much to be discussed in terms of how menstrual tracking technologies are could be as tools of menstrual activism through design fictions, building on the existing work of practice based researchers (see Almeida et al., 2016; Søndergaard and Hansen, 2016). I believe that menstrual tracking apps’ use of proprietary file types and algorithms also warrants further study, as do the labour practices and ethics of ‘big data’ in relation to healthcare.

Drip – There are custom data fields you can use, apart from the built in options. These are free text. Users are given two examples – Cervix high and hard, Cervix low and soft. The app lets you know that the more information you give them, the better it can get at predicting how you might feel. I’ve started to use this section to make notes about my day and reflections on this project or just words which seem appropriate. One day I wondered how these custom data fields could be used to make meaningful predictions about the user, or whether they are orphaned records which are not used as part of Clue’s system of ‘Insights’. I suppose that these fields are manually cleaned and coded. I wrote a note in the custom field to ask whoever was doing the cleaning whether my supposition was correct, and to apologise for giving them more work. The next day I told them a joke by way of apology.

[1]Although I refer to sexual and reproductive health throughout this essay, it is with the full understanding that menstruation does not equal the ability or desire to reproduce, nor are conversations around menstruation predicated on heteronormative notions of sexuality and sexual activity.

[2] 913,339 downloads on the Google play store, and over 66,400 reviews on the IOS App Store (IOS App Store do not publish number of downloads, but is safe to assume the number of users exceeds the amount of people who rate it).

[3] For more information about Clue’s premium service visit https://helloclue.com/articles/about-clue/introducing-clue-plus

Annotated bibliography

Mort, M. and Roberts, C. (2019) Living Data: Making Sense of Health Biosensing. Policy Press.

This text interrogates how individuals use data collected about their health, and how that data is then used to inform their identity, relationship with their bodies and traditional health care systems. My research here was particularly influenced by the framing of self-tracking as biosensing, a term which acknowledges self-tracking as a form of biographical narration.

Sharon, T. and Zandbergen, D. (2017) ‘From data fetishism to quantifying selves: Self-tracking practices and the other values of data’, New Media & Society. SAGE Publications, 19(11), pp. 1695–1709. doi: 10.1177/1461444816636090.

This paper discussed how member of the Quantified Self community ascribe value and meaning to the data they collect through self tracking practices. The authors argue than rather than fetishize data and ascribe it authority over lived experience, self trackers use tracking as a practice of mindfulness.

Thomas, S. L., Nafus, D. and Sherman, J. (2018) ‘Algorithms as fetish: Faith and possibility in algorithmic work’, Big Data & Society. SAGE Publications Ltd, 5(1), p. 2053951717751552. doi: 10.1177/2053951717751552.

This paper discusses how power is assigned to algorithms, and how the capabilities of algorithms are understood as ‘magical’ and objective. It also uses the lens of fetishism to understand the social and economic value assigned to types of data labour. The paper influenced how I came to think consider the authority of menstrual app predictions.

Full bibliography

Almeida, T. et al. (2016) ‘On Looking at the Vagina through Labella’, in Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. San Jose, California, USA: Association for Computing Machinery (CHI ’16), pp. 1810–1821. doi: 10.1145/2858036.2858119.

Berglund Scherwitzl, E. et al. (2016) ‘Fertility awareness-based mobile application for contraception’, The European Journal of Contraception & Reproductive Health Care, 21(3), pp. 234–241. doi: 10.3109/13625187.2016.1154143.

Freis, A. et al. (2018) ‘Plausibility of Menstrual Cycle Apps Claiming to Support Conception’, Frontiers in Public Health, 6. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00098.

Garrett, M. (2018) ‘Unlocking Proprietoral Systems for Artistic Practice’, A Peer-Reviewed Journal About, 7(1), pp. 100–112. doi: 10.7146/aprja.v7i1.115068.

Hester, H. (2018) Xenofeminism. Cambridge, UK ; Medford, MA: Polity Press (Theory redux).

Hughes, B. (2018) ‘Challenging Menstrual Norms in Online Medical Advice: Deconstructing Stigma through Entangled Art Practice’, Feminist Encounters: A Journal of Critical Studies in Culture and Politics. Lectito Journals, 2(2). doi: 10.20897/femenc/3883.

Karlsson, A. (2019) ‘A Room of One’s Own?’, Nordicom Review; Gothenburg, 40(s1), pp. 111–123. doi: http://dx.doi.org.gold.idm.oclc.org/10.2478/nor-2019-0017.

Kressbach, M. (2019) ‘Period Hacks: Menstruating in the Big Data Paradigm’, Television & New Media. SAGE Publications, p. 1527476419886389. doi: 10.1177/1527476419886389.

Law, J. (2019)'Material Semiotics' ‘Law2019MaterialSemiotics.pdf’ (2019). Available at: http://www.heterogeneities.net/publications/Law2019MaterialSemiotics.pdf (Accessed: 1 May 2020).

Lupton, D. (2015) ‘Quantified sex: a critical analysis of sexual and reproductive self-tracking using apps’, Culture, Health & Sexuality, 17(4), pp. 440–453. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2014.920528.

Manica, D. T. et al. (2017) ‘(In)visible Blood: menstrual performances and body art’, Vibrant: Virtual Brazilian Anthropology. Associação Brasileira de Antropologia (ABA), 14(1). doi: 10.1590/1809-43412017v14n1p124.

Mort, M. and Roberts, C. (2019) Living Data: Making Sense of Health Biosensing. Policy Press.

Pink, S. et al. (eds) (2016) Digital ethnography: principles and practice. Los Angeles: SAGE.

Plows, A. and Boddington, P. (2006) ‘Troubles with biocitizenship?’, Genomics, Society and Policy, 2(3), p. 115. doi: 10.1186/1746-5354-2-3-115.

Sharon, T. and Zandbergen, D. (2017) ‘From data fetishism to quantifying selves: Self-tracking practices and the other values of data’, New Media & Society. SAGE Publications, 19(11), pp. 1695–1709. doi: 10.1177/1461444816636090.

Søndergaard, M. L. J. (2017) ‘Intimate Design: Designing Intimacy As a Critical-Feminist Practice’, in Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems - CHI EA ’17. the 2017 CHI Conference Extended Abstracts, Denver, Colorado, USA: ACM Press, pp. 320–325. doi: 10.1145/3027063.3027138.

Søndergaard, M. L. J. and Hansen, L. K. (2016) ‘PeriodShare: A Bloody Design Fiction’, in Proceedings of the 9th Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction. Gothenburg, Sweden: Association for Computing Machinery (NordiCHI ’16), pp. 1–6. doi: 10.1145/2971485.2996748.

Thomas, S. L., Nafus, D. and Sherman, J. (2018) ‘Algorithms as fetish: Faith and possibility in algorithmic work’, Big Data & Society. SAGE Publications Ltd, 5(1), p. 2053951717751552. doi: 10.1177/2053951717751552.

Thornton, P. (2018) ‘Language Redux’, A Peer-Reviewed Journal About, 7(1), pp. 8–11. doi: 10.7146/aprja.v7i1.115056.

Wong, A. L. (2018) ‘Artists in The Creative Economy’, A Peer-Reviewed Journal About, 7(1), pp. 114–126. doi: 10.7146/aprja.v7i1.116059.