Collaborative, destructive music editing in a Post-Internet age

Harry Morley

Basis

This project is a report of a personal journey and a reflection into a simple composition process carried out as an investigation into creativity, postphenomenology and Post-Internet theory. The process involves sending simple stereo files back and forth with a friend over instant messaging, to develop a piece of music, as opposed to using a real-time system or multi-track file transfers (‘stems’) for remote collaboration.

I aim to explore what it means to actively use a destructive technique like this in a world where non-linear is now the fashion, through a postphenomenological lens, and thinking with an “Internet state of mind” (Archey and Peckham 2014, p8). So the research has driven the artefact, the artefact has driven the research. Where much academic discussion has focussed on the here and now with computers, the immediacies, intimacies and development of computers in the music making process, I would like to step in a different direction, and focus on the relations between collaborators and their mediators, when the process is somewhat banal. Unlike the destructive nature of the artefact’s editing process (which I will describe later), I intend this paper to have a non-destructive personality.

Constraint

The moment the computer is involved, we are stunned with the Turing completeness of our computer and the possibilities of sound that can be computed endless. A piece of music, especially in its digital form, can be viewed as one high dimensional point, atom or existence discovered in a sea of endless possibility. I found that Adam Harper has a similar approach to describing music as a complex system of variables, sonic or otherwise, situated in a space that can be explored (2011, p36). The one difficulty of this reality is the phenomenon ‘option dilemma’, which refers to “the compositional paralysis caused by the overwhelmingly open design space provided by computer-music systems.” (Duignan et al 2010, p31)

Similar ideas are echoed by Simon Reynolds in his Pitchfork article Maximal Nation:

“Digital technology makes the artistic self at once hollow (buffeted by torrential, every-which-way flows of influence) and omnipotent (capable of molding sound and melding styles at will).”

He goes on to discuss recording artist Matthew Ingram’s view on contemporary music software usage:

“[He] wrote about how digital audio workstations like Ableton Live and FL Studio encourage ‘interminable layering’ and how the graphic interface insidiously inculcates a view of music as ‘a giant sandwich of vertically arranged elements stacked upon one another.’ Meanwhile, the software's scope for tweaking the parameters of any given sonic event opens up a potential ‘bad infinity’ abyss of fiddly fine-tuning.”

To overcome these issues, waypoints in this infinite sea must be defined in order to navigate from A to B, by putting in place or utilising existing constraints. In the words of Margaret A. Boden, “Constraints map out a territory of structural possibilities which can then be explored, and perhaps transformed to give another one.” (2004, p95). My destructive process for collaboration aims to interrupt the endless cycles of tweaking and layering by forging new sounds and driving the process forward.

Constraints, according to Linda Candy, can be both negative and positive. Taking the positive, they could be beneficial “because they have either been self imposed or have arisen from the intrinsic characteristics of the work itself” (2007, p366). Having self-imposed constraints lends a feeling of control and steering, but I am interested in the aforementioned ‘intrinsic characteristics’. With regards to material we worked with, the sonic characteristics were that of a kind of aging over time, and a build up of digital artefacts due to the editing process.

Destructive editing

In a world currently dominated by visual histories, undos, or, with a popular culture currently obsessed with looking backwards, a destructive approach may be able to provide a refreshing alternative. Firstly, taking a look at the other side, non-destructive editing individualises the elements of the composition and spawns links between them, or, places lenses over them, so that we may hear them differently. The digital information about the original sound objects remains intact.

With destructive editing, there is no going back, unless copies are made (I do not by any means intend to regiment a practice of never going back - of course, it may be required if a mistake is made, and these days there are virtually no space limitations when making copies: storage can always be increased). However, when mixing down parts to a single stereo file, sounds with common positioning in time are made into a single tangible object (like an irreversible mixture), and is up for remixing. This allows for the manipulations of high level abstractions (Duignan et al 2010, p31) at the expense (and progressiveness?) of losing low level control: one is forced to work with the material in hand.

When control is lost through the rendering (or ‘bouncing’) of an audio file, how might we work with what we have and how might this be beneficial to understanding the music? Well, in the words of Trevor Pinch, “Ihde teaches us to pay attention to the meaning given to sound in particular contexts - there is no meaning outside of context or use” (in Selinger 2006, p50) and to quote Ihde, “In all music, sound draws attention to itself. This is particularly the case in wordless music, music that is not sung. Here the ‘meaning’ does not lurk elsewhere, but is in the sounding of the music” (Ihde 2007, p155). Thus the self-referential aspect of a composition is highly important, and we must listen and pay attention to what the sound is telling us in order to know what to do.

In the case of the artefact (introduced very soon) and its musical style (key words: textural, wordless, instrumental, experimental), the context of the piece is itself, and this self-referentiality presents itself as a sculpture to shape - it is, as Ihde puts it, “a dense embodied presence” (2007, p155). The shaping process could be regarded as a phenomenological journey, as one acts on the sounds depending on how they are introspectively experienced.

Post-Internet age

Michael Waugh (2017) draws from Jurgenson (2012) by making clear that there is not much separation between virtual and physical spaces. When digital technologies are criticised as being intrusive and a distraction, we are told to log off and disconnect once in a while. By saying this, it assumes that one goes to a different, less real place when using digital technologies, when in actual fact, “the Post-Internet era is defined by the lack of difference between being online and offline”, or in other words, it is all real life.

Regarding the 'back and forth’ compositional process, I think it would be wrong to class this as a pre-Internet or pre-digital method. The concept is similar, but I believe the results are influenced by the experience of being online, even if the collaboration is not performed in real time. Faster-than-ever Internet speeds, the experience of instant messaging, and a common goal to achieve musical output seems to shorten the distance between collaborators.

While artists such as Holly Herndon attempt to make audible the daily digital experiences of the Post-Internet creature, such as web presence, connectivity and surveillance (as outlined by Waugh, 2017) and more recently the dawn of AI realism, my process took a different approach to exploring Post-Internet themes. The result is a sonification of the relations between two nodes on a network, and through destructive means (could this be accelerationist?), compositions are produced as a continuous effect of being online with one another.

Collaborating over the Internet ‘feels’ different to other, physical means. Firstly, there is a simultaneous sense of being with and not with the other. There is no separation, as Waugh says, “between the identities of Post-Internet users online or offline, with each informing the other constantly” (2017, p236). Waugh goes on to explain that these virtual spaces are “so ubiquitous, that they must be considered part of the ‘real’ world.” (Ibid., p235). Secondly, there is a sense of flow when sending files to one another. The productivity is surprising and rewarding because the result emerges through virtual means. This reminds me of the McLuhanian concept of the ‘electric’ era that Ihde writes about (2007, p232):

“In an ‘electric’ era we model our minds on the electric computer…”

Loosely, these are the models of long/short term memory, input and output, brain as primary information processor, to name a few.

“The ‘electric’ world is a world of ‘flow’, its images are suggestive of transmutation, transformation, and the melting of distinction. In music, again particularly among youth, the whine and microtonic ‘flow’ of the sitar and the ‘electronic instruments’ ‘infinite flexibility’ embody the flow of the electric.”

It is this concept of flow that I was trying to harness by employing the destructive process, in order to create the composition.

---

As Holly Herndon said at her talk at Ableton Loop in 2016, “the laptop is the most intimate instrument that we’ve ever seen” (Ableton, 2016). This is because of the way it mediates all of our daily experiences. As well as the immediate intimacy with laptops, I think that the closer we get to them, the more intimately they may mediate our creative experiences with other people. The idea that embodiment emerges with a high degree of intimacy is expressed by Young (2010, p2), albeit in the context of performance and improvisation. I think that this can be applied to composition too, making the laptop reach out to the other person’s laptop over the network, forming a kind of 'alterity relation' (using a postphenomenological term from Rosenberger and Verbeek, 2015).

Artefact

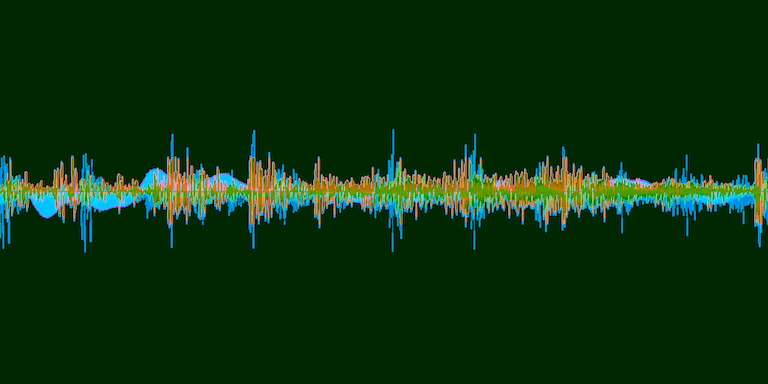

Six pieces demonstrating the iterative, destructive music making process. The final track [3b] is intended to be heard as the final reincarnation of the piece, thus the final artefact. All ideas recorded before it still exist within it, but perhaps gaseously and in spirit. All six versions are included to tell the whole story. As you can hear, elements from the previous iterations are brought forward into newer ones, and they make serious twists and turns along the way, sounding ever more digital and online.

I began by creating a piece of music using my Digital Audio Workstation of choice, Ableton Live, and various software synthesizers and samples. I assumed a collaborative mindset and created not just for myself, but the piece of music and my collaborative partner. When I felt like I had said enough for now, I ‘bounced’ the project down to a stereo .wav file and sent it, via instant messaging, to my friend. He then took the file with his own choice of software and hardware, edited it, added to it, removed from it, until he felt like he had said enough for now. This process occurred three times (or ‘passes’) in total, resulting in six files produced by either me or him. Every time, we treated the file as new content from which to work from, and at the same time as a story to continue telling.

To use Gil Weinberg’s (2005) theoretical framework for networked collaboration, this method uses the server approach: “This simple approach uses the network merely as a means to send musical data to disconnected participants and does not take advantage of the opportunity to interconnect and communicate among players.” But where this refers to a perhaps older method of doing things, mine is more aware of its connection between collaborators. Speculatively thinking, I envisage the artefact as 'living' amongst the communication that occured during our IM conversation, when we discussed editing the track.

For this particular experiment, we kept to a strict, linear process where we would only work on the previous iteration. Of course, during the participant’s creating and editing session, non-linear and non-destructive techniques could be employed, depending on what the preference is there (i.e. multi-tracking, triggering loops, layering more content, applying effects). But once finished, the piece is rendered to a single stereo .wav file.

Both of us primarily used our laptops as the primary instrument for composition - I sampled a synthesizer a few times, but mainly, we worked with samples, software synths, effects and Max4Live plugins. Therefore the artefact, having been conceived from two intimate laptop scenarios, has been made to sound like it belongs in this setting - between two, existing online. I would call the artefact a kind of ‘Internet music’, which, as Adam Harper puts it, is “not just music on the internet, but music heard as being shaped by, symptomatic of, or straightforwardly 'about' the perceived effects of the internet, with the two often conflated” (2017, p87).

I intended the concept of the artefact to be audible - such that the destructive process presents itself, as the piece morphed into new pieces. I quote Herndon again, this time when she asked the question, “How can the concept of a work inform the production of a piece to the extent that its actually audible?” (in Ableton, 2016) The piece has a voice, comprising many voices built up in an additive manner. Analysing briefly the sonic qualities of the pieces, I think that the production sounds like the concept in the following ways:

- Heavily sample-based

- Inherently digital effects (bitcrush, hollow sounding reverb)

- Cut up samples, obfuscated words, made unclear by glitchy effects

- Striated textures

Reflection

During the course of this project, I have researched different ways of thinking about a particular compositional practice - that of destructivity - through Post-Internet and postphenomenological means. It has been a theoretical encountering with a way of working that I am familiar with, and I am interested in the way certain ideas have presented themselves - for example, the way the sound of the piece has changed over time, and how it has affected my creativity.

Another angle to explore, is finding new possibilities for collaborative, asynchronous music creation, now I have used this simple method as a starting point. I would like to investigate new user-interface designs for DAWs, ones that can lessen the distinction between linear and nonlinear representations of time, at any stage in the creation process.

I also think there is more to research into specifically postphenomenology and composition, and the experiences that can occur during this process. It differs slightly from live performance, because the editing process is ongoing and the composition experience is not as ephemeral. Though the compositional exercise was simple and it could be seen as an archaic way of working, I believe there will always remain a place for this destructive, asynchronous approach, as the transactions of collaboration can occur through the fast medium of a typical instant messaging conversion. Working in this manner is an easy way to achieve a feeling of working within a virtual space, which may be desirable.

Meditation

THE ARTEFACT

IF AN ORGANISM

HAS BEEN ON MANY JOURNEYS

THROUGH CYBERSPACE

IN A STEREO

EVER-GROWING FORM.

WE GAVE IT RESIDENCE

IN OUR VIRTUAL CONVERSATION

THERE IT HEARD US

IT GREW AND LEARNT

WE HELPED IT ALONG ITS WAY.

TEXTURES EMERGE AND SUBMERGE

LIKE THOSE WOVEN PATTERNS

I REMEMBER FROM THE WOOLLEN MILL

ON FAMILY HOLIDAYS

MANY YEARS AGO.

Bibliography

Ableton, n.d. Holly Herndon on process | Loop. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6baj34lxF4g

Archey, K., Peckham, R. 2014. ‘Art Post-Internet: INFORMATION/DATA’. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/51a6747de4b06440a162a5eb/t/5ab019a9aa4a99dde60bdd5a/1521490402725/art_post_internet_2+%281%29.pdf

Candy, L., 2007. Constraints and Creativity in the Digital Arts. Leonardo 40, 366–367. https://doi.org/10.1162/leon.2007.40.4.366

Duignan, M., Noble, J., Biddle, R., 2010. Abstraction and Activity in Computer-Mediated Music Production. Computer Music Journal 34, 22–33. https://doi.org/10.1162/COMJ_a_00023

- In this article, the authors analyse the framework of abstractions within computer-based music production – such as voice, temporal and process abstraction. These are the ways music is represented as it is created, for example one voice may utilise a ‘track’ on a Digital Audio Workstation. Through qualitative investigation and analysis based on activity theory, the authors uncover issues with historically-oriented UI design and suggest different approaches, for example, challenging the tape-style multitrack model with non-linear methods (and then further challenging this binary). The mediating role of the software music tool is discussed, and this is something I find useful when exploring this topic through a phenomenological lens. The abstraction framework provided could be useful for thinking about the design of new software.

Harper, A., 2017. How Internet music is frying your brain. Popular Music 36, 86–97. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261143016000696

Harper, A., Ebooks Corporation, 2011. Infinite music: imagining the next millennium of human music-making. Zero Books, Winchester, UK; Washington, USA.

Ihde, D., 2007. Listening and voice: phenomenologies of sound, 2nd ed. ed. State University of New York Press, Albany.

- This is a pioneering book into the phenomenology of sound - the first of its kind. In an age when vision leads, in the sciences as well as culture, Ihde attempts to change our way of thinking to one more balanced with the senses. Raw and honest, this book is laid out in such a way to ‘test the water’ with sound-oriented phenomenological discussion. Ihde often uses seemingly mundane, everyday examples, which are easy to understand. The chapters on voice and recording technology greatly helped with developing my own postphenomenological way of thinking.

Rosenberger, R., Verbeek, P. P. C. C., 2015. A field guide to postphenomenology. In R. Rosenberger, & P-P. Verbeek (Eds.), Postphenomenological Investigations: Essays on Human-Technology Relations (pp. 9-41). (Postphenomenology and the Philosophy of Technology). Lexington Books.

Selinger, Evan., 2006. Postphenomenology: A Critical Companion to Ihde. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Waugh, M., 2017. ‘My laptop is an extension of my memory and self’: Post-Internet identity, virtual intimacy and digital queering in online popular music. Popular Music 36, 233–251. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261143017000083

- This article studies the effect the Post-Internet age has on the production of music, and provides contemporary examples of Post-Internet musicians (Holly Herndon in particular is a big influence on me) and how they bring these themes into their work. Issues of identity in the Post-Internet age are unpacked, such as the idea of ‘digital queering’, common amongst Post-Internet musicians. This concept exists because of the multiple identities that are adopted when living in multiple networks simultaneously. My project was more concerned with the sound and production side, but I found the whole article useful in expanding my knowledge on Post-Internet thinking in general.

Weinberg, G., 2005. Interconnected Musical Networks: Toward a Theoretical Framework. Computer Music Journal 29, 23–39. https://doi.org/10.1162/0148926054094350

Young, M., 2010. Identity and Intimacy in Human-Computer Improvisation. Leonardo Music Journal 20, 97–97. https://doi.org/10.1162/LMJ_a_00022

Link to artefact: https://soundcloud.com/h_morley/sets/all-places-but

Many thanks to my friend Luke Phillips for his contributions on the audio artefacts (tracks 1b, 2b and 3b)