Dirge

THRENODY FOR THE VICTIMS OF ANTHROPOCENE

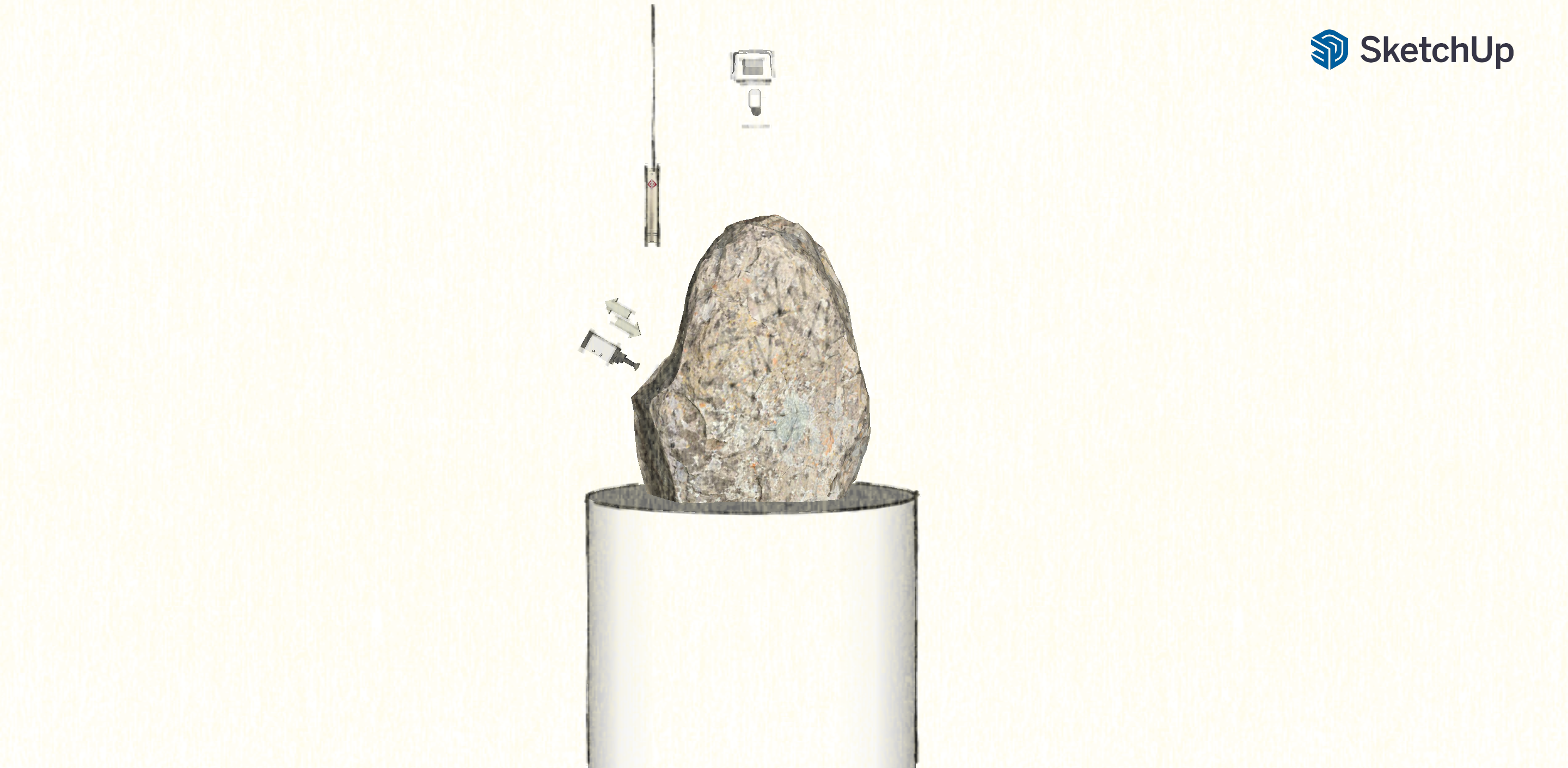

interactive multi-media installation sketch and proof of concept

by Lucie Stepankova

The moment you enter, you are immersed in a sorrowful song of a weeping rock.

It is not long before the cries die out as you begin your approach, your gaze turned toward it.

You are intrigued but also terrified by the intricate system of now dormant devices surrounding this dignified relic.

The ancient artefact which doesn’t belong within these walls.

You are being watched, your presence scrutinized, your decisions judged.

What to make of this most unlikely assemblage?

Sooner or later, you will turn your gaze away and the rock will lament again.

Now you know that your indifference is the cause for its suffering.

What do you choose to do next?

INTRODUCTION

“AN ENCOUNTER IS AN EVENT OF RELATION – IT IS ABOUT TWO BEINGS OR THINGS THAT ARE MOMENTARILY HELD TOGETHER. ENCOUNTERS MAKE (A) DIFFERENCE […] AND ARE OFTEN EXPERIENCED AS SOMETHING THAT DISRUPTS, UNSETTLES, OR SURPRISES IN WAYS THAT CAN BE AS AFFIRMATIVE AS THEY CAN BE VIOLENT.” (WILSON, 2019)

This is a proof of concept treatise and a sketch of an interactive multi-media installation exploring transformative encounters through experiencing discomfort. In the installation, the participants are individually or collectively encountering and interacting with the artefact - a rock on a plinth, four solenoid engines, four microphones, a surveillance camera and four speakers. Once in the gallery space, there is no escape from having to face the centerpiece of the artefact or be subjected to the consequence of not doing so, all the while being scrutinized by the all-seeing-eye of a surveillance camera.

There are several discomforting elements at play in this work. Firstly, the uncanny sound (Toop, 2016) which here carries stories revealing denial of uncomfortable realities and with it the risk of acknowledging our part in their making. And secondly, the menacing sensation of being watched, judged and made to feel responsible for taking part in unleashing those realities. While seeing is a form of witnessing generally portrayed as the most credible it doesn’t necessarily allow us to access beyond the threshold of what is being depicted. On the other hand “[w]hat the ear perceives is not the unified and perspective space of the eye, but multidimensional space-time which is dominated by simultaneity and movement.” (Hauk, 2015) Seeing is concrete and listening is labyrinthine. It accommodates potentialities (Voegelin, 2017) and “can be immersive, resonant, lending learners to relational and multispecies sensing.” (Hauk, 2015) I often come back to Salome Voegelin’s Sonic Possible Worlds (2017) when thinking about sound as a carrier of more than just acoustic information. Voegelin and Hauk both champion belief in sound that carries intelligence beyond the audible. Of course, sound possesses an undeniable physicality, but it is those veiled potentialities that bear significance and give purpose to this work. Sounds have the potential to transmit emotions (Hauk, 2015), describe spaces, illuminate catastrophes.

In this way Dirge becomes a metaphor for catastrophes that exist at - space and time - scales unavailable to our perception (Morton, 2014). In the context of this assemblage (Tsing, 2015) of the rock, the surveillance technology and the human presence mingling within the gallery space, Dirge becomes a downscaled model of larger assemblages - hyperobjects (ibid.) - that exist in flux within and around us - the micro-organic material composition of our bodies, the environment, the society. This work loosely explores in particular two of the latter as it aims at cultivating “willingness to ‘inhabit a more ambiguous and flexible sense of self’ (Boler, 1999, p.176), to step out of one's comfort zone, question how one might be implicated in the lives of others, and draw attention to both connection and separation.” (Wilson, 2020)

THE ARTEFACT

The central focal point of this installation is a large piece of rock placed on a pedestal within a gallery with a live-feed CCTV camera fixed above it facing the space. The rock is surrounded by an arrangement of four solenoids connected to a microcontroller receiving data from a custom C++ face recognition software. The camera captures real-time visual data that are analysed within the software and sent as commands to the microcontroller. If a face is present - the participant is facing the rock - the solenoid arrangement remains static. If a face is not present - the participant turns their gaze away from the rock - a signal is sent to the microcontroller and the solenoids start moving, poly-rhythmically chipping away at the rock’s body. These sounds are captured by four high-sensitivity microphones and amplified within the space through an arrangement of four speakers.

The work can be experienced both individually and collectively with each of the experiences having their particular attributes. When a single individual encounters the artefact, the experience is an intimate one, the weight of responsibility resting solely on their shoulders. When experienced collectively, the participants become a part of a social experiment in which they are forced to make a collective decision, interacting not only with the artefact but with each other too. When more than one participant occupies the space, a custom function calculates and returns three values - total number of participants, number of participants facing the artefact and number of participants not facing the artefact. In case more than half of the participants are facing the artefact, the solenoid engines are static. In the opposite case, the solenoids become animated.

In both instances, participants engage in an encounter that transforms the way they relate to and interact with the non-human, particularly in relation to ethics (Wilson, 2019).

CONCEPT

“WE ARE NEVER IN A STATIC ‘RELATION TO’ SOMETHING, BUT IN A CONSTANT FLOW OF RELATION, AN IMMERSION WITH A WORLD WHICH IS ITSELF VIBRANT AND SUBJECT TO ALTERATION, DIFFERENTIATION AND ENDLESS VARIATION. IN THIS SENSE, OUR ENCOUNTERS ARE NOT MERELY WITH THE WORLD, BUT ARE OF THE WORLD: MOMENTS OF CONTACT IN THE PRESENT THAT OPEN UP TO THE UNFOLDING AND SHIFTING REALITY OF THE THINGS AND LIVES WE MEET.” (TODD, 2020)

Dirge: Threnody for the Victims of Anthropocene as a title hints to the poignant nature of the work and as such relates in general terms to a deeply felt expression of grief. The sub-title’s reference is to Krzystof Penderecki’s 1960 composition for 52 string instruments - Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima - dedicated to those who died during the Hiroshima bombings in August, 1945. The severe nature of this reference is in line with the essence of the work in as much as it helps illustrate the devastating power of human indifference in a very concrete way. Indifference which is one and the same when it concerns human impact on the environment and for the purposes of this work equals anthropocentrism.

This work seeks to raise awareness about and criticise this cataclysmic attitude towards the world and the beings and things forming and inhabiting it. It does so by staging a discomforting encounter that unsettles and for that reason is “invested with transformative potential, for the process of unsettling creates openings.” (Wilson, 2020) Openings understood as possible catalysts for “[s]ensing, listening, intimate observing, imagining, feeling, entangling, and wondering [that] can shift unsustainability epistemologies and transform human and cultural engagement with […] the world.” (Hauk, 2015) The fact that we are unable to fully perceive the impact of anthropocentric attitudes doesn’t make it any less real. Our current predicament is a slowly simmering catastrophe that outgrows by lightyears in scale the atrocities of Hiroshima if we do not reevaluate our ways. This “calling into question […] is brought about by the other. We name this calling into question of my spontaneity by the presence of the Other, ethics.” (p.43) The first step to rethinking is inescapably encountering beings and things revealing that which we are not aware of or which we chose to deny or ignore. The purpose of this installation piece is to trigger this process of rethinking and moving towards multi-species (Hauk, 2015) ethics.

I have chosen the approach of staging encounter (Tsing, 2015) through discomfort for its powerful transformative potential. Transformative encounter through discomfort is a term borrowed from theoretical discourse on social justice and environmental education outlined and explored by Boler (1994), Hauk (2015), Wilson (2019 & 2020) and Todd (2020), among others. Notably, “Boler (1999, p.200) […] describes a pedagogy of discomfort as an invitation to engage in critical (and discomforting) processes that ‘question cherished beliefs and assumptions", especially those that have been shaped by dominant cultures or ways of thinking. A pedagogy of discomfort, as she put it, is an invitation to ‘live at the edge of our skin’ (ibid).’” (Wilson, 2020)

Like Latour (in Todd, 2020, p.1122) I believe that aesthetic experiences are “what renders one sensitive to the existence of other ways of life” and so they are in a sense pedagogical. Todd (ibid.) asserts that “[w]hile the work of the teacher carries with it different responsibilities, it also echoes the installation artist's considerations as it too stages encounters between students and elements in the environment.” The artist here assumes the role of a teacher facilitating a rupturing face-to-face encounter (Levinas, 1969) in a form of an immersive experience. Such experiences are more adequate than ordinary language in telling about suffering (Padfield and Zakrzewska, 2021, p.38) and can render “us sensitive to the shape of things to come.” (Latour, in press; in Todd, 2020, p.1122) The language I use is an amalgam of sensual and emotional and I am the facilitator of the participant’s transformative encounter with a rock.

ROCK AS THE SUFFERER OF PAIN.

ROCK AS THE “STORYTELLER OF PAST CLIMATE, LIFE AND MAJOR EVENTS AT EARTH’S SURFACE.” (COLSON, N. D.)

ROCK AS “A TEMPORAL BEING, AN ENTITY SHIFTING AND CHANGING IN TIME, ALTHOUGH THE RHYTHM OF ITS CHANGES MAY BE FAR SLOWER THAN MY OWN.” (ABRAM, 1997, P. 40)

ROCK AS SOLID YET NOT INVINCIBLE.

Like everything else, rocks are assemblages of matter particles held together by physical forces, animated by what Jane Bennett (2010) calls thing-power. “To the sensing body all phenomena are animate, actively soliciting the participation of our senses, or else withdrawing from our focus and repelling our involvement. Things disclose themselves to our immediate perception as vectors, as styles of unfolding – not as finished chunks of matter given once and for all, but as dynamic ways of engaging the senses and modulating the body.” (Abram, 1997, p. 56). This is to say that rocks are fragile animate entities yet their vulnerability exists on a different spectrum than, for example, that of dew drops. At one point they too give in, give up, break down.

Here, a small army of solenoid engines are engraving ominous messages into the rock and it is only up to the participants to make them stop. They are made to witness either the haunting sculptural form merging natural bodies and technological artifacts (Bennett, 2010) or experience the agony reverberating through the space. A sonic metaphor for something much bigger than this particular rock, this particular participant cohort and their shared experience within this particular space. Hauk (2015) recognizes the capacity of “[a]ural sensing [which] connects the learner to inner and outer information from the complex living systems within which the [..] learners are immersed, and which they themselves are co-generating” while Padfield and Zakrzewska (2021) add that by witnessing “the pain of others [we] can advance a true acknowledgment of experienced suffering.” (p.34) Not only are the participants subjected to the multi-sensual and - in extent - emotional aspects of the work, they are being watched, their presence, decisions and interactions scrutinized by the all-seeing-eye of a surveillance camera. This complex amalgam of the sensual and emotional can - and hopefully will prove to - be discomforting and rupturing in ways that make the participants question their engagement with the world and that will nurture and sustain compassion, inspire reflection and willingness to reevaluate, and most importantly, to act.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Abram, D. (1997). The spell of the sensuous: perception and language in a more-than-human world. New York: Vintage Books.

Abram, D. (2017a). Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology. Tantor Audio.

Bennett, J. (2010). Vibrant matter: a political ecology of things. Durham: Duke University Press.

Boler, M. and Greene, M. (1999). Feeling power: emotions and education. New York ; London: Routledge.

Branzi, A., Giulio Ceppi and Al, E. (1998). Reggio children: children, spaces, relations: metaproject for an environment for young children. Milan: Domus Academy Research Center.

Coates, M. (2013). Unmade Monument. Available at: LINK [Accessed 4 May 2021].

Colson, R. (n.d.). EST-Rocks and fossils. [online] web.mnstate.edu. Available at: LINK [Accessed 22 Apr. 2021].

Haraway, D. J. (2008). When species meet. Minneapolis: University Of Minnesota Press ; |A Bristol.

Haraway, D. (2016). Staying With The Trouble: Making Kin In The Chthulucene. Durham (N.C.) ; London: Duke University Press.

Hauk M., et al. (2015). Senses of Wonder in Sustainability Education, for Hope and Sustainability Agency. [online] The Journal of Sustainability Education. Available at: LINK [Accessed 20 Apr. 2021].

Hooks, B. (1994). Teaching to transgress: Education as the practice of freedom. Routledge.

Kearns (2015). Subjects of Wonder: Toward an Aesthetics, Ethics, and Pedagogy of Wonder. The Journal of Aesthetic Education, 49(1), p.98.

Lapworth, A. (2013). Habit, art, and the plasticity of the subject: the ontogenetic shock of the bioart encounter. cultural geographies, 22(1), pp.85–102.

Latour, B. (2017). Facing Gaia: eight lectures on the new climate regime / Bruno Latour. Polity: United Kingdom.

Lévinas, E. and Lingis, A. (1969). [Totalité et infini.] Totality and infinity. An essay on exteriority ... Translated by Alphonso Lingis. Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press ; The Hague.

Merleau-Ponty, M. (1968). The Visible and the Invisible. Evanston, Ill: Northwestern University Press.

Morton, T. (2014). Hyperobjects : philosophy and ecology after the end of the world. Minneapolis: University Of Minnesota Press.

Morton, T. (2019). Humankind : solidarity with non-human people. London ; New York: Verso.

Oliver, J. and Vu, C. (2017). The Extinction Gong. Available at: LINK.

Padfield, D. and Zakrzewska, J., (2021). Encountering Pain. London: UCL Press.

Penderecki, K. (1960). Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima.

Pratt, M.L. (2008) Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation, 2nd ed. London: Routledge.

Selby, D. and Kagawa, F. (2015). Sustainability frontiers: critical and transformative voices from the borderlands of sustainability education. Opladen: Barbara Budrich Publishers.

Tate (n.d.). Andy Goldsworthy: “We share a connection with stone” – TateShots. [online] Tate. Available at: LINK [Accessed 22 Apr. 2021].

Todd, S. (2003). Learning from the other: Levinas, psychoanalysis, and ethical possibilities in education. Albany: State University Of New York Press.

Todd, S. (2020). Creating Aesthetic Encounters of the World, or Teaching in the Presence of Climate Sorrow. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 54(4), pp.1110–1125.

Toop, D. (2016). Into the Maelstrom: music, improvisation and the dream of freedom. Before 1970. New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

Tsing, A. L. (2012). Unruly Edges: Mushrooms as Companion Species. Environmental Humanities, [online] 1(1), pp.141–154. Available at: LINK.

Tsing, A. L. (2015). The mushroom at the end of the world: on the possibility of life in capitalist ruins. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Voegelin, S. (2017). Sonic possible worlds: hearing the continuum of sound. New York Etc.: Bloomsbury.

Wilson, H.F. (2019). Contact zones: Multispecies scholarship through Imperial Eyes. Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space, 2(4), pp.712–731.

Wilson, H.F. (2020). Discomfort: Transformative encounters and social change. Emotion, Space and Society, 37, p.100681.