Do Nothing Club: The Always-on Culture and the Right to Rest

produced by: Marina Cardoso

Abstract

This research investigates the always-on culture and the attention economy in the 21st century and its consequences to the workforce, digital users and the general public. My interest in the theme came naturally since I am part of the system and I believe is a recurrent and relevant topic at the present time.

Always-on Culture

The attention economy I refer to is the capitalist nature that big corporations and tech companies use to monetise our time—or most precisely, our waking moment— by creating addictive design platforms and devices. The more we spend on these online systems, the more we scroll, like, share, watch adds, largest is the income for the companies. Wireless technology allows us to be connected from anywhere, at any time. Time became synonymous of consumption and our actions became commercial.

At the same time, Millenials are working more than any generation before. Workaholism is not a choice, though; it is driven by the fear of real consequences: to lose career opportunities, pay rent, not being recognisable. This is even more evident for freelancers or self-employees, as the distinction between work time and leisure time begin to fade away. This behaviour of always being available promoted by the capitalist industry strengthens the always-on culture, normalising working until late at night, at weekends, during vacation (when existing), and so on. Our value is now determined by productivity, and by productivity, I refer to the capitalist point of view. Every waking hour of our day is a time we could be working, being connected, monetising. The urgency and information overload from online media shape the non-stop nature of modern life.

Sleep Deprivation

As a result, we see a romanticized idea of working without pause or limits, life coaches promoting working as much as you can, while society experience increasing numbers on anxiety disorder and burnouts. We are sleeping less and later as we use to sleep. Insomnia and problems to sleep are now part of a daily basis. Drugs to sleep have never been so popular. We drink an unhealthy amount of coffee to keep us awake. The paradox is that, as shown in scientific researches, the less we sleep, the less productive we are.

The Fear of Missing Out (FOMO) culminate by modern life leaves us no time to rest, recharge, or think. Doing nothing, or doing any activity which cannot be monetising, are seen as useless. And if we allow ourselves to do it, we feel bad for not being productive. Jonathan Crary, in his book 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep, argues that "One of the forms of disempowerment within 24/7 environments is the incapacitation of daydream or of any mode of absent-minded introspection that would otherwise occur in intervals of slow or vacant time".

Corporations promoting productivity and competition on staff are the same relying on catching up words as well-being, mental health and self-care to create a false sense of support. Startups love showing up their "recharge rooms" and relax spaces, or their weekend retreat, occulting the real reason behind it: make employees more effective. Likewise, companies are offering flexible working hours and home office but increasing the workday length. In the same way, we see digital platforms, which are built-in addictive design principles, creating screen time limit tools to "help" the user make wiser use of their time.

Is interesting pointing out how "sleep mode" on electronic devices reflect this concept of never shutting down. Instead, they are working in a low power state.

Resistance

Before the industrial revolution, work shift was rooted in the diurnal cycle, meaning nighttime was equivalent to "stop working and going home". With the invention of electric lighting, this has changed, and people could work even late at night, denaturalising the organization of time. This validates the idea that rest is essential and part of human nature, or, as Arianna Huffington, author of The Sleep Revolution suggests, a right.

In 1817, tired of the ruthless 10+ working hours, British manufacturer Robert Owen led the Eight-Hour Day movement, which slogan was "Eight hours for work, eight hours for rest and eight hours for what you will". Today, the standard 8-hour workday has already been proved as ineffective, and some countries have reduced the workday hours to boost productivity.

The non-stop culture urges us to always be creating and producing something new at the same time that makes us impatient for anything non-commercial or poetic. The use of devices and/or apps for every human activity and the monetization of every aspect of our lives, in addition with the use of hostile architecture in public spaces —such as airports and park benches, to prevent people to use for sleep—, and private spaces (offices using uncomfortable toilets to avoid employees taking long breaks) reinforce our need to confront the cult of productivity and demand our right to rest. To quote Jonathan Crary again, "Sleep is the only remaining barrier, the only enduring 'natural condition' that capitalism cannot eliminate". Jenny Odell, the author of How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy, suggest we practice NOMO - Necessity of Missing Out.

Is important to have in mind that rest is a privilege; many workers can't afford to live near their workplace and have to wake up very early, spend hours on commuting, and at the end of the day come back to attempt to sleep in noisy and violent neighbours.

To be creative, we need time and space to be inspired. In other words, to be more creative, we need to be a bit unproductive (in the capitalist point of view). Many artists have been using the "doing nothing" motif onto their work. One of the most famous is Marina Abramovic's performance The Artist is Present (2010), in which the artist sits in a chair and make silent eye contact with strangers for a long period of time. In 4'33", John Cage surprised the audience with his silent play. Other examples adopt nature contemplation, as in Applause Encouraged (2015), by Scott Polach, and James Turrell’s Meeting (1980). To raise awareness of the addictive digital environments, Chris Bolin created The Disconnect, an online magazine that only works when you disconnect from wifi networks.

Artwork

Since for most of people is impossible to completely step away from the digital space, either because of work, studies, or network, my approach was to use this environment to make an intervention. The idea was to create a virtual space for people to rest, think, recharge, and/or do nothing. I chose to build a website for two reasons: First, I see it as a public and accessible medium; second, I wanted to involve my computational practice. The process to launch a website involves a lot of steps; for this project, given the experimental nature of it, I simplified the operation.

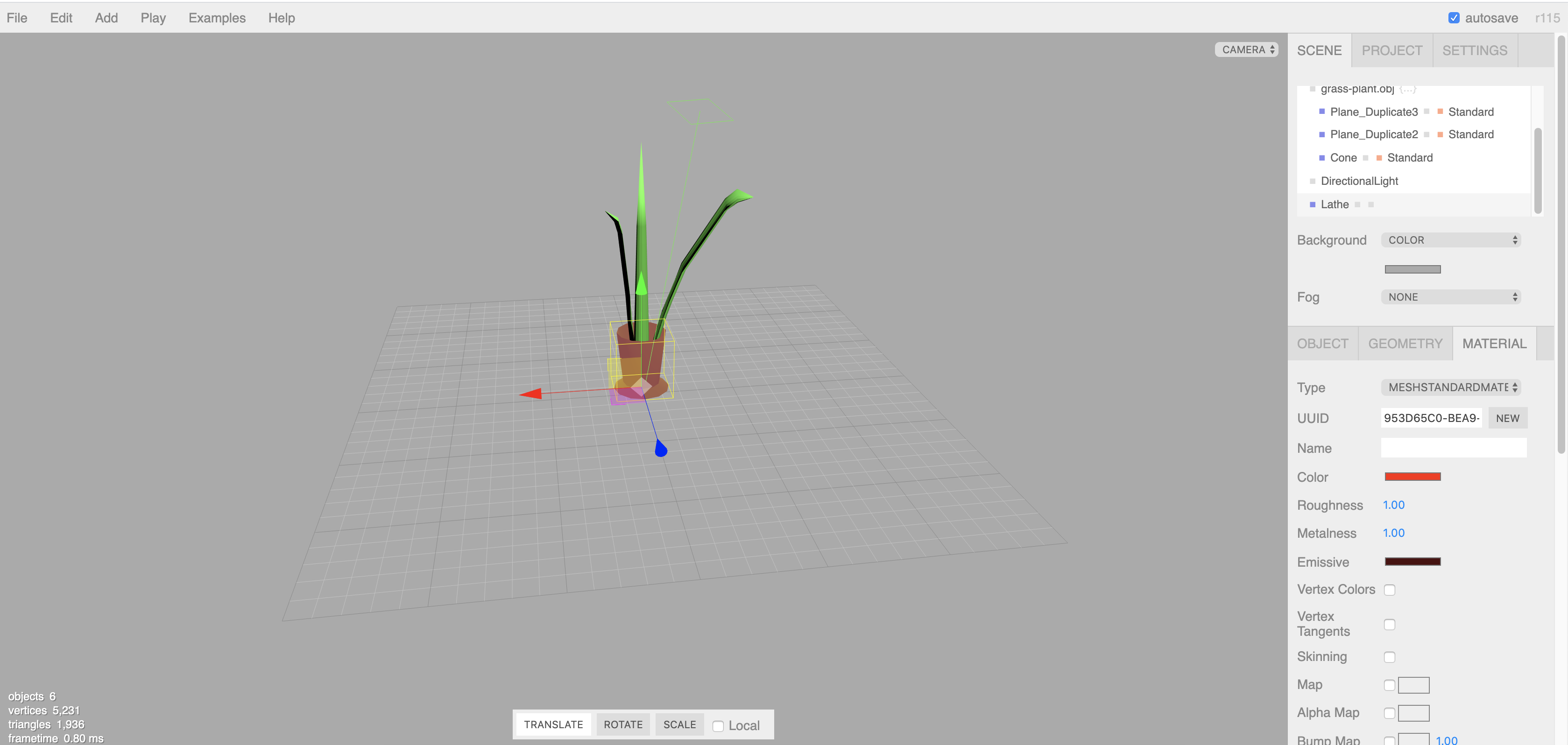

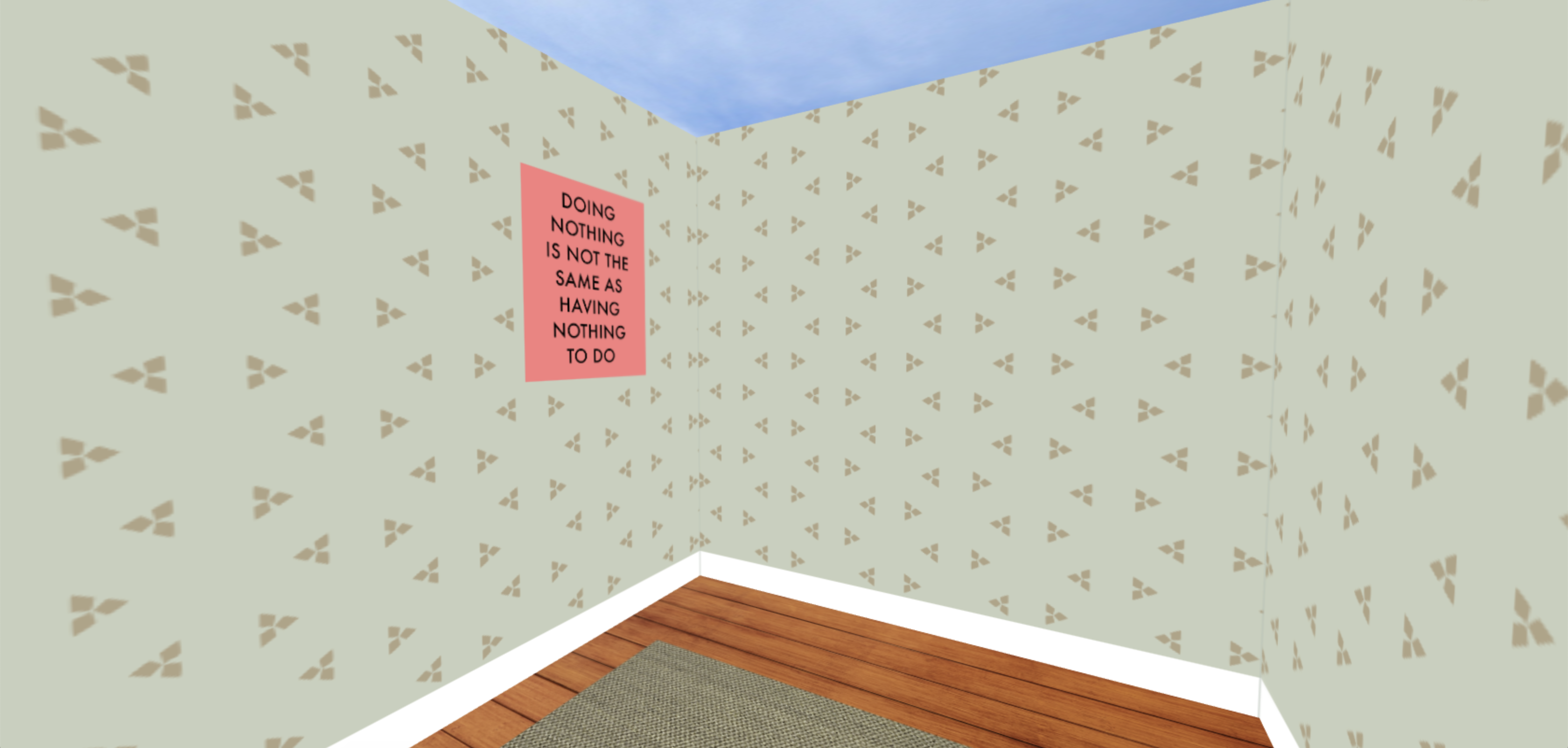

During my research, I came across a Javascript library for 3D graphics: Three.js. It allows you to model 3D shapes with code and implement them on web platforms. With Three.js it was possible to create a realistic 3D world. I wanted to create a place where people would feel relaxed, a space that transmits peacefulness. For many people, the living room is a space where they go when they want to settle back: Sit on the couch, watch TV, read a book, or play some music. I decided to create a virtual lounge with objects that are found in these spaces (sofa, rug, wallpapers, etc). First, I created the room with four walls and then added the objects.

Being in nature is often pointed out as a great activity to relax and inspire creativity, thus I added some elements of nature, such as the "sky roof"—a reference to James Turrell’s work Meeting—and a houseplant. I felt like a reminder of how these moments of inactivity are important should be included in the space. The poster in one of the walls reads "Doing nothing is not the same as having nothing to do". This phrase is one of the statements Douglas Coupland created for his work Slogans for the 21st Century. I thought was a good idea to include interaction, in which users could use the mouse to navigate for all the angles of the room. The last thing was to add a piece of calm music to play when the website is opened.

The second part of the website-artwork development was to choose and buy a domain and find a hosting service. I thought "do-nothing.club" was a decent name because it is easy to remember and type, and the "club" ending is somehow an indicator of a group of people, working as a request for people do the same (access the website). For the hosting I used Netlify, a simple and easy to use free hosting service.

I had some obstacles during the code development as I'm new to the Javascript language and the Three.js library. Even with the available documentation, examples and video tutorials, I was dealing with constant bugs and errors, some of them I couldn't solve yet. However, given the project production time, I am satisfied with the final results. I've decided to use the Critical Technical Practice method for the research, as I consider this artwork a disobedient object. With this website, I want to communicate a larger issue, the right to rest and step away from the attention economy.

Conclusion

When people access the website, I expect they have a brief moment of relaxation and self-care, at the same time refusing the idea of non-stop productivity that the modern world promotes. This website is a public, non-commercial space for anyone who wishes to take a break but doesn't want to put in their attention on social media platforms or tech companies that monetise their time.

Sleep and rest became a luxury in modern society, but we should not forget it is a basic necessity of human being. We must claim our right to pause, especially at work. I hope this website contributes to raising awareness of the need to rest and the ways we spend our attention. Furthermore, make the internet more mindful and human: Fewer ads, less distraction, more creativity.

Annotated Bibliography

1. Crary, J. (2013). 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep. London: Verso.

Jonathan Crary is an American art critic and teacher at the University of Columbia, New York. In this book, he investigates the term "24/7" and the attention economy, what he calls the "non-stop world". Written as an essay and divided into four chapters, Crary approach themes such as the origins of Capitalism —from Industrial Revolution to the present days—, the Technological Evolution, the interrelation between work and everyday life, and the analysis of the modern economy with the act of sleep (or the lack of it).

2. Odell, J. (2019). How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy. Brooklyn, NY: Melville House.

Jenny Odell is an artist and educator living in Oakland, California. This book, which is based on her talk of the same title, undertake ways in which technology use addictive features to take our attention and make us live in a constant condition of fear and anxiety. Through histories and examples from her own experience, she invites us to rethink our role in the modern economy, proposing a "step away" as an act of resistance and reconnection with our surroundings, local ecology and people.

3. Coupland, D., Obrist, H. and Basar, S. (2015). The Age of Earthquakes: A Guide to the Extreme Present. Great Britain: Penguin Books

Hans-Ulrich Obrist, the famous art curator and artistic director of Serpentine Galleries, Shumon Basar and artist Douglas Coupland joined with several artists and designers to create this book, written as a collection of quotes and questions about the modern world, internet, data, technology, time, and future. The title "age of earthquakes" is a metaphor for a time of world conflicts, instability and polarisation. This provocative book is an artwork itself, each page containing a mixture of images, emojis, illustrations and collages to represent the information abundance of our digital era.

Reference List

Groopman, J. (2017). The Secrets of Sleep. [online]. Available at: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/10/23/the-secrets-of-sleep [Accessed 30 March 2020]

Morris, B. (2016). Arianna Huffington’s Sleep Revolution Starts at Home. [online]. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/01/realestate/arianna-huffingtons-sleep-revolution-starts-at-home.html [Accessed 9 March 2020]

Raphael, R. (2017). Netflix CEO Reed Hastings: "Sleep Is Our Competition". [online]. Available at: https://www.fastcompany.com/40491939/netflix-ceo-reed-hastings-sleep-is-our-competition [Accessed 27 March 2020]

Tolentino, J. (2017). The Gig Economy Celebrates Working Yourself to Death. [online]. Available at: https://www.newyorker.com/culture/jia-tolentino/the-gig-economy-celebrates-working-yourself-to-death [Accessed 8 April 2020]

Torres, M. (2019). This Toilet Patent Makes Workers Uncomfortable Taking Long Bathroom Breaks. [online]. Available at: https://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/entry/toilet-design-long-bathroom-break_l_5dfa5ff0e4b018347919ec4d [Accessed 9 March 2020]

Vieira, W., and Vila Nova, D. (2020). O Que Aconteceu Quando o Celular Invadiu a Sua Vida Profissional?. [online]. Available at: https://gamarevista.com.br/semana/defina-trabalho/celular-trabalho-pandemia/ [Accessed 8 April 2020]

Wade, L. (2019). The 8-Hour Workday Is a Counterproductive Lie. [online]. Available at: https://www.wired.com/story/eight-hour-workday-is-a-lie [Accessed 29 April 2020]