Bits

How is dataveillance creating new family narratives? What can metadata tell us, and what is left behind?

by Giulia Monterrosa

Parenting and Tracking Technology - Abstract

With the advance of ubiquitous computing, the use of tracking technology and personal surveillance technology has grown considerably over the last decade, asserting itself especially since 2008, after the foundation of the Quantified Self Movement, which promoted the collection and analysis of personal data.

Yet, tracking technology was not only imagined for the self, but in a broader sociocultural context, an extensive range of tools has been designed to allow users to track their loved ones (Fallon, K. and Koo, S., 2018). Particularly, several applications and sensors have been developed and marketed to help parents and family members monitor their children, generating and digitising information from pre-birth to adolescence. The integration of such technologies into the family context - practice which is often referred to as "caring dataveillance" - promotes the assessment of data of the youth towards the optimal development of healthy, self-sufficient individuals, whilst at the same time bestowing upon the parents a feeling of awareness of their control.

The type of surveillance that parents can execute thanks to tracking technology reaches out to a multitude of areas and activities (Marx, G. and Steeves, V.) : sensor-enabled 'smart diapers’ which facilitate the consistent monitoring of the infant’s health, or 'smart baby clothing' to feed sleep patterns algorithms; services that track online presence, scheduling the child's time online, blocking material, displaying searches; driving activity, by collecting not only GPS location but also the vehicle’s speed, acceleration, braking time, or giving the ability to lock-unlock its doors; and even drugs and alcohol consumptions, with the use of at home testing kits.

The sudden deployment of this technology and its establishment into two (or more) individuals’ relationship, can particularly reconstruct family dynamics. Deborah Lupton (2018), sociologist who has devoted most of her studies in understanding the impacts of self-tracking culture, reports that in a digitised control society, children are perceived as vulnerable and precious bodies. Equivalently, adults are expected to be responsible and fearful, hence tracking their children’s behaviour - online and offline - in the interests of protecting and prompting their health, development and wellbeing, is an essential factor of efficient and loving parenting.

However, a series of issues might arise when these objects get embedded into the youth. A study carried in 2019, shows that the invasiveness of monitoring a child can negatively affect trust and bonding, becoming counterproductive to the point of pushing the child further towards rebellion (Bench, 2019). Furthermore, it might be deleterious for children to know they are always able to turn to their parents when they are struggling, as it will offset the development of problem-solving skills and their stress-management capacity.

Particularly thought-provoking for this matter is the satirical and speculative text written by Gary Marx (2016), which takes this culture to an extreme.

"Children are expensive. According to some estimates a child born in 2010 will cost parents more than $250,000 before finishing college. Is your investment protected? Are you looking out for your kids by looking at them in the modern way? Do you know what your kids are hiding from you? Do you know who their friends are? Do you know who they talk to? Do you know where they go? Do you know where the convicted criminals in your neighbourhood live? Answers to such questions no longer need be based on surface appearances, the danger of dissimulation, or gossip. The precise discovery tools of modern science used by police, the military and titans of industry are now freely available to parents who care."

Bits

In the process of exploring the specifics in which caring dataveillance technology actively operates as an additional entity in the growth of two or more individuals’ relationship, I often found myself comparing my own childhood and the way I have been raised, to the words of parents and children who advocate the agency of such surveillance. What baffled me the most was the thought that an external agent - a piece of technology, an application, a sensor - could merge a natural process, a human act such as the growth of a child, into a computational cybernetic mechanism. And as I kept reading about the advantages and disadvantages of regularly monitoring the youth by making use of GPS signals, I then comprehended how different my narrative was from the one of today. And how different my narrative must have been in the eyes of the past generation, and the one before, and the one before again.

From this reflection, I initially decided to undertake this digital ethnographic study adopting a similar methodology to evocative autoethnography, originated by Arthur Bochner and Carolyn Ellis (2016), which aims to connect to the readers via the narration of personal lived experiences, identifying and positioning the self at the centre of cultural analysis.

I grew up in Rome, was raised by my father, immigrant from El Salvador, and by my sister, with whom I have an age gap of 9 years, a gap wide enough for me to perceive her presence as a motherly one too. Growing up without a mother meant being looked after by different people: grandparents, aunts, cousins, and many nannies. Digital technology was already becoming part of the ordinary, but its presence did not have an impactful role in my personal family dynamics. As I became a teenager, I did not own a mobile phone, and the only way for my dad to check if I got home after school when he was not there was by ringing our landline phone. Online systems to monitor school performance became available in our school just over the last year of high school. However, I also remember my father deciding not to access the system, as he thought I needed to be able to manage myself.

Nowadays we are able to create, collect and share fragmented memories as they were digital crumbs. We can take photographs and our phones will easily recognise who is in the picture and they will tell us when and where this was taken. Metadata is becoming the shadow of our narratives. In spite of this, data and the confusing systems which generate it can also often be inaccurate, and as technology tries to blend in the background, it truly leads to the construction of false, broken stories.

I decided to investigate this phenomenon with the help of my family using as a device old analog photographs from my childhood and tracing back to some of the fragments of my youth - as it was perceived by the adults around me - with the aim of creating a photo book in which images are replaced by text metadata.

I selected 46 photographs, and asked my father, my sister, and two of my aunts to take me through each one, recalling, if possible, the time and place of the picture, the situation that was occurring, and to just feel free to articulate whatever thoughts came to their mind. I recorded the conversations, noting down the length of each, as well as evaluating the level of uncertainty they disclosed when getting into details. Specifically, as I went back to the recordings, I tried to narrow the memories down to the following sets of information: date, occasion, place, GPS location - if applicable, other people recognised in the photo, person who took the photo, key points mentioned and discussed.

This process of holding open conversations with my relatives, wanting to organise them in data points, was not only quite emotional, but most importantly it helped me to highlight even more the limits in which data can attain, emphasising the overwhelming presence of human sentiments that can often define the interpretation of the data itself.

An aspect that truly moved me as I was going through the photos of the early phase of my life (up to 3 years of age), was noticing that my dad would categorise time as in "prima di mamma"(before mum) and "dopo mamma" (after mum) - meaning before the death of my mother, and after. It was incredible to see how perception of time can change from person to person purely on the base of one factor that has truly marked their life. Therefore, I felt that trying to deduct the precise date of a photograph suddenly became futile in comparison to the words of my dad.

Diversely, my sister had her own distinct method to help her place a memory in time. She would look at her clothes, the length of her hair or her spectacles’ frame. She would maybe struggle to remember the precise moment a photo was taken, but would focus on the objects in the background to extract another variety of information.

Several questions emerged. Is the act of not being able to remember a moment or a face a symbol of disregard and inattention ? Does having a longer conversation with someone have more value than one that only lasted a few minutes ? What gets lost in quantification? How could data ever take in account the messy, visceral, complex components of human behaviours?

And with all these questions in mind, I have then realised how the data itself was not as relevant as I thought, but what was truly important was the metadata of each conversation, which by some means could authenticate the connection and the value bestowed to these memories, unique to every family member. I then averaged the information given by each, trying to pull out the data that seemed to be more reliable. Ultimately, once a photograph looked nothing more than just a list of names and numbers, I perceived the lack of attachment I had with it. Such lexicon would, perhaps, be truly acknowledged only by a computational system, similarly to the way tracking devices make sense of users’ data.

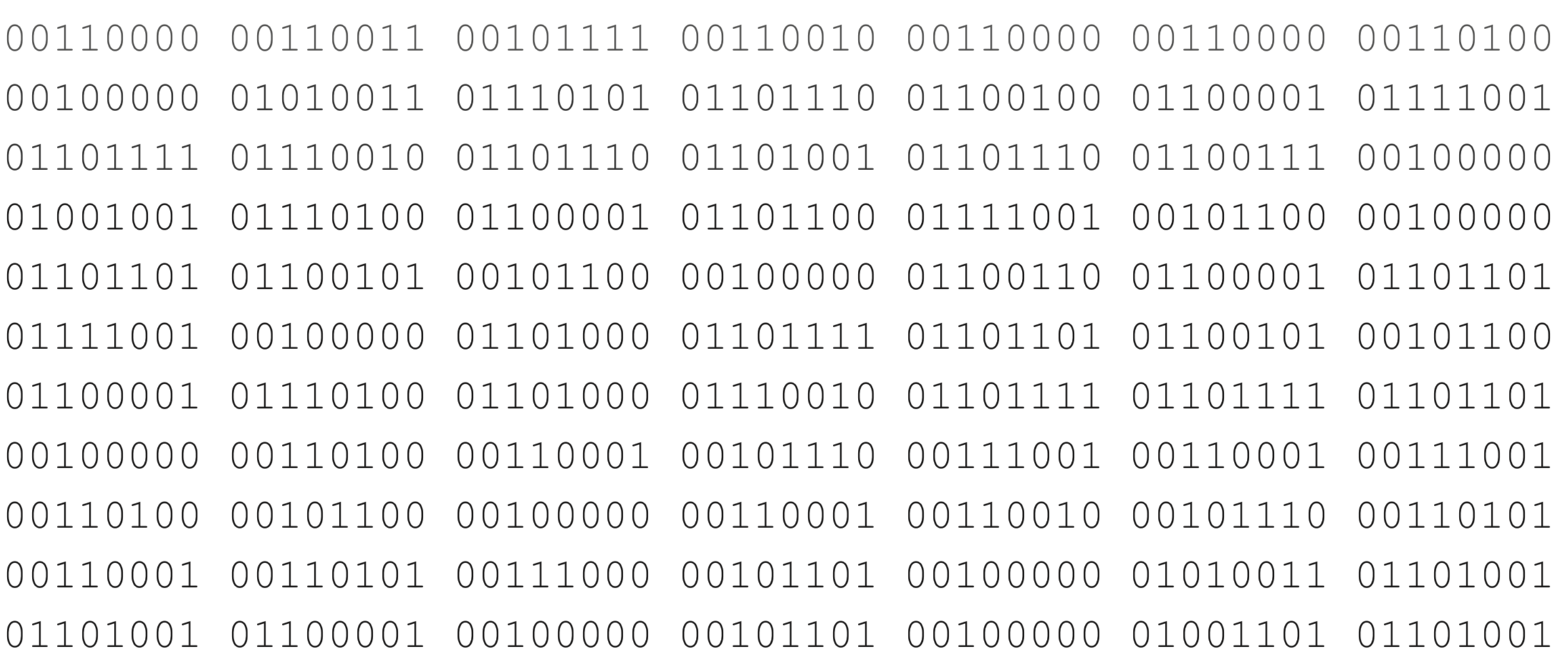

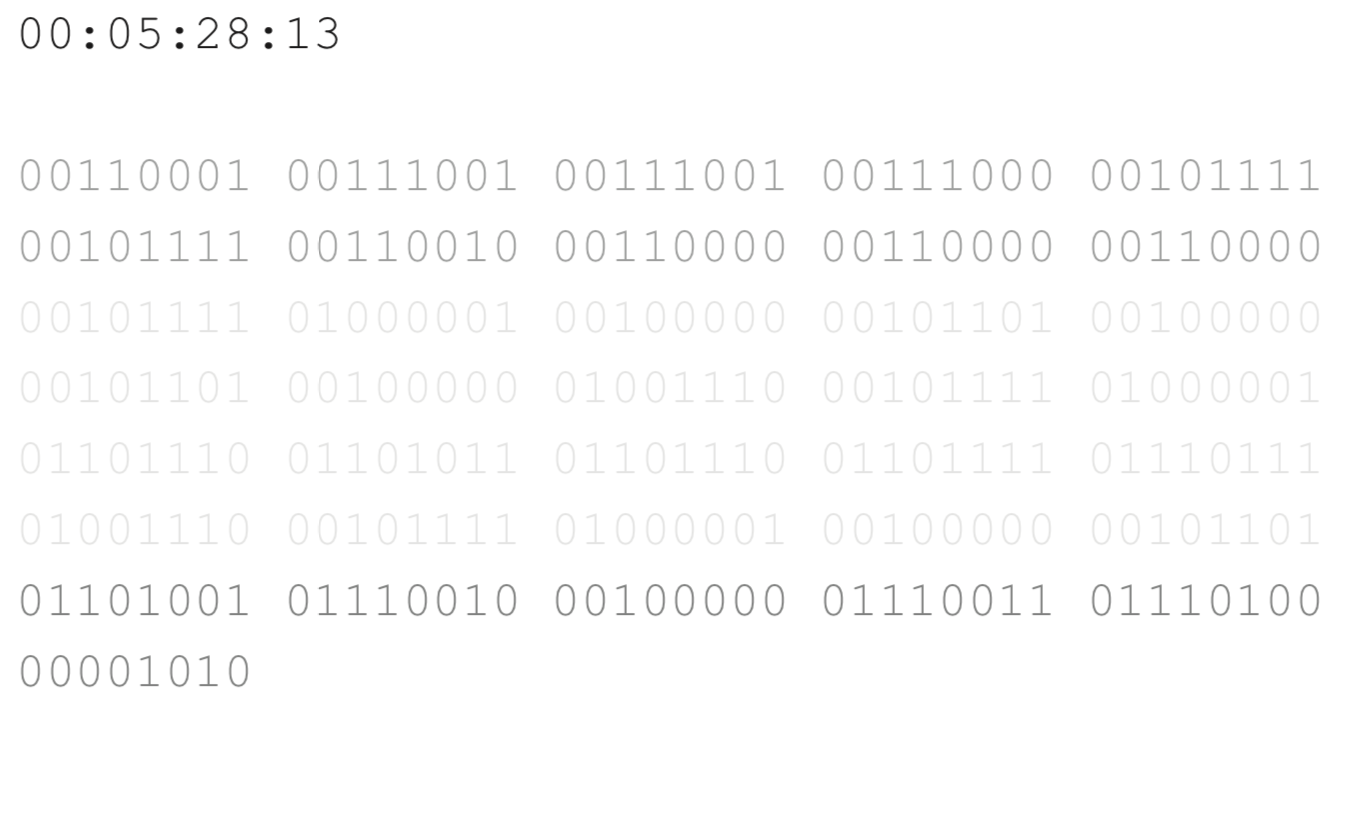

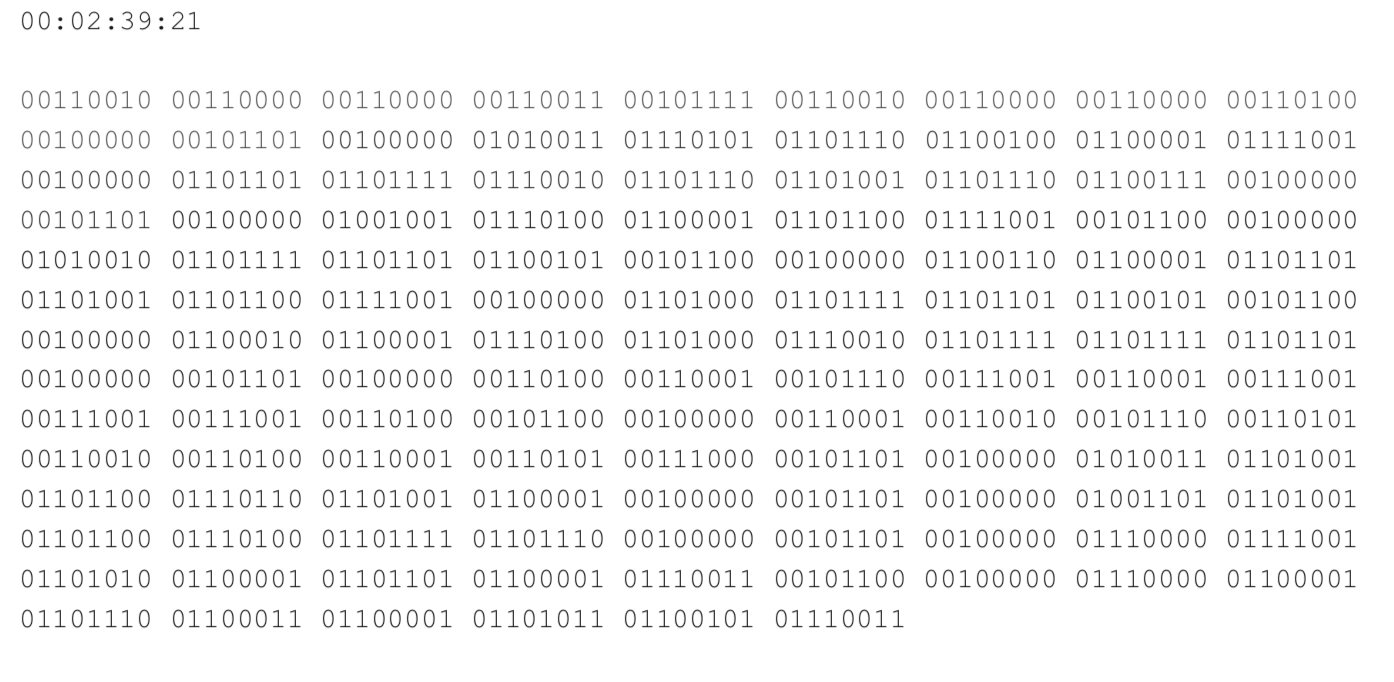

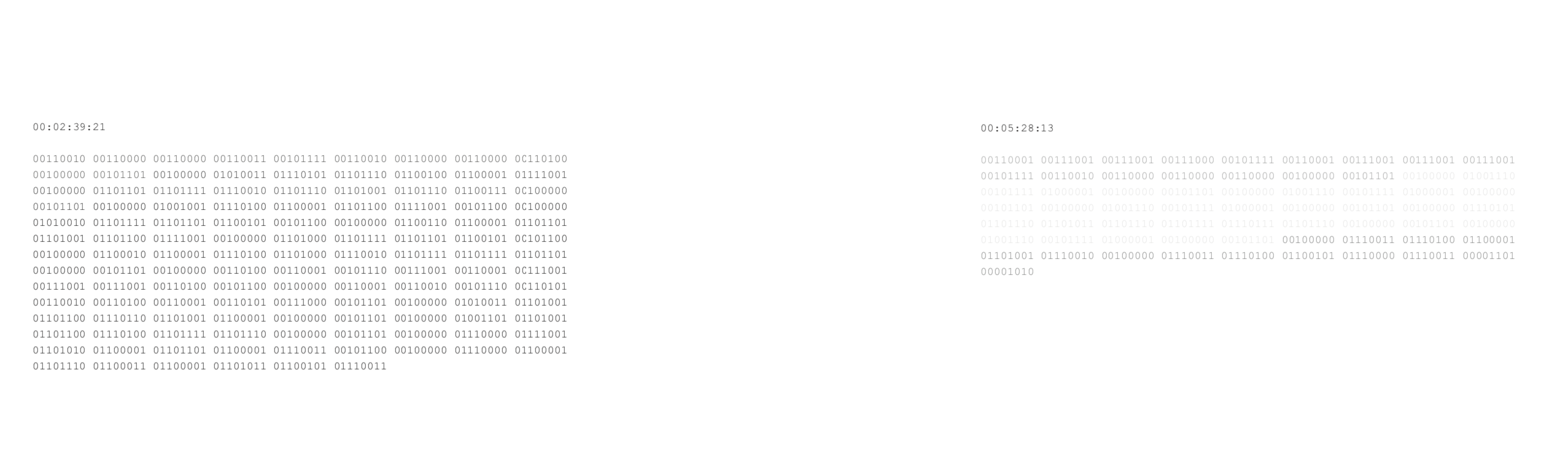

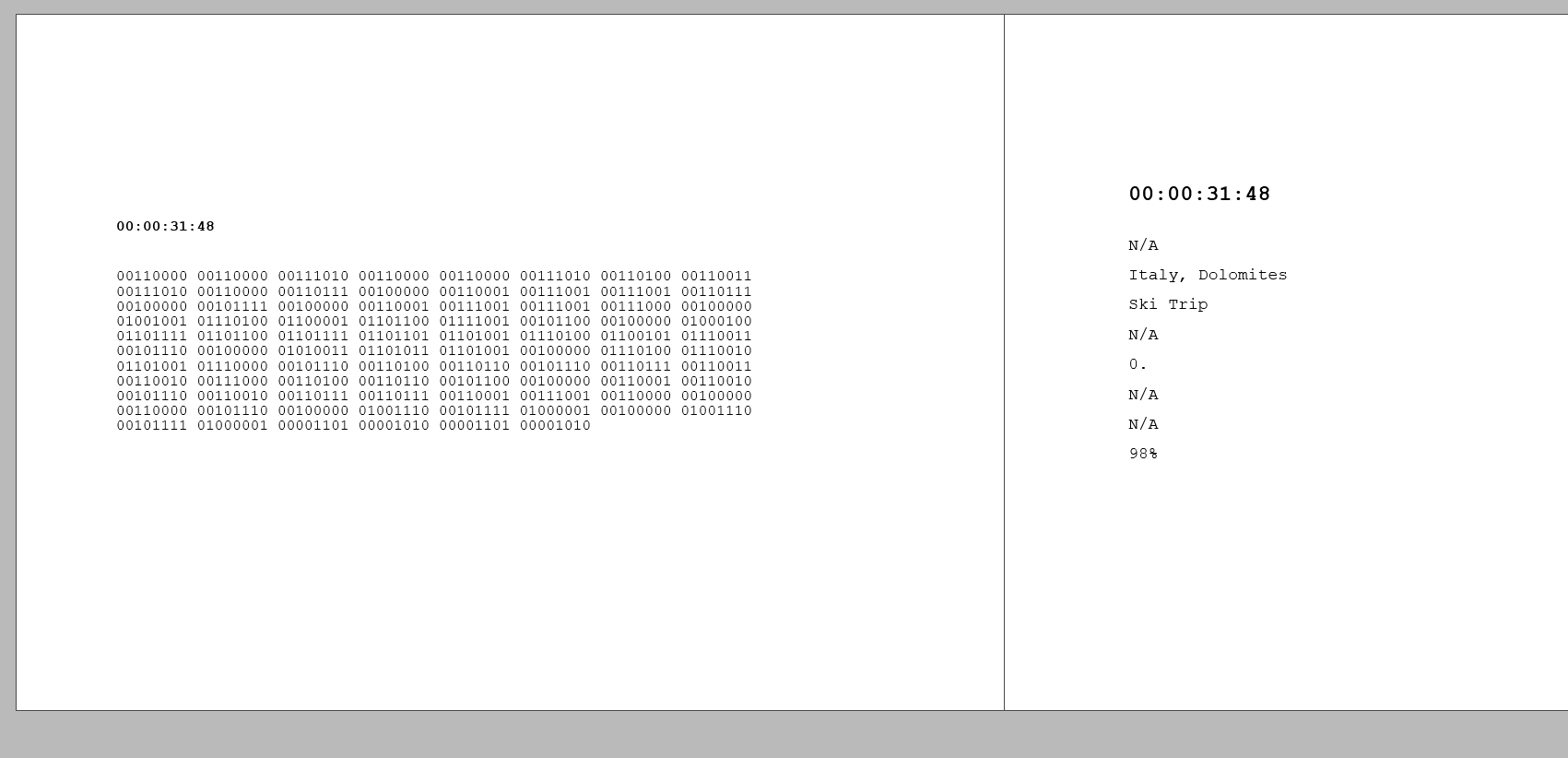

In light of this, I have then decided to design and display the data collected by converting it into binary ( or bits ), the basic language that characterises the way computers communicate, a series of 1s and 0s that are electrical signals which register the two states of being on or off.

Nonetheless, I have also decided to preserve two elements of the metadata. The average time of conversation that was spent to describe each photo, and the reliability of the data that was extracted. The latter was manually assigned by me to each piece of information in the form of a percent value of uncertainty that the person had presented; I then used said value as color opacity value of the text, hence the lighter the text is, the less reliable the data is.

This process of holding open conversations with my relatives, wanting to organise them in data points, was not only quite emotional, but most importantly it helped me to highlight even more the limits in which data can attain, emphasising the overwhelming presence of human sentiments that can often define the interpretation of the data itself.

An aspect that truly moved me as I was going through the photos of the early phase of my life (up to 3 years of age), was noticing that my dad would categorise time as in "prima di mamma"(before mum) and "dopo mamma" (after mum) - meaning before the death of my mother, and after. It was incredible to see how perception of time can change from person to person purely on the base of one factor that has truly marked their life. Therefore, I felt that trying to deduct the precise date of a photograph suddenly became futile in comparison to the words of my dad.

Diversely, my sister had her own distinct method to help her place a memory in time. She would look at her clothes, the length of her hair or her spectacles’ frame. She would maybe struggle to remember the precise moment a photo was taken, but would focus on the objects in the background to extract another variety of information.

Several questions emerged. Is the act of not being able to remember a moment or a face a symbol of disregard and inattention ? Does having a longer conversation with someone have more value than one that only lasted a few minutes ? What gets lost in quantification? How could data ever take in account the messy, visceral, complex components of human behaviours?

And with all these questions in mind, I have then realised how the data itself was not as relevant as I thought, but what was truly important was the metadata of each conversation, which by some means could authenticate the connection and the value bestowed to these memories, unique to every family member. I then averaged the information given by each, trying to pull out the data that seemed to be more reliable. Ultimately, once a photograph looked nothing more than just a list of names and numbers, I perceived the lack of attachment I had with it. Such lexicon would, perhaps, be truly acknowledged only by a computational system, similarly to the way tracking devices make sense of users’ data.

In light of this, I have then decided to design and display the data collected by converting it into binary ( or bits ), the basic language that characterises the way computers communicate, a series of 1s and 0s that are electrical signals which register the two states of being on or off.

Nonetheless, I have also decided to preserve two elements of the metadata. The average time of conversation that was spent to describe each photo, and the reliability of the data that was extracted. The latter was manually assigned by me to each piece of information in the form of a percent value of uncertainty that the person had presented; I then used said value as color opacity value of the text, hence the lighter the text is, the less reliable the data is.

Final Notes:

A PDF of the book is available here.

Given the circumstances in which this artefact has been produced, there are a few elements that have or might have been somewhat affected. Foremost, all the conversations have been hold remotely via video call, which surely has created a different and less intimate surrounding. Additionally, I would have liked to make use of other methods to gather metadata, such as sentiment analysis or emotion recognition. Finally, I would have also liked to print a physical copy of the photo book.

Annotated Bibliography

1. Bochner, A. and Ellis, C. (2016) Evocative Autoethnography: Writing Lives and Telling Stories. Routledge

Written as the story of a fictional workshop, in this comprehensive text the authors introduce the concept of evocative autoethnography as a methodology, describing how to examine ethical issues, dilemmas and responsabilities. The authors use their own personal stories and experiences to help guide the workshop.

2. Calle, S. (2015) Suite Venitienne

Sophie Calle was a very significant reference in the development of my artefact. The artist makes portraits of herself and strangers, trailing and tracking movements through illustrations and black and white photographs.

3. Lupton, D. (2018) 'Caring Dataveillance: Women’s Use of Apps to Monitor Pregnancy and Children’ Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/326647795_Caring_Dataveillance_Women's_Use_of_Apps_to_Monitor_Pregnancy_and_Children (Accessed: 22nd March 2020)

Deborah Lupton is an Austrian sociologist who has been studying the effects of self-tracking culture. In this paper, she analyses a variety of apps available for monitoring pregnancy and health, considering their implications. Here, Lupton brought together two major literatures, which are dataveillance and feminist new materialism.

Bibliography

Agre, P. (1994) ‘Surveillance and capture: two models of privacy’. The Information Society. 10, pp. 101-127.

Belkhyr, Y. (2019) The terrifying now of big data and surveillance: A conversation with Jennifer Granick. Available at: https://blog.ted.com/the-terrifying-now-of-big-data-and-surveillance-a-conversation-with-jennifer-granick/.(Accessed: 2nd April 2020)

Bench, R. (2019) A literature review evaluating parental tendencies in prior adolescent substance users. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0190740918308569. (Accessed: 20th March 2020)

Collie, M. (2019) Parents are using tech to ‘track’ their kid’s location. Does it cross the line? Available at: https://globalnews.ca/news/6187813/tracking-kids-gps/. (Accessed: 20th March 2020)

Dickson, E. (2020) 3 Apps for Consensual Partners to Share TMI. Available at: https://www.dailydot.com/debug/love-surveillance-spying-apps/. (Accessed: 22nd March 2020)

Dow Schüll, N. (2016) ‘Data for life: Wearable technology and the design of self-care’. BioSocieties 11(3)

Essén, A. (2008). 'The two facets of electronic care surveillance: An exploration of the views of older people who live with monitoring devices.' Social Science & Medicine, 67(1), 128-136.

Fallon, K. and Koo, S. (2018) Explorations of Wearable Technology for TrackingSelf and Others. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/324066650_Explorations_of_wearable_technology_for_tracking_self_and_others. (Accessed: 22nd March 2020)

Haraway, D. J.; Gane, N. (2006) 'When We Have Never Been Human, What Is to Be Done? Interview with Donna Haraway.' In: Theory, Culture & Society. 23(7–8): 135–158.

Hayles, N. K. (2005) My Mother Was a Computer. Digital Subjects and Literary Texts. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Herder, J. (2018) 'Information as Truth: Cybernetics and the Birth of the Informed Subject’. Behemoth A Journal on Civilisation. Available at: https://freidok.uni-freiburg.de/fedora/objects/freidok:16943/datastreams/FILE1/content. (Accessed: 29th March 2020)

Leaver, T. (2017). 'Intimate surveillance: normalizing parental monitoring and mediation of infants online'. Social Media + Society,3(2).

Lupton, D. (2014) Self-tracking Cultures: Towards a Sociology of Personal Informatics. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/290766116_Self-tracking_cultures_Towards_a_sociology_of_personal_informatics (Accessed: 25th March 2020)

Lupton, D. (2016a) 'Digital Companion Species and Eating Data: Implications for Theorising Digital Data-Human Assemblages'. Big Data & Society January - June: 1–5.

Lupton, D. (2018) 'Caring Dataveillance: Women’s Use of Apps to Monitor Pregnancy and Children'. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/326647795_Caring_Dataveillance_Women's_Use_of_Apps_to_Monitor_Pregnancy_and_Children . (Accessed: 22nd March 2020)

Lupton, D. & Williamson, B. (2017). 'The datafied child: The dataveillance of children and implications for their rights.' New Media & Society. Available at: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1461444816686328

Marx, G. (2016). Windows into the Soul: Surveillance and Society in an Age of High Technology. University of Chicago Press

Marx, G. and Steeves, V. (2010) From the Beginning: Children as Subjects and Agents of Surveillance. Surveillance & Society 7(3/4). Available at: https://web.mit.edu/gtmarx/www/childrenandsurveillance.html . (Accessed: 25th March 2020)

Moore, P. (2018) The Quantified Self in Precarity: Work, Technology and What Counts. London: Routledge.

Nafus, D., Thomas, S. and Sherman, S. (2018) ‘Algorithms as Fetish: Faith and Possibility in Algorithmic Work’ Big Data & Society.

Neuringer, A. (1981) ‘Self-Experimentation: A Call for Change’. Behaviorism, 9 (1):79-94

Pangaro, P. (2021) ’Foundational Principles of Cybernetics'. Available at: https://vimeo.com/41782295 . (Accessed: 20th March 2020)

Reynolds, J. (2019) Why Parents Should Think Twice About Tracking Apps for their Kids . Available at: https://theconversation.com/why-parents-should-think-twice-about-tracking-apps-for-their-kids-114350 . (Accessed: 20th March 2020)

Russo, E. (2015) Sophie Calle’s Suite Venitienne: Following as Performance and Book. Available at: https://artcritical.com/2015/07/16/emmalea-russo-on-sophie-calle/ . (Accessed: 3rd April 2020)

Sjoklint, M. (2015) The Measurable Me: the Influence of Self-Tracking on the User Experience. Available at: https://openarchive.cbs.dk/bitstream/handle/10398/9222/Mimmi_Sjöklint.pdf?sequence=1 . (Accessed: 3rd April 2020)

Skinner, B.F. (1938) The behavior of organisms: An experimental analysis. New York, NY: Appleton- Century.

Taylor, A. (2017) Metadata: Writing on the Back of a Digital Photo . Available at: https://www.picturesandstories.com/news/2017/2/13/metadata-writing-on-the-back-of-a-digital-photo . (Accessed: 10th April 2020)

Williamson, B. (2014)'Calculating Children Through Technologies of the Quantified Self' . Available at: https://www.academia.edu/7169396/Calculating_children_through_technologies_of_the_quantified_self . (Accessed: 20th March 2020)

Whitson, J. (2013) Gaming the Quantified Self. Available at: https://ojs.library.queensu.ca/index.php/surveillance-and-society/article/view/gaming . (Accessed: 29th March 2020)

Wolf, G. (2011) What is The Quantified Self? Quantified Self . Available at: http://quantifiedself.com/2011/09/our-three-prime-questions/. (Accessed: 29th March 2020)

Artists and Relevant Projects

Acconci, V. (1969) Following Piece .Photos/text works. Available at: http://www.vitoacconci.org/portfolio_page/following-piece-1969/ . (Accessed: 3rd April 2020)

Dovey, M. (2015) How to be more or less human. Available at: https://maxdovey.hashbase.io/howtobemoreorless/ . (Accessed: 2nd April 2020)

Dovey, M. (2017) Respiratory Mining . Available at: https://maxdovey.hashbase.io/Respiratory_Mining/ . (Accessed: 2nd April 2020)

Frick, L. (2019) Felt Personality . Available at: https://www.lauriefrick.com/works . (Accessed: 28th March 2020)

Lupi, G. and Posavec, S.(2015) Dear Data. Available at: http://www.dear-data.com/theproject . (Accessed: 2nd April 2020)

Nicenboim, I. (2015) Objects of Research . Available at: https://iohanna.com/Objects-of-Research . (Accessed: 2nd April 2020)

Odea, T. (2016) Totem . Available at: http://iamtomodea.com . (Accessed: 2nd April 2020)

Odea, T. (2017) Self- Portrait SNP. Available at: http://iamtomodea.com. (Accessed: 2nd April 2020)

Superflux (2015) Uninvited Guests . Available at: https://superflux.in/index.php/work/uninvited-guests/# (Accessed: 8th April 2020)

Superflux (2019) Better Care. Available at: https://superflux.in/index.php/work/better-care/# (Accessed: 8th April 2020)

Tan, L. (2015) Reality Mediators. Available at: http://lingql.com/reality-mediators/ . (Accessed: 2nd April 2020)

Tega Brain (2015) Unfit Bits.Available at: http://www.tegabrain.com/Unfit-Bits. (Accessed: 2nd April 2020)

Thornton, P. (2017) What is Orwell’s 1984 really worth?. Available at: https://pipthornton.com/2017/08/28/what-is-orwells-1984-really-worth/. (Accessed: 2nd April 2020)