An Examination of the Application of Computation in Fine Art Practices

Laura Traver

A frequent and fundamental distinction has been made historically between fine art and computational art. Variously, computational art has been considered to be an “explosive charge” to the art world (1); or, over before it has begun (2). At times, computational art has been excluded by the art world as “a newcomer still, an intruder and an alien” (3) and left to exist in a “computer art ghetto” (4). At other times, it is the art establishment which is being rejected (5), or, perhaps, which is no longer relevant, having conceptually refined itself into a state of isolated confusion and non-existence in the 20th century (6).

The creative innovations of computation have seemed irreverent, even threatening, to fine art on occasion: a computer-made Mondrian can be better than the real thing (7); a “perfect” painting can now be produced using a formula and viewer gaze-tracking technology (8); and drawing robots and the pursuit of creativity by artificial intelligence researchers are seemingly taking the paintbrush right out of artists’ hands (9). It is understandable that, in the shadow of “the electronic superhighway” (10), an artist could feel “shame… when facing painting in all its valuable antiquatedness” (11). However, in contrast to traditional artistic tools, which have retained their form and function for hundreds of years, computational technology has been developed and changed dramatically in a short space of time (12). It is natural, therefore, that computational practices might only be slowly absorbed into fine art practices and that, as the face of computation becomes less technical, and less reliant on algorithmic knowledge (13), computational processes and technology will be adopted with increasing frequency by fine artists. This study will explore where and how fine art practice is adopting aspects of computation and consider the future directions for fine art practice through a series of three studies produced in response to this research. For the purposes of this research, computation is used in the broadest sense and will include computational technology, such as 3D printing, the pixelated image, and computer programmes. Selected works will be by artists with fine art training and whose practices have a dialogue with the traditional media of painting, drawing, or sculpture. Aspects of Rosalind Krauss' view on the post-medium will be considered throughout.

Comparatively frequent use of computational technology as a tool, woven into creative process, is made by fine artists exploring the tangible, specific, and, what Krauss termed, the “Greenbergized” (14) media of painting and drawing. Albert Oehlen's computer-aided works, such as Deathoknocko (2001, pictured), layer oil paint with an inkjet printed canvas in “a rendering of the visual cacophony of daily life in the information age” (15). Similarly, Laura Owen’s scanned newspaper clippings are interwoven with gestural painting (16), and Wade Guyton uses computers, printers, and iPhones in his practice to create paintings and drawings (17). The recent work of portraitist Jonathan Yeo, however, presents the possibilities of a symbiotic interaction between fine artist and computation and for hybrid works to embody the “digital/virtual and material/embodied realities at the same time” and break free from from the limitations of the modernist medium (18).

Yeo’s work was featured in the recent From Life exhibition at Royal Academy in London for his use of virtual reality, 3D printing, and traditional bronze casting methods to create art. The artist worked closely with Google Arts and Culture and used Tilt Brush software to paint in a three-dimensional virtual space, and then worked with OTOY’s LightStage scanner to create a 3D scan of his face, which was subsequently reworked in Tilt Brush, 3D printed, and finally cast in bronze using traditional methods by the famous foundry, Pangolin Editions. The artist worked experimentally between new technology and traditional technology to create “solid structures based precisely on the kind of gestural marks which painters would normally use on a canvas” resulting in what the artist termed “a hybrid of painting and sculpture” (19).

From Joseph Kosuth’s perspective, art such as Yeo’s could be regarded as the outcome of the work of the “militantly reductive modernism” of the 20th century, which “turned painting inside out and had emptied it into the generic category of Art” (20), creating space for hybrid, or generic, art such as Yeo’s to develop. Indeed, the additional fact that Yeo is an acclaimed portrait artist with no background in sculpture who considers this technology will allow “artists from a range of disciplines to have a go too” indicates the potential for computational technology in a post-medium context to break boundaries even within the fine arts (21), to “democratise the arts” (22), and to create something new “in the face of a medium now cut free from the guarantees of artistic tradition” (23).

Computational technology, however, also raises uncomfortable questions for fine artists as much as it offers hope for the future. The discomfort was evident in the large group show Brand Innovations for Ubiquitous Authorship exhibition at Higher Pictures in New York in 2012. According to Michael Connor the process of creation was within the “truncated forms of customisation available on the internet” (24). Artists each submitted an object produced using commercial custom printing and fabrication services (25). Each object was delivered directly to the gallery without being seen by the artist beforehand and the unboxing of each artwork was recorded for YouTube with funerary titles including the artist’s name, such as “Unboxing Jon Rafman” (26).

According to the press release for the exhibition, the result of the use of commercial services to produce the art “will be a gallery of art, artefact and artifice”(27). The idea that digital, commercial fabrication is creatively restrictive and that the resulting art is “artifice” is indicative of the discomfort that using computational technology can raise in artists. This discomfort is not new, or only about computational technology, however. Artistic skill in relation to mechanical and technical skills has been a source of debate for over a century (28), and raises the interrelated questions of authenticity and authorship (29). While the Duchampian readymade and Conceptualist systems on the one hand allowed for “authorship at a distance” (30), they also created confusion about what “constitutes skill in art after the readymade” (31). Moreover, the reproducibility that is frequently associated with the use of technology for artistic purposes challenges the traditional idea of the original piece of artwork and the importance of the artist, both of which are conventionally considered to be missing in a reproduction.

Computation in a post-medium context has the potential to update this 20th century discomfort around skill, originality, and authenticity and create “new ways to perceive art” (32). In Howlin Lupus (2015), Sarah Szczesny fractures the surface of a painting into a “network of individuated painterly attributes” (33) by panning a camera across white brushstrokes on ground and the grainy shapes of a photocopy of a drawing. In so doing, the artist turns the art not just into one image, but into many images, or even paint-pixels, or parts of painterly programming code. In her work, the image is not conceptually divided between the original and the reproduced image, or between “here thing-there image. Here I - there it. Here subject - there objects. The senses here - dumb matter over there” (34). There is no original, authentic, physical piece of art that is elsewhere and only represented by the inauthentic reproduction, because there is no specific medium in the Greenberg sense (35), but, instead, a hybrid medium chosen by the artist for their specific purpose.

The digital image as reproduction is subject to many interpretations which frequently tie the intangible digital image to a missing, original, probably tangible, artwork presumably of modernist media. The idea of the dematerialised, disembodied image and “consumable picture easily transmissible in time and space” (36) over the internet is common. It is undeniable that images of art “can travel as far and fast as an audience commands “ and they can be “lost amidst the digital debris” online (37), disappear as “ephemeral” data (38), or simply fall out of memory online due to the “aggressively amnesiac urge” (39) of the internet. Ei Arakawa and Shimon Minamikawa, for example, explore the speed and changing situations in which a painting may be seen online in Paris Adapted Homeland Episode 6 (2013) where Arakawa is shown balancing paintings by Minamikawa in front of his face while running on a treadmill in front of a changing green screen (40). In a post-medium context, however, images do not have to be the inadequate clone of the lost, original, art object, they can have a substance of their own. Laura Marks considers the image to have substance by being “existentially linked to the physical states of subatomic particles” (41) and Hito Steyerl considers images to be material objects which can be “violated, ripped apart, subjected to interrogation and probing. They are stolen, cropped, edited and reappropriated. They are bought, sold, leased. Manipulated and adulated. Reviled and revered. To participate in the image means to take part in all of this” (42). Josh Smith explores the proliferation and duplication of art-images in his work by pressing together still-wet canvases so that two paintings leave an imprint on each other and, in so doing, duplicates images which parrot each other (43).

The image does not have to be considered as physical material to be used by fine artists, however. Fine art, cut free from the specific medium (44), can uniquely move between the material and non-material as selected by the individual artist. Celia Hempton, for example, paints users online live whilst having a conversation using the video chat function of social networking platform chatrandom.com in her series Chat Random (45). Both Erika Balsom and Omar Kholeif comment on the fact that painterly attributes, such as gesture, style, and brush strokes, are denied to the viewer (46), and that “(t)hick brushstrokes retreat from photographic detail” (47). This reflects a more traditional approach to the interpretation of a pixelated image as separated from the 'real' Greenbergian art object. Brush strokes and painterly attributes can, alternatively, be regarded as having been brought to the forefront by making painting accessible, even casual (48), through online video chatting. The artist is not a victim of the speed of images moving away from her, or the loss of authenticity through the pixels of a screen, but is working in hybrid media selected by the artist herself and working between the material and non-material to produce separable, tangible paintings and non-physical art at the same time.

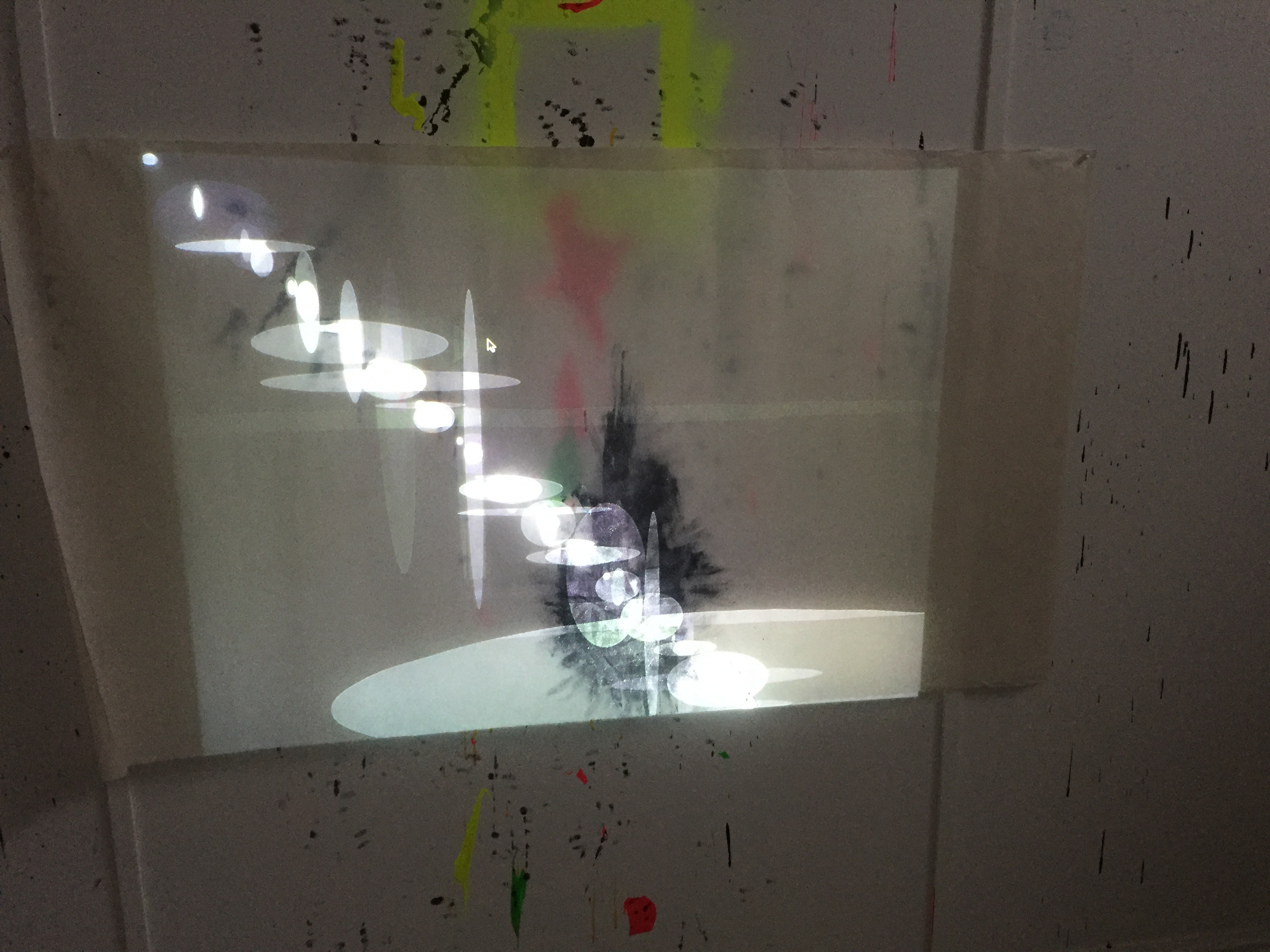

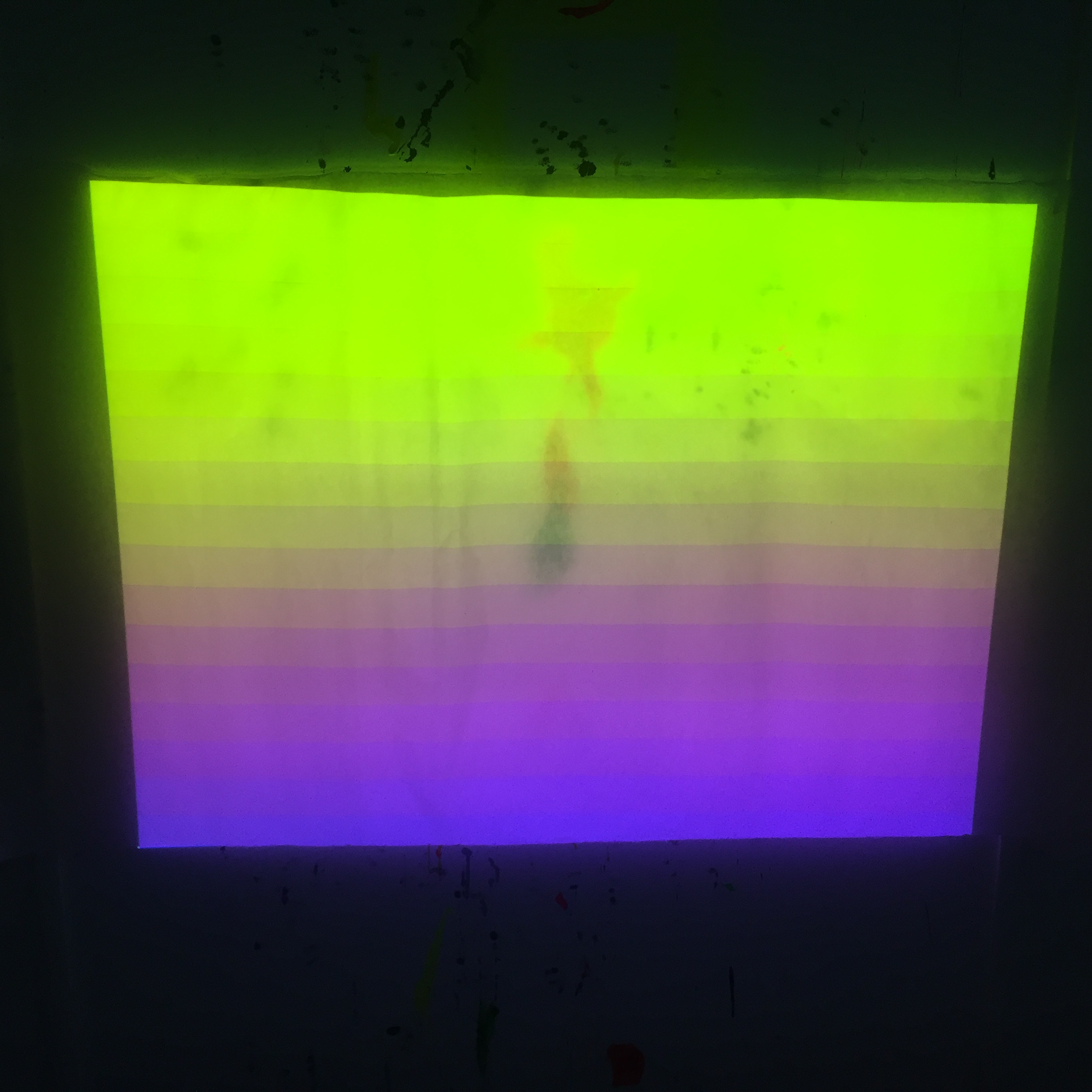

As a result of this research into the application of computation in fine art practices, I produced three studies of my own by projecting Processing sketches on to paper and interacting with them. The reality of John Jr Simon’s statement that the loop is the strength and distinguishing characteristic of computers compared to the physical world was rapidly apparent from the first sketch - the real-time movement of sketches projected on to paper, and my static marks capturing my response were starkly different. It also highlighted the truth of the words of Lewis F Day in 1885 that the “fault of the man is in trying to compete with the machine, just as the machine is misapplied in the attempt to compete with him” (49). For the second and third sketches, I experimented with letting the computer do what it did rather than trying to keep up with it. The next step would be for the computation to interact with me and intertwine the processes further into symbiosis. It would also be interesting to combine the work of dancers and choreographers, such as Yacov Sharir, “to manipulate, extend, distort, and deform information as well as experience of the body” (50) with gestural painting.

The possibilities for the future of fine art and computation free from the specific 20th century media of painting, drawing, and sculpture, and the cyclical and reductive debates around authenticity, authorship, and the idea of the original piece of art, is limitless. There are many non-traditional artists making imaginative work which is accessible to fine artists. Tom White’s Digital Finger Painting (1997) wired up a medical bladder filled with soy sauce to give an approximation of touching paint while on a computer (51). In the series Palm Paintings, Red Burns embedded a palm computer in each of the paintings “to create a mirroring of virtual and physical abstractions, where one abstraction informs the other” and, so, worked interactively and physically with computing to probe painting (52). In 2012, Michael Quantrill set up a whiteboard with a laser matrix and connected this to a computer so that the “creative process is fused with machine interpretation. The final piece is thus an inseparable intertwining of human and machine processes” (53). Fine art and computation have many possibilities together - indeed, Casey Reas considers computation to be inherently creative, and believes that visual artists and designers have the opportunity to write their own languages and “to define computation in a hybrid of visual and text structures” (54) and create new models and creative software (55). In addition, the expressive and artistic possibilities that developments in commercially available technology will provide for artists in the future, such as virtual technologies like Tilt Brush, are wide-ranging.

Computation provides a “limitless palette” (56) for fine artists. Alan Kay called computers the first “metamedium” whose content is “a wide range of already-existing and not-yet-invented media” (57) and, in the “face of Medium now cut free from the guarantees of artistic tradition” (58), there is no medium and any medium for artists to use. Moreover, computing and creating fine art are not very different: “software is a living record of a thought one has had, or is having, about how the world ought to be” (59), and there is little difference between this and the mind and works of many fine artists.

Endnotes

1. Hans-Peter Schwarz, a founding director of Zentrum fur Kunst und Medien-technologie in Germany described media art as an “explovie charge” in Usselmann, Rainer, “The Dilemma of Media Art: Cybernetic Serendipity at the ICA London”, Leonardo, Vol. 36, No. 5, (2003), pp. 389-396, at p. 389.

2. Manovich, Lev, "The Death of Computer Art", accessed 20 March 2018, http://rhizome.org/community/41703/

3. Huhtamo, Erkki, “Time Traveling in the Gallery: An Archeological Approach in Media Art”, Moser, Mary Anne, and MacLeod, Douglas, Immersed in Technology: Art and Visual Environments, (The MIT Press, 1996), pp. 233-268 at p. 256.

4. The artist Rebecca Allen in Taylor, Grant D., When the Machine Made Art: The Troubled History of Computer Art, (Bloomsbury Academic, 2014), p. 179.

5. Graham Harwood of Mongrel was asked to make a piece for the Tate site in 2000 and produced a subversive interviension, Tate, “About the Harwood De Mongrel Tate Site”, accessed 15 March 2018, http://www2.tate.org.uk/netart/mongrel/home/siteguide.htm

6. Krauss, Rosalind, A Voyage on the North Sea: Art in the Age of the Post-Medium Condition, (Thames and Hudson, 2000), p. 6.

7. An experiment carried out by Michael Noll at Bell Telephone Laboraties in which a sample audience attempted to distinguish a genuine Mondrian painting from a computer-generated fake - 59% of the people who were shown both the Mondrian and the computer version preferred the latter, 28% identified the computer picture correctly, and 72% thought that the Mondrian was done by computer in Usselmann, “The Dilemma of Media Art: Cybernetic Serendipity at the ICA London”, p. 390.

8. Jonas Lund in View Improvised Painting made a self optimising digital painting which stored the gaze of viewers iteratively to create the "perfect" painting in Lund, Jonas in conversation with McCormack, Seamus, “Programming Subjectivity”, Kholeif, Omar, ed., Electronic Superhighway: From Experiments in Art and Technology to Art After the internet, (Whitechapel Gallery, 2016), pp. 232-239 at p. 234.

9. Barry, Judith in conversation with Perks, Sarah, “The Dynamics of Desire”, Kholeif, Electronic Superhighway, pp. 226-231 at p. 231.

10. Nam June Paik in Blazwick, Iwona, “Electronic Superhighway”, Kholeif, Electronic Superhighway, pp. 20-23 at p. 20.

11. Stakemeier, Kerstin, “Controlled Medium Specificity: Networks and Painting”, Ammer, Manuela, Hochdorfer, Achim, and Joselit, David, eds., Painting 2.0: Expression in the Information Age: Gesture and Spectacle, Eccentric Figuration, Social Networks, (Prestel, 2015), pp. 262-267 at p. 265.

12. Stakemeier, “Controlled Medium Specificity: Networks and Painting”, Ammer, Hochdorfer, Joselit, eds., Painting 2.0: Expression in the Information Age, p. 265.

13. Taylor, Grant D., When the Machine Made Art: The Troubled History of Computer Art, (Bloomsbury Academic, 2014), p. 50.

14. Krauss, A Voyage on the North Sea, p. 6.

15. Kholeif, Omar, “Electronic Superhighway: Towards a Possible Future for Art and the Internet”, Kholeif, Omar, ed., Electronic Superhighway: From Experiments in Art and Technology to Art After the internet, (Whitechapel Gallery, 2016), pp. 24-33 at p. 31.

16. Hochdorfer, Achim, “How the World Came in”, Ammer, Manuela, Hochdorfer, Achim, and Joselit, David, eds., Painting 2.0: Expression in the Information Age, pp. 15-27 at p. 25.

17. Whitney Mueum of American art, accessed 25 Marc 2018, https://whitney.org/Exhibitions/WadeGuyton

18. Edward Zajec believed that the “far-reaching consequence” of computer art was not in the art objects themselves, but in the process by which they were made in Taylor, When the Machine Made Art, p. 136. The new aesthetic would “no longer be on form and contemplation, but rather on formation and interaction of man and machine” in Hope, Cat and Ryan, John, Digital Arts: An Introduction to New Media, (Bloomsbury Academic, 2014).

19. "A New Way of Making Sculpture", accessed 18 March 2018, https://www.jonathanyeo.com/from-virtual-to-reality

20. Krauss, A Voyage on the North Sea, p. 10.

21. Luke, Ben, “From pencil and paper to virtual reality: working from life today”, accessed 18 March 2018, https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/article/magazine-from-life-ben-luke

22. Lev Manovich wrote that with digital arts there is a breakdown of divisions between art forms in Hope, and Ryan, Digital Arts, p 13 and 25.

23. Krauss, A Voyage on the North Sea, p. 6.

24. Connor, Michael, “Post-Internet: What It Is and What It Was”, Kholeif, Omar, You are Here: Art After the Internet, (Cornerhouse, 2014), pp. 56-64 at p. 61.

25. Rafman’s contribution was from Canvas on Demand which prints digital images onto stretched canvas in Connor, “Post-Internet: What It Is and What It Was”, Kholeif, You are Here: Art After the Internet, p. 61 and accessed 18 March 2018, https://www.canvasondemand.com

26. Connor, “Post-Internet: What It Is and What It Was”, Kholeif, You are Here: Art After the Internet, pp. 61-62.

27. Higher Pictures, "Brand Innovations for Ubiquitous Authorship", accessed 15 March 2018, http://higherpictures.com/press/brand-innovations-for-ubiquitous-authorship/

28. Day, Lewis F., “Machine-Made Art”, Art Journal, (April 1885), pp. 107-110 at p. 107.

29. Fernández, María, “Detached from History: Jasia Reichardt and Cybernetic Serendipity”, Art Journal, Vol. 67, No. 3 (Fall 2008), pp. 6-23 at p. 2.

30. Fernández, “Detached from History”, Art Journal, p. 3.

31. Fernández, “Detached from History”, Art Journal, p. 3.

32. Hope, and Ryan, Digital Arts, p. 58.

33. Stakemeier, “Controlled Medium Specificity”, Ammer, Hochdorfer, Joselit, eds., Painting 2.0, p. 265.

34. Steyerl, Hito, “A Thing Like You and Me”, in Hudek, Anthony, ed., The Object, (Whitechapel Gallery, 2014), pp. 45-51 at p. 46.

35. Krauss, A Voyage on the North Sea, p. 6.

36. Joselit, David, “Reassembling Painting”, Ammer, Hochdorfer, Joselit, eds., Painting 2.0, pp.169-181 at p. 180.

37. Tromel, Brad, “Art After Social Media”, Kholeif, You are Here: Art After the Internet, p. 39.

38. Stallabrass, Julian, Internet Art: The Online Class of Culture and Commerce, (Tate Publishing, 2003), p. 44.

39. Stallabrass, Internet Art, p. 44.

40. Joselit, “Reassembling Painting”, Ammer, Hochdorfer, Joselit, eds., Painting 2.0, pp.169-181 at p. 179.

41. Marks, Laura U., Sensuous Theory and Multisensory Media, (University of Minnesota Press, 2002), p. 179.

42. Steyerl, “A Thing Like You and Me”, in Hudek, The Object, p. 48.

43. Hochdorfer, Achim, “How the World Came in”, Ammer, Hochdorfer, Joselit, eds., Painting 2.0, pp. 15-27 at p. 24.

44. Krauss, A Voyage on the North Sea, p. 10.

45. Galerie Sultana, accessed 18 March 2018, http://www.galeriesultana.com/artists/celia-hempton and Kholeif, “Electronic Superhighway”, p. 33.,

46. Stakemeier, “Controlled Medium Specificity”, Ammer, Hochdorfer, Joselit, eds., Painting 2.0, p. 265 and Ludlow 38, accessed 18 March. 2018, http://ludlow38.org/exhibitions/who-framed-sarah-szczesny/

47. Balsom, Erika, “On the Grid”, Kholeif, Electronic Superhighway, pp. 45-51 at p. 47.

48. McHugh, Gene, “The Context of the Digital: A Brief Inquiry into Online Relationships”, in Kholeif, You are Here: Art After the Internet, pp. 28-34 at p. 29.

49. Day, “Machine-Made Art”, p. 110.

50. Bauer, Will, and Gibson, Steve, “Objects of Ritual”, Moser, Mary Anne, and MacLeod, Douglas, Immersed in Technology: Art and Visual Environments, (The MIT Press, 1996), pp. 271-274 at p. 283.

51. Ammer, Manuela, “How’s My Painting?” (Judge Me, Please, Don’t Judge Me)”, Ammer, Hochdorfer, Joselit, Painting 2.0, pp. 85-101 at p. 152.

52. Ammer, Manuela, “How’s My Painting?” (Judge Me, Please, Don’t Judge Me)”, Ammer, Hochdorfer, Joselit, Painting 2.0, pp. 85-101 at p. 85.

53. Quantrill, Michael, “Drawing as a Gateway to Computer-Human Interaction”, Leonardo, Vol. 35, No. 1, (2002), pp. 73-78 at p. 73.

54. Reas, Casey, “The Language of Computers”, Maeda, John, Creative Code, (Thames and Hudson, 2004), p. 44.

55. Simon, “Authorship, Creativity, and Code”, Maeda, Creative Code, p. 46.

56. Wattenberg, Martin, “The Art of Visualisation”, Maeda, Creative Code, p. 78.

57. Manovich, Lev, “Software is the Message”, Journal of Visual Culture, Vol. 13(1), (2014), pp.79-81 at p. 81.

58. Krauss, A Voyage on the North Sea, p. 5-6.

59. Levin, Golan, “Is the Computer a Tool”, Maeda, Creative Code, p. 140.

Bibliography

Hochdorfer, Achim, Kraus, Karola, and Maaz, Bernhard, “Preface and Acknowledgements”, pp. 6-9,

Ammer, Manuela, Hochdorfer, Achim, and Joselit, David, “Introduction”, pp. 10-14,

Hochdorfer, Achim, “How the World Came in”, pp. 15-27,

Ammer, Manuela, “How’s My Painting?” (Judge Me, Please, Don’t Judge Me)”, pp. 85-101,

Joselit, David, “Reassembling Painting”, pp.169-181,

Pichler, Wolfram, “On the Art History of expression: The Example of Matisse’s “Notes of a Painter””, pp.244-249,

Stakemeier, Kerstin, “Controlled Medium Specificity: Networks and Painting”, pp. 262-267,

Kelsey, John, “The Sext Life of Painting”, pp. 268-271,

Ammer, Manuela, Hochdorfer, Achim, and Joselit, David, eds., Painting 2.0: Expression in the Information Age: Gesture and Spectacle, Eccentric Figuration, Social Networks, (Prestel, 2015).

Bowyer, Emerson, “Editor’s Introduction: Multiplying the Visual: Image and Object in the Nineteenth Century”, Grey Room, No. 48, (Summer 2012), pp. 6-11.

Pollock, Griselda, “Series Preface - New Encounters Arts, Cultures and Concepts”, pp. xiii-xviii,

Hayles, N. Katherine, “Traumas of Code”, pp. 23-41,

Bryant, Antony, and Pollock, Griselda, Digital and Other Virtualities: Renegotiating the Image, (I. B. Tauris & Co Ltd., 2010).

Morris, Robert, “Notes on Dance”, pp. 1-6,

Krauss, Rosalind, “The Mind/Body Problem: Robert Morris in Series”, pp. 65-110,

Bryan-Wilson, Julia ed., Robert Morris, (MIT Press, 2013).

Corcoran, Marlena, “Digital Transformations of Time: The Aesthetics of the Internet”, Fourth Annual New York Digital Salon in Leonardo, Vol. 29, No. 5, (1996), pp. 375-378.

Day, Lewis F., “Machine-Made Art”, Art Journal, (April 1885), pp. 107-110.

Fernández, María, “Detached from History: Jasia Reichardt and Cybernetic Serendipity”, Art Journal Vol. 67, No. 3 (Fall 2008), pp. 6-23.

Franco, Francesca, “Computational Art Exhibitions in London, 2014: A New Hope”, Visual Resources, Vol. 31, (2015), pp. 201-210.

Quantrill, Michael, “Towards an Understanding of Requirements for Interactive Creative Systems”, pp. 187-190,

Fujita, H., and Johannesson, P., eds., New Trends in Software Methodologies, Tools and Techniques, (IOS Press, 2002).

Galerie Sultana, accessed 18 March 2018, http://www.galeriesultana.com/artists/celia-hempton

Gere, Charlie, “New Media Art and the Gallery in the Digital Age”, accessed 5 March 2018, http://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/02/new-media-art-and-the-gallery-in-the-digital-age

Greene, Rachel, Internet Art, (Thames and Hudson, 2004). pa.

Greene Naftali gallery, accessed 9 March 2018, http://www.greenenaftaligallery.com/artists

Grew, Isabelle, and Lajer-Burcharth, Ewa, Painting Beyond Itself: The Medium in the Post-Medium Condition, (Sternberg Press, 2016).

Hertz, Paul, “Art, Code, and the Engine of Change”, Art Journal, Vol. 68, No. 1, (Spring 2009), pp. 58-75.

Higher Pictures, "Brand Innovations for Ubiquitous Authorship", accessed 15 March 2018, http://higherpictures.com/press/brand-innovations-for-ubiquitous-authorship/

Hope, Cat and Ryan, John, Digital Arts: An Introduction to New Media, (Bloomsbury Academic, 2014). ch

Hudek, Antony, “Introduction: Detours of Objects”, pp. 14-27,

Adorno, Theodor W., “On Subject and Object”, pp. 30-31,

Piper, Adrian, “Talking to Myself: The Ongoing Autobiography of an Art Object”, pp. 32-33,

Steyerl, Hito, “A Thing Like You and Me”, pp. 45-51,

Dorfles, Gillo, “The Man-Made Object”, pp. 71-74,

Hudek, Anthony, ed., The Object, (Whitechapel Gallery, 2014).

Kaganskiy, Julia, “Transfer Gallery Attempts to Crack the Digital Art Dilemma”, accessed 5 March 2018, https://creators.vice.com/en_au/article/aejmv5/transfer-gallery-attempts-to-crack-the-digital-art-dilemma

Blazwick, Iwona, “Electronic Superhighway”, pp. 20-23,

Kholeif, Omar, “Electronic Superhighway: Towards a Possible Future for Art and the Internet”, pp. 24-33,

Halter, Ed, “Time Frames: Three Episodes in the Evolution of Digital Cinema”, pp. 34-43,

Balsom, Erika, “On the Grid”, pp. 45-51,

Paik, Nam June in conversation with Leeson, Lynn Hershman, “Video Philosopher”, pp. 222-225,

Wiggen, Ulla in conversation with McCormack, Seamus, “Membrane of Mind”, pp. 240-248,

Barry, Judith in conversation with Perks, Sarah, “The Dynamics of Desire”, pp. 226-231,

Lund, Jonas in conversation with McCormack, Seamus, “Programming Subjectivity”, pp. 232-239,

Kholeif, Omar, ed., Electronic Superhighway: From Experiments in Art and Technology to Art After the internet, (Whitechapel Gallery, 2016).

Bridle, James, “The New Aesthetics and its Politics”, pp. 20-27,

McHugh, Gene, “The Context of the Digital: A Brief Inquiry into Online Relationships”, pp. 28-34,

Tromel, Brad, “Art After Social Media”, pp. 36-55,

Connor, Michael, “Post-Internet: What It Is and What It Was”, pp. 56-64,

Balsom, Erika, “Against the Novelty of New Media: The Resuscitation of the Authentic”, pp. 66-77,

Chan, Jennifer, “Notes on Post-Internet”, pp. 107,

Kholeif, Omar, You are Here: Art After the Internet, (Cornerhouse, 2014).

Krauss, Rosalind, “Two Moments from the Post-Medium Condition”, October, Vol. 116, (Spring 2006), pp. 55-62.

Krauss, Rosalind, A Voyage on the North Sea: Art in the Age of the Post-Medium Condition, (Thames and Hudson, 2000).

Krysa, Joasia, and Parikka, Jussi, Writing and Unwriting (Media) Art History: Erkki Kurenniemi in 2048, (The MIT Press, 2015).

Licklider, J. C. R., “Man-Computer Symbiosis”, IRE Transactions on Human Factors in Electronics, Vol. 1, (March 1960), pp. 4-11.

Lieser, Wolf, Digital Art, (Ullmann Publishing, 2009).

Ludlow 38, accessed 18 March. 2018, http://ludlow38.org/exhibitions/who-framed-sarah-szczesny/

Luke, Ben, “From pencil and paper to virtual reality: working from life today”, accessed 18 March 2018, https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/article/magazine-from-life-ben-luke

Reas, Casey, “The Language of Computers”, p 44,

Simon Jr., John, “Authorship, Creativity, and Code”, pp. 46,

Wattenberg, Martin, “The Art of Visualisation”, p. 78,

Levin, Golan, “Is the Computer a Tool”, p. 140,

Co, Elise, “Beyond pixels”, p. 172,

Rozin, Daniel, “Physical Computing”, p. 174,

Maeda, John, Creative Code, (Thames and Hudson, 2004).

Manovich, Lev, “Software is the Message”, Journal of Visual Culture, Vol. 13(1), (2014), pp.79-81.

Marks, Laura U., Sensuous Theory and Multisensory Media, (University of Minnesota Press, 2002).

Veale, Tony, Gervas, Pablo, and Perez y Perez, Rafael, “Computational Creativity: A Continuing Journey”, pp. 483-487,

Jennings, K. E., “Developing Creativity: Artificial Barriers in Artificial Intelligence”, pp. 489-501,

Forth, Jamie, Wiggins, Gearing A., and McLean, Alex, “Unifying Conceptual Spaces: Concept Formation in Musical Creative Systems” pp. 503, Minds and Machines: Journal for Artificial Intelligence, Philosophy, and Cognitive Science Vol. 20, No. 4, (Winter 2010).

Moser, Mary Ann, “Introduction”, pp. xvii-xxv,

Hayles, Katherine, “Embodied Virtuality: Or How to Put Bodies Back Into the Picture”, pp. 1-28,

Tenhaaf, Nell, “Mysteries of the Bioapparatus”, pp. 51-71,

Huhtamo, Erkki, “Time Traveling in the Gallery: An Archeological Approach in Media Art”, pp. 233-268,

Bauer, Will, and Gibson, Steve, “Objects of Ritual”, pp. 271-274,

Gromala, Diane J., and Sharir, Yacov, “Dancing with the Virtual Dervish: Virtual Bodies”, pp. 281-285,

Moser, Mary Anne, and MacLeod, Douglas, Immersed in Technology: Art and Visual Environments, (The MIT Press, 1996).

Paul, Christiane, Digital Art, (Thames and Hudson, 2015).

Petzel website, accessed 9 March 2018, http://www.petzel.com/artists

Costello, Diarmuid, “Automat, Automatic, Automatism: Rosalind Krauss and Stanley Cavell on Photography and the Photographically Dependent Arts”, Critical Inquiry, Vol. 38, No. 4, (Summer 2012), pp. 819-854.

Phelan, Andrew, “The Impact of Technology and Post Modern Art on Studio Art Education”, Art Education, Vol. 37, No. 2, (March 1984), pp. 30-36.

Quantrill, Michael, “Drawing as a Gateway to Computer-Human Interaction”, Leonardo, Vol. 35, No. 1, (2002), pp. 73-78.

Roberts, John, The Intangibilities of Form: Skill and Deskilling in Art after the Readymade, (Verso, 2007).

Stallabrass, Julian, Internet Art: The Online Class of Culture and Commerce, (Tate Publishing, 2003).

Stedelijk Museum, “Jana Euler, High in Amsterdam, the Sky of Amsterdam”, https://www.stedelijk.nl/en/exhibitions/jana-euler-high-in-amsterdam-the-sky-of-amsterdam

Tate, “About the Harwood De Mongrel Tate Site”, http://www2.tate.org.uk/netart/mongrel/home/siteguide.htm

Taylor, Grant D., When the Machine Made Art: The Troubled History of Computer Art, (Bloomsbury Academic, 2014).

Usselmann, Rainer, “The Dilemma of Media Art: Cybernetic Serendipity at the ICA London”, Leonardo, Vol. 36, No. 5, (2003), pp. 389-396.

Williams, Robert, Art Theory: An Historical Introduction, (Blackwell Publishing Limited, 2009).

Whitney Mueum of American art, accessed 25 Marc 2018, https://whitney.org/Exhibitions/WadeGuyton

Xu, Songhua, Lau, Francis C.M., and Pan, Yunhe, A Computational Approach to Digital Chinese Painting and Calligraphy, (Springer, 2009).

Paulsen, Kris, Here/There: Telepresence, Touch, and Art at the Interface, (The MIT Press, 2017).