Individuated actualizations amidst ubiquity effects

Aaron Dore & David Williams

Background

For our research project and resulting artefact, we decided to focus on the notion of ubiquitous computing. Ubiquitous computing as a term was first coined by computer scientist Mark Weiser in the late 1980’s, who envisaged a ‘third wave’ of computing which moved away from personal computers and towards computational devices which are ‘embedded’ into our everyday lives. “The most profound technologies are those that disappear. They weave themselves into the fabric of our everyday lives until they are indistinguishable from it.”

Several years on, ubiquitous computing is still a term which is used by theorists in several fields, and although we can see that the ‘personal computer’ paradigm has not been superseded, nonetheless we can now find computational devices pervading many parts of our lives, from our mobile ‘smart’ phones, environmental monitoring devices, contactless travel payments and surveillance technologies, to name but a few. As technology in the context of embedded ‘smart’ devices makes a continuous move towards becoming more efficiently networked, we are challenged to re-think our relationship to computers – it is no longer a case of interacting with an inert device via a screen with a keyboard and mouse, instead, as Alois Ferscha puts it, “the environment is the interface”. The implications of these new technologies are indeed profound and as such, the study of ubiquitous computing has become a vast field of research in its own right and one that demands an awareness of interdisciplinary research approaches.

When deciding on a research object, the first challenge was how to decide which aspect of ubiquitous computing to focus on. Our first idea was to look at ubiquitous surveillance through accessing unsecured IP-cameras. There are a number of websites which offer access to an archive of unsecured networked camera devices all around the world. We envisaged an idea of an ‘aesthetics of excess’ in relation to surveillance technology, where statistical analysis of live streamed data co-operated with computer vision in order to record and catalogue ‘meaningful’ visual data so a representation of ‘waste’ data could be presented in a visual manner, within a computational artwork. However, we found that this area contained some problematic ethical issues in context to the webcam content and so we turned instead to devices that we ourselves use on an everyday basis.

Many ubiquitous technologies, being so well embedded, are really at the periphery of our normal attention. An example of this is contactless travel payment. We ‘tap in’ and ‘tap out’ more or less automatically, without giving much though as to journey we are taking. The payment will show up on bank statements but with no indication of where or even how we used a particular travel service. As a way of highlighting this, we wanted to try and reverse this automatic process back to the centre of attention. As such, whenever we used a contactless payment service, we would send each other a locational ‘pin’ via the WhatsApp messenger app. We would then build up something of a locational map of where we had travelled, with some added context such as the date and time of our travels. This was interesting to a point, but we realised from gathering this information that by using GPS location apps, we could retrieve the data in the form of a .GPX file which could be read by a computer, so theoretically, we could create us of ‘map’ visualisation based on this data. From a theoretical perspective this was also interesting, in the sense of how we ‘individuate’ based on where and how we travel. Put very simply, individuation is way in which one thing is made distinct from another. This idea has its roots in a wide array of philosophical thought, but it is also something which is exploited by the technological media – as relevant to our studies this is evident in Google’s ‘location services’, which via tracking a device’s location can tell where you live, where you work, what shops you visit and where you go in your free time. All of this data, when processed through computational algorithms, builds up a unique portrait of any given individual using their services.

We wanted to create something like this for our artefact (without of course the ulterior motives of a corporate location service such as Google’s), using the .GPX data gathered from a basic GPS recording app installed on our mobile phones.

The Artefact

With the rise of mobile computing in the form of ‘smart’ phones, the vast majority of people living in the UK, (in the global north in-fact), carry with them on a day-to-day basis such a device. Such devices can be said to have become ‘ubiquitous’ with modern living. These devices are considered ‘smart’ because that they carry within them a variety of sensors - they have moved beyond the ability to make phone calls, but also now allow users to browse the internet, take photographs, read documents on the fly, as well as tell us where we are in the world using an integrated Global Positioning System, or GPS.

This GPS can be made available to the user via a GPS tracking application – many basic independent versions are available at no cost on several mobile platforms. These types of tracking apps records GPS data and stores it as a .GPX file (amongst other formats), which can be ‘read’ by other GPS apps, or to put it more simply, can be used as data input for a computer program. This is where we got the inspiration for producing a research ‘artefact’. We could write a basic computer program which utilised this GPS data and create our own personalised ‘maps’.

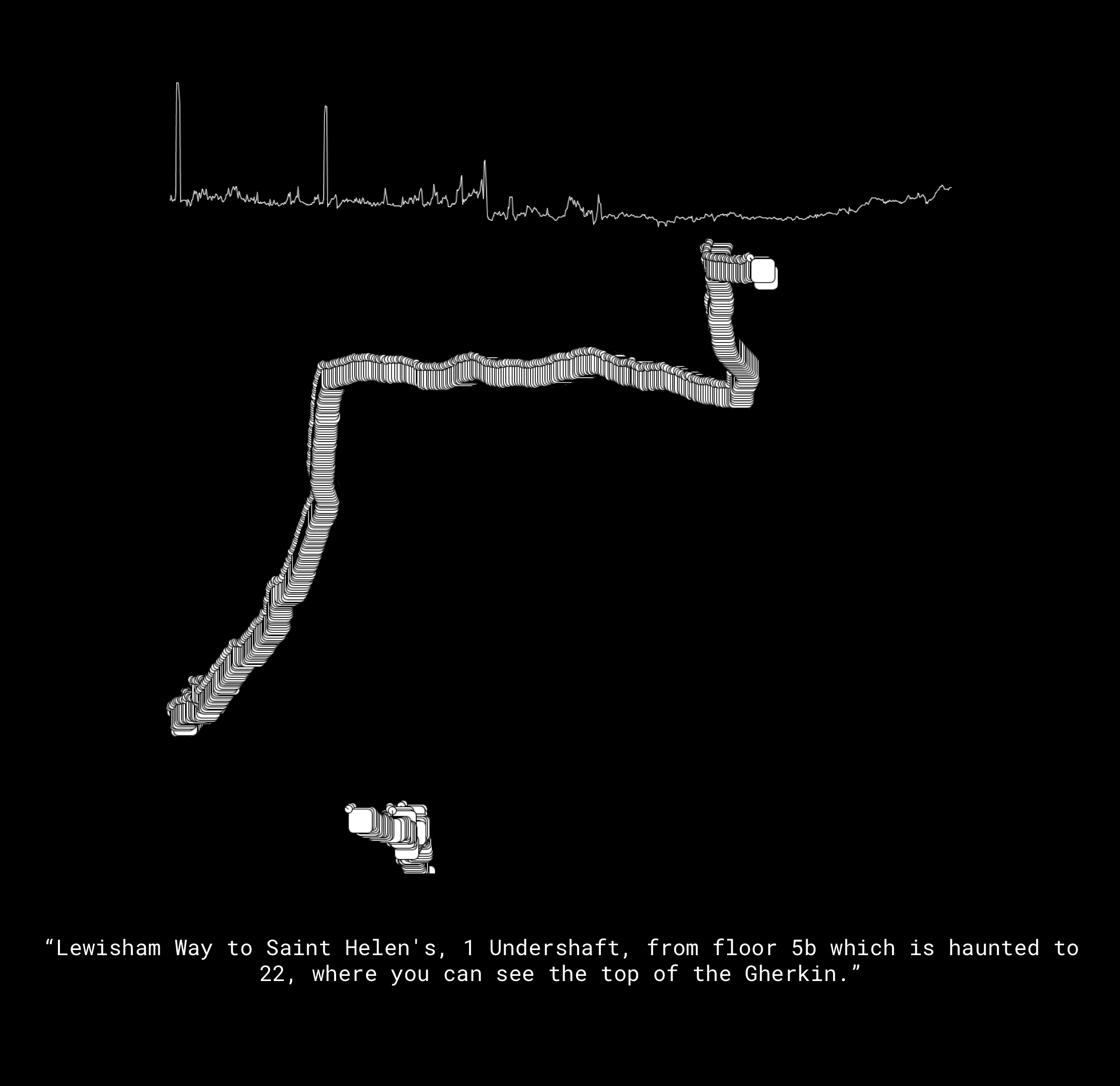

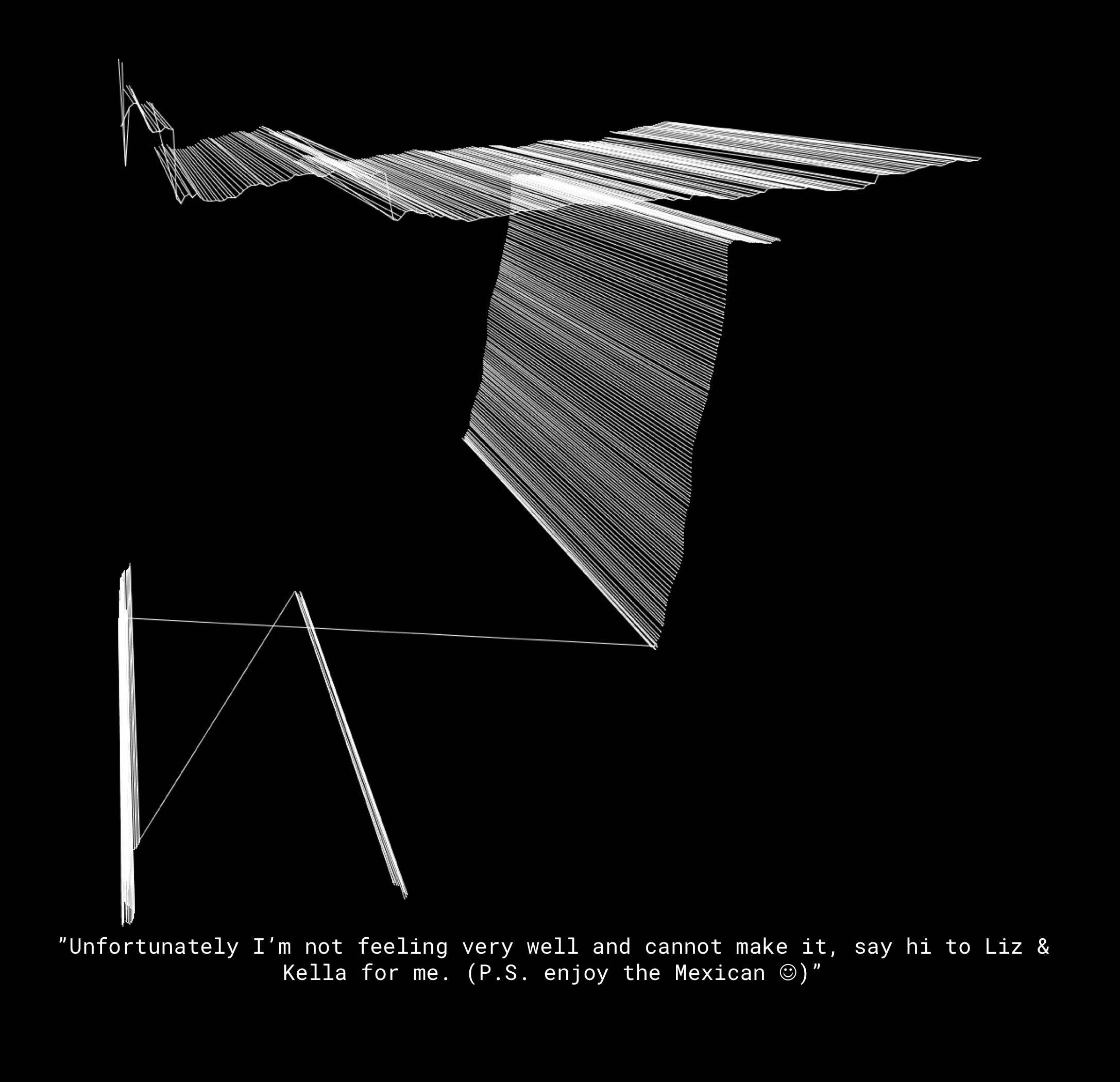

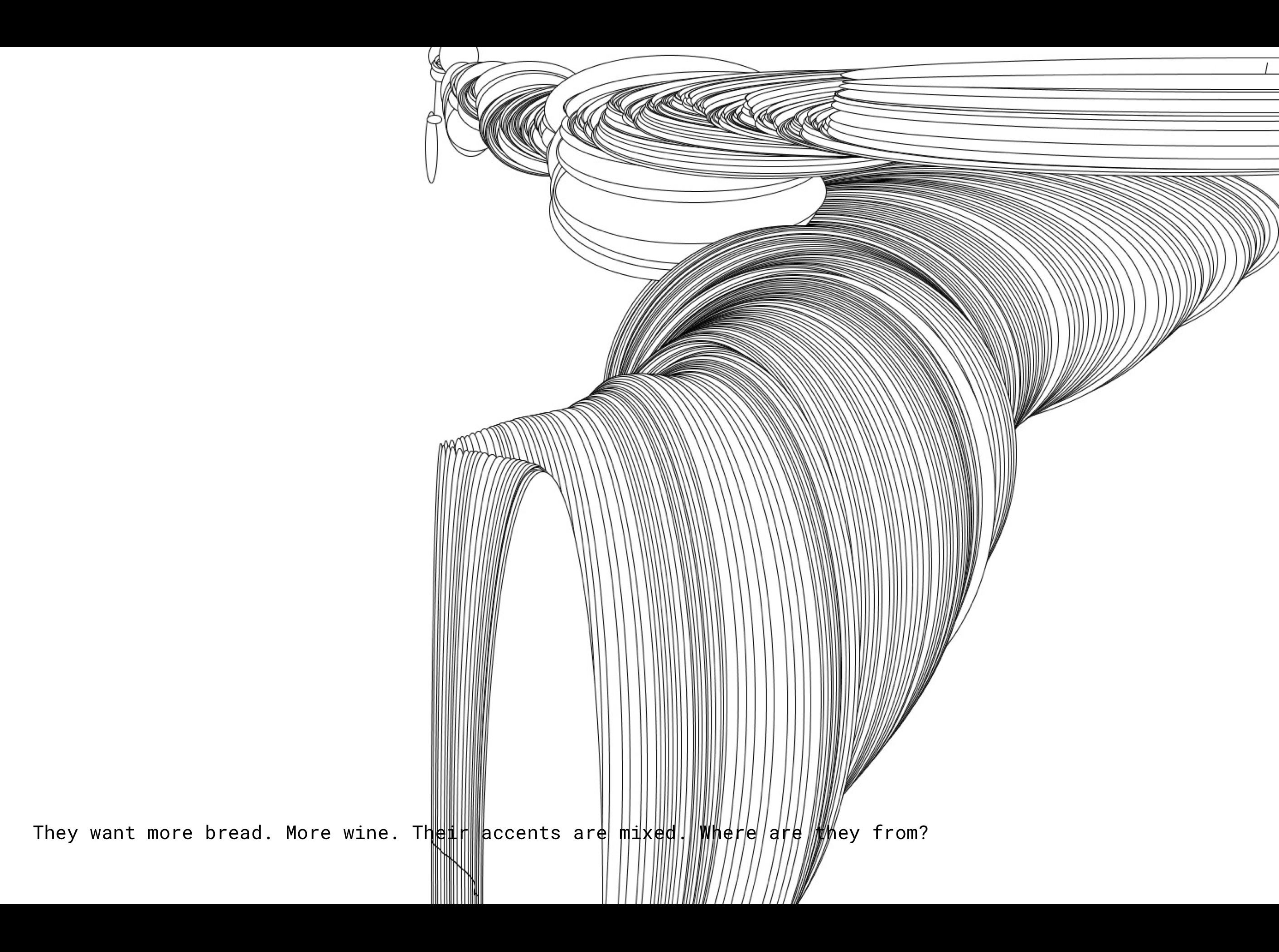

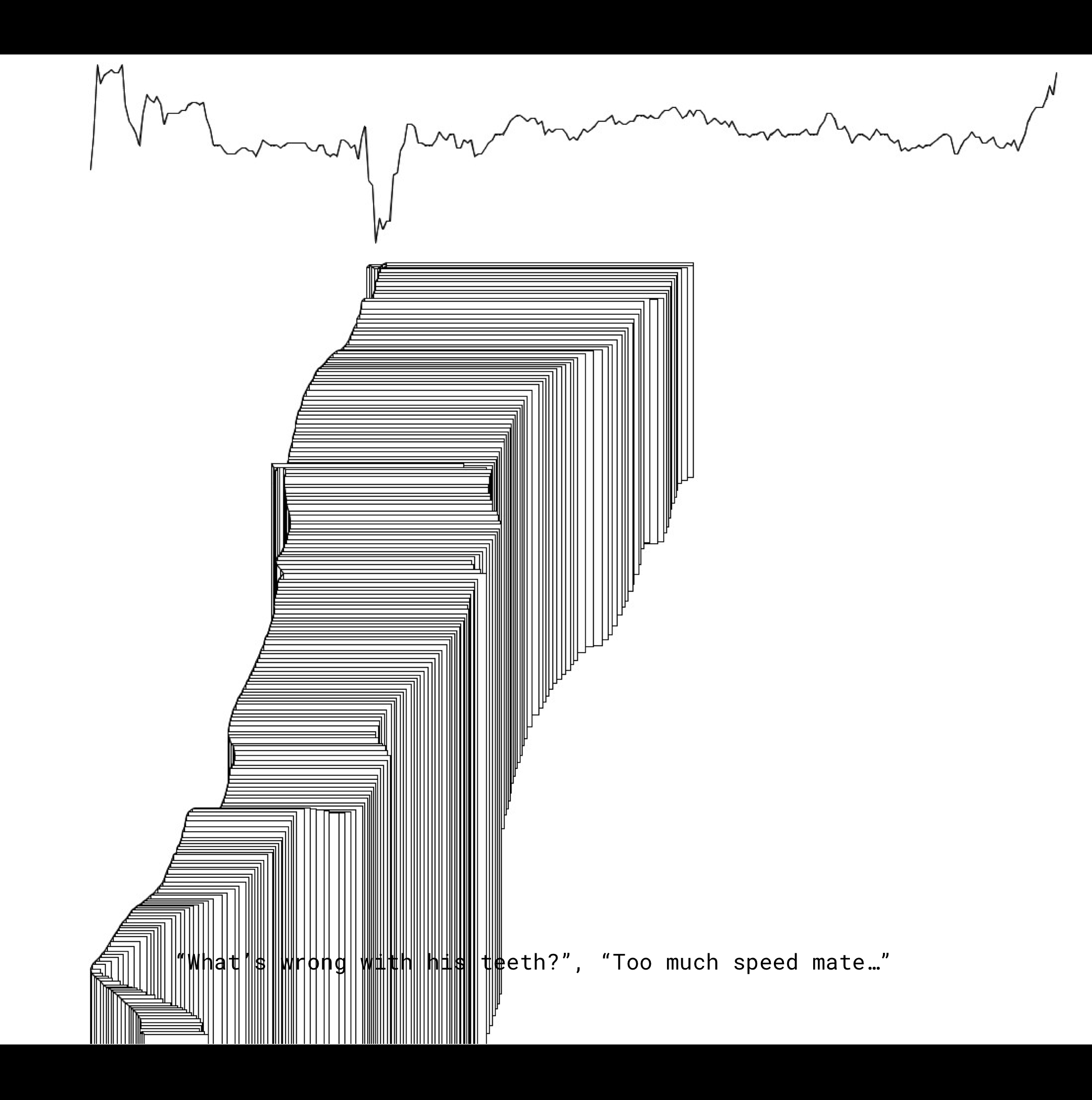

Our final creation was a program created using the Processing Language. We utilised the ‘processing-gpx’ library which is available on GitHub, and borrowed some pieces of code that assist in translating GPS coordinates to pixel space. The code can then be adapted so that we could in a sense ‘draw’ our own maps in whatever way necessary, based on GPS data which we had gathered from travelling around London.

By giving each map a written title, the work explores the individuated relationships we attain via our distinct negotiations with the manifestations of ubiquity artefacts. It is the works intention to function as a reminder that Individuals should find comfort in the agency of complex emergent systems, over the alternative scenarios in which the dissolution of self and refusal of individuated actualisation unfolds as a social, political and technic dependency.

References

Ubiquitous Computing, Complexity and Culture 1 by Ulrik Ekman, Jay David Bolter, Lily Díaz, Morten Søndergaard, Maria Engberg (ISBN: 9780415743822) 2017

This Pervasive Day: The Potential and Perils of Pervasive Computing by Jeremy Pitt (ISBN: 9781848167483) 2012

Walking and Mapping: Artists as Cartographers Leonardo Book Series Author Karen O'RourkeEdition MIT Press, 2016 ISBN 0262528959, 9780262528955