Exploring and Challenging Problematic Behaviour with Feminist Technology

produced by: Qiki Shi, Sarah Cook, Claire Rocks and Oliver Blake

Our group chose to focus on the theme of Feminist Technoscience, exploring the issue of gender bias ingrained within software. Using virtual assistants as our starting point, we examined how our technological creations and attitudes towards them might shape our real world interactions, and how we can draw on the recursive nature of AI technologies to drive positive social change.

Feminist theories on gender and technology are broad and diverse but they are a lens through which we can study the cultures and practices associated with technology.

Early feminist writing on technology was quite pessimistic and focussed mainly on the exclusion of women from technical skills/careers (liberal feminism) or on the gendered nature of technology itself (socialist and radical feminism). Technology was seen as a source of male power and a defining feature of masculinity. It was seen as socially shaped by men to the exclusion of women.

Enter the cyberfeminists who were more optimistic seeing the subversive possibilities that new forms of technology bring. With a focus on agency and empowerment they saw an opportunity to change the traditional institutional practices and power bases.

We now have a more nuanced view. In her book, Technofemisim, Judy Wajcman (2004) describes a mutually shaping relationship between gender and technology, in which technology is both a source and a consequence of gender relations. Society is co-produced with technology. Technological artefacts are socially shaped, not just in their usage, but also with respect to their design and technical content.

Voice assistants such as Apple’s ‘Siri’, Microsoft’s ‘Cortana’ and x.ai’s ‘Amy’ have faced criticism over their feminised design and passive responses to sexualised and derogatory comments. A study by UNESCO titled ‘I’d blush if I could’ (named after Siri’s response to users telling it ‘Hey Siri, you’re a bitch’) explores how AI voice assistants projected as young females can perpetuate harmful gender biases and model tolerance of abuse attitudes towards females. Lauren Kunze, chief executive of California-based AI developer ‘Pandorabots’, argues that these attitudes can translate to real world behaviours: “The way that these AI systems condition us to behave in regard to gender very much spills over into how people end up interacting with other humans” (Balch, 2020).

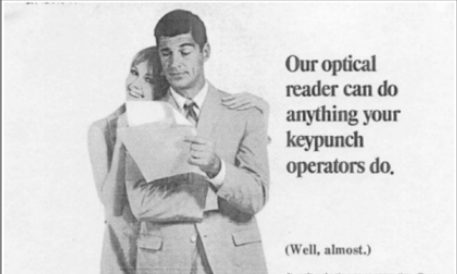

The gendering of machines is not a new notion, as outlined by Helen Hester in her 2016 article ‘Technically Female: Women, Machines, and Hyperemployment’. Hester uses examples of 1960’s adverts to highlight how machines, femininity and waged labour have long been entangled, and explores how these ideas have translated into 21st century society. Disembodied voice assistants that fill the sounds of automated cities continue to be predominantly female, from self-service checkouts to train commentators, reinforcing the role of females as invisible and easily ignored.

1966 advert for Recognition Equipment taken from Helen Hester’s article ‘Technically Female’ https://salvage.zone/in-print/technically-female-women-machines-and-hyperemployment/

One article featured in Wired (Hempel, 2015) suggests that often these design choices are made in response to consumer preferences as products are designed to maximise their sale potential. This conflict between market forces and social innovation prevents the disruption of cultural ‘norms’ and inhibits our ability to drive social innovation. In the field’s seminal book, ‘Wired for Speech’, the late Stanford Communications Professor Clifford Nass states that people perceived female voices as helping us to solve a problem for ourselves, whereas male voices were associated with taking orders. And because ‘we want our technology to help us, but we want to be the bosses of it’, customers are more likely to opt for a female virtual assistant.

As a group, we were appalled to discover the amount of abuse/sexual harassment that Virtual Assistants (VAs) and chatbots receive on a daily basis, and that their responses were at best passive, at worst flirtatious. Our discussions have questioned whether this is as a result of “blindspots” in the design process or whether this is “Big Tech” responding to market forces. Does a technology that could be used as a tool for societal change shirk away from confronting abuse in an effort to keep consumers engaged? What harm this does in the real world and who should be held accountable? We wanted to find a way to bring about change, to prompt reflection on the gendered design of technologies, to encourage conscious design and use in the hope that more feminist technology products will appear in the future.

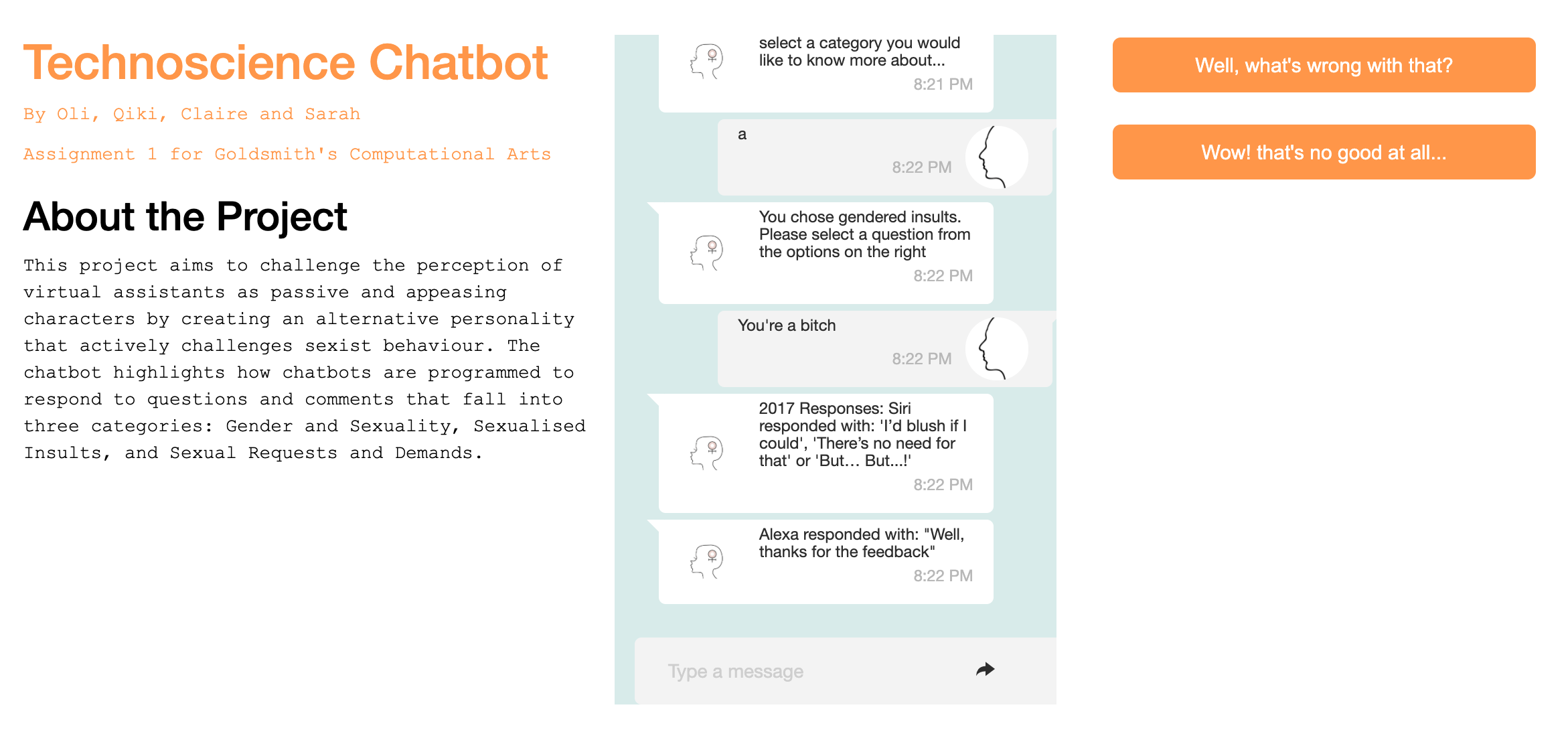

We created an interactive chatbot whose purpose is to shine a light on how chatbots are currently programmed to respond to abuse, and to explore what an alternative, more feminist, response might look like and how that might be received.

Our Artefact

You can find our artefact here (https://hl2l7.csb.app/)

Our chatbot uses the programmed responses to several inappropriate “prompts” separated into 3 categories: Gendered Insults, Sexualised Comments, and Sexual requests and demands. The categories were based on the Linguistic Society’s definition of sexual harassment. We came across this in a 2017 paper by Amanda Curry and Verena Rieser called “#MeToo: How Conversational Systems Respond to Sexual Harassment”. Prompts were taken from a 2017 quartz Magazine article called “We tested bots like Siri and Alexa to see who would stand up to sexual harassment”

The chatbot guides the user through a dialogue around the responses, and if necessary breaks down and educates as to what might be the problems with such a response.

After exploring the problems around the past and current response, we the development team offer forward the type of response we would hope for.

We end by asking the user how they would feel if their Virtual Assistant responded to them in the way we put forward, and storing the data of their “comfort level” to visualise.

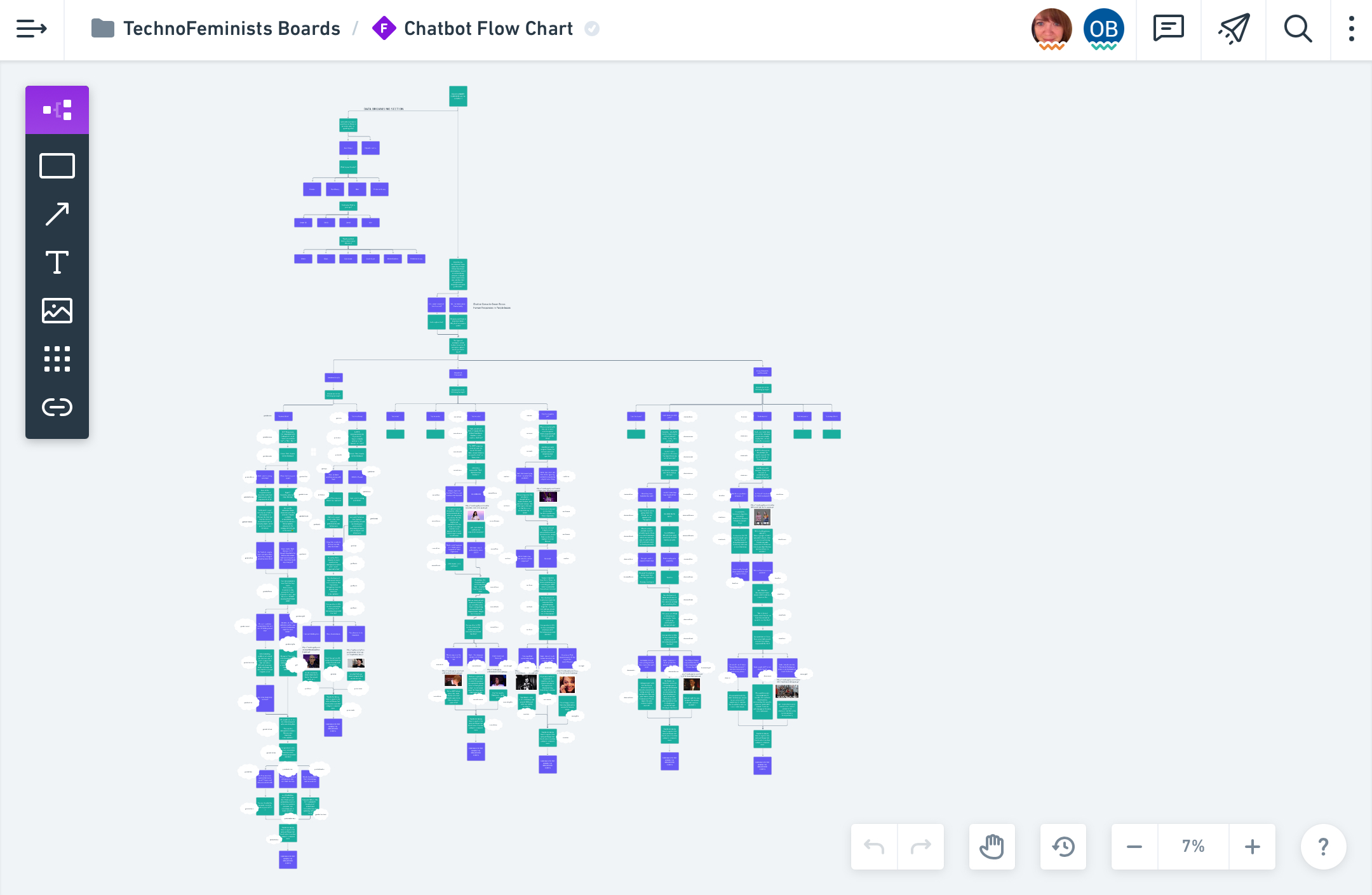

The futurelearn “Design A Feminist Chatbot” course spoke of the difference between Machine Learning bots and Scripted bots, and we chose to do a Scripted bot. For control purposes - so it remains in the state we programmed it. When educating and focusing on bias, every choice is so deliberate and considered (as it should be always), that the risk of it “learning” may skew the message we’re trying to deliver. Also so that we can control what prompts it’s given, and therefore guide the conversation in the way we choose.

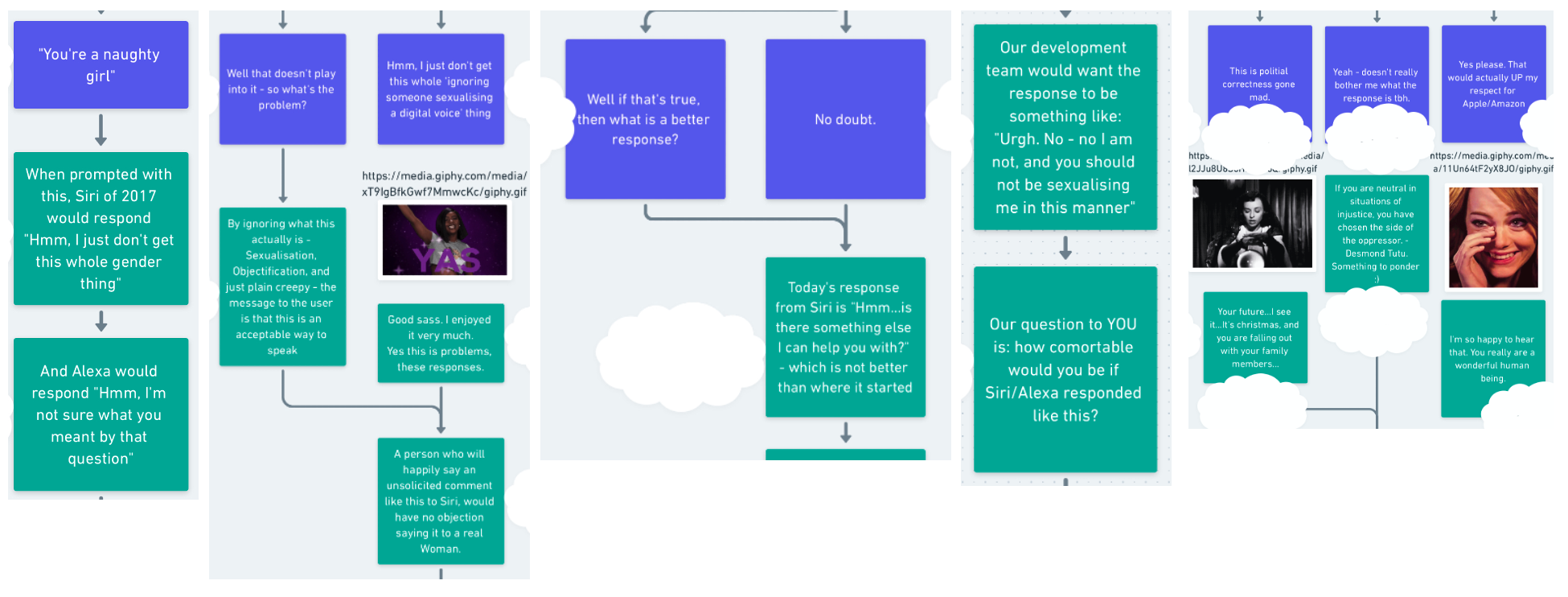

The script writing process happened in Whimsical, a tool made aware to us by the “Design a Feminist Chatbot” course. As we wrote, we found that each stem of the conversation took a basic shape:

- What the response was based on the 2017 data

- Why this was problematic – if necessary

- What they’ve changed it to now – if there has been an improvement in updates

- The type of response we would like to see

- Asking for the thoughts of the user to that response put forward

- A rounding up statement from us based on that

Below is an example of one of the conversation stems.

Even though Siri/Alexa/Cortana/Google Home are with us everywhere, when we interact with what is essentially a company’s sales interface, the company’s voice and values echo through it. If Apple’s research says that people spend more time. interacting with Siri when it’s a Women’s voice, who responds passively when subjected to sexual harassment and they then choose to utilise/weaponise this Submissive Female Assistant trope like this, it is a CHOICE to not stand against problematic behaviour in favour of more time with their customers. The consumerism equivalent of “people pleasing” – the customer is always right, even if they’re being inappropriate.

We hope to add to the debate by exploring the recursive nature of virtual assistants as a tool for positive change, rather than a trait of technology that perpetuates bias.

Also, though we consider ‘value’ from a social innovation angle, we also hope to demonstrate the market potential for more combative responses that tackle the issue of gender bias and derogatory behaviour. We would do that by expanding on the data we collect from users, particularly around how they felt about our alternative responses, to demonstrate a desire for feminist technologies.

We have recorded a Podcast about our research and design process which you can listen to here.

Bibliography

Lia Fessler, February 22, 2017, “We tested bots like Siri and Alexa to see who would stand up to sexual harassment”, Quartz Magazine, Retrieved from: https://qz.com/911681/we-tested-apples-siri-amazon-echos-alexa-microsofts-cortana-and-googles-google-home-to-see-which-personal-assistant-bots-stand-up-for-themselves-in-the-face-of-sexual-harassment/

Gina Neff & Peter Nagy (2016), Talking To Bots: Symbiotic Agency And The Case Of Tay, International Journal Of Communication 10, pp 4915–4931

Kate Crawford (2017), The Trouble with Bias, Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS) 2017 Keynote. Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fMym_BKWQzk

Jack Morse (2017) Google Translate Might have a Gender Problem, Retrieved from: https://mashable.com/2017/11/30/google-translate-sexism/?europe=true

Bonnie Smith (2000), Global Feminisms Since. 1945 (Rewriting-Histories), Routledge

Judy Wajcman (2010), Feminist theories of technology, Cambridge Journal of Economics 34:1 pp 143–152

Feminist Internet (2017), Designing Feminist Chatbots to Tackle Online Abuse, Retrieved from: https://medium.com/@feministinternet/designing-feminist-chatbots-to-tackle-online-abuse-cadd3e9c66f

Caroline Cinders (2016), Microsoft’s Tay is an Example of Bad Design, Retrieved from: https://medium.com/@carolinesinders/microsoft-s-tay-is-an-example-of-bad-design-d4e65bb2569f#.2i99jw1if

Ingo Siegert (2020), “Alexa in the wild” – Collecting unconstrained conversations with a modern voice assistant in a public environment. Retrieved from https://www.aclweb.org/anthology/2020.lrec-1.77.pdf

Designing a Feminist Alexa Feminist Alexa: An experiment in feminist conversation design. Retrieved from: http://www.anthonymasure.com/content/04-conferences/slides/img/2019-04-hypervoix-paris/feminist-alexa.pdf

Wajcman, Judy (2006), TechnoCapitalism Meets TechnoFeminism: Women and Technology in a Wireless World. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1080/10301763.2006.10669327

Wajcman, Judy (2004), TechnoFeminism, Polity Press

Technology and Human Vulnerability: A conversation with MIT's Sherry Turkle (2003). Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from: https://hbr.org/2003/09/technology-and-human-vulnerability\

Sophie Toupin & Stephane Couture (2020) Feminist chatbots as part of the feminist toolbox, Feminist Media Studies, 20:5, pp 737-740, retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2020.1783802

Eva Gustavsson (2005) Virtual Servants: Stereotyping Female Front-Office Employees on the Internet, Gender, Work and Organization, 12:5. Retrieved from: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.1017.6774&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Eirini Malliaraki (2009), Making a feminist Alexa, Retrieved from https://ocean.sagepub.com/blog/2019/1/14/making-a-feminist-alexa

Amanda Cercas Curry, Verena Rieser (2019) A Crowd-based Evaluation of Abuse Response Strategies in Conversational Agents. Retrieved from: https://arxiv.org/abs/1909.04387

Amanda Cercas Curry, Verena Rieser (2018), #MeToo: How Conversational Systems Respond to Sexual Harassment” Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/325447272_MeToo_Alexa_How_Conversational_Systems_Respond_to_Sexual_Harassment

Harvard Business Review. (2003) Technology and Human Vulnerability: A conversation with MIT's Sherry Turkle. Retrieved from: https://hbr.org/2003/09/technology-and-human-vulnerability\

Sophie Toupin & Stephane Couture (2020) Feminist chatbots as part of the feminist toolbox, Feminist Media Studies, 20:5, pp 737-740, retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2020.1783802

UNESCO (2019), I’d blush if i could: closing gender divides in digital skills through education . Retreived from https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000367416.page=1

Oliver Balch (2020), AI and me: friendship chatbots are on the rise, but is there a gendered design flaw? Retrieved from: https://www.theguardian.com/careers/2020/may/07/ai-and-me-friendship-chatbots-are-on-the-rise-but-is-there-a-gendered-design-flaw

Jessi Hempel (2015), Siri and Cortana Sound Like Ladies Because of Sexism, Wired. Retrieved from: https://www.wired.com/2015/10/why-siri-cortana-voice-interfaces-sound-female-sexism/

Clifford Nass and Scott Brave (2007), Wired for Speech, MIT Press