A Susurration From The Future

Anna Alfut, Jessica Gould, Veera Jussila

Today, we tend to see plants as the Other: as decorations or as “wild” nature we can take advantage of or protect. Recently, however, the modernist distinction between nature and society has been subject to critical discussion.1 This includes the rise of post-anthropocentrism that Braidotti2 describes as “the politics of life itself”; life is seen as an open-ended process between species. This new direction is partly supported by advances made in science2: we now know that trees communicate via fungi network3 and are capable of having subjective experiences4. As a result, we are better prepared for considering what Marques5 calls parallel futures: the continuum that we already share with other livelihoods. We wanted to examine this continuum by using data of plants and humans.

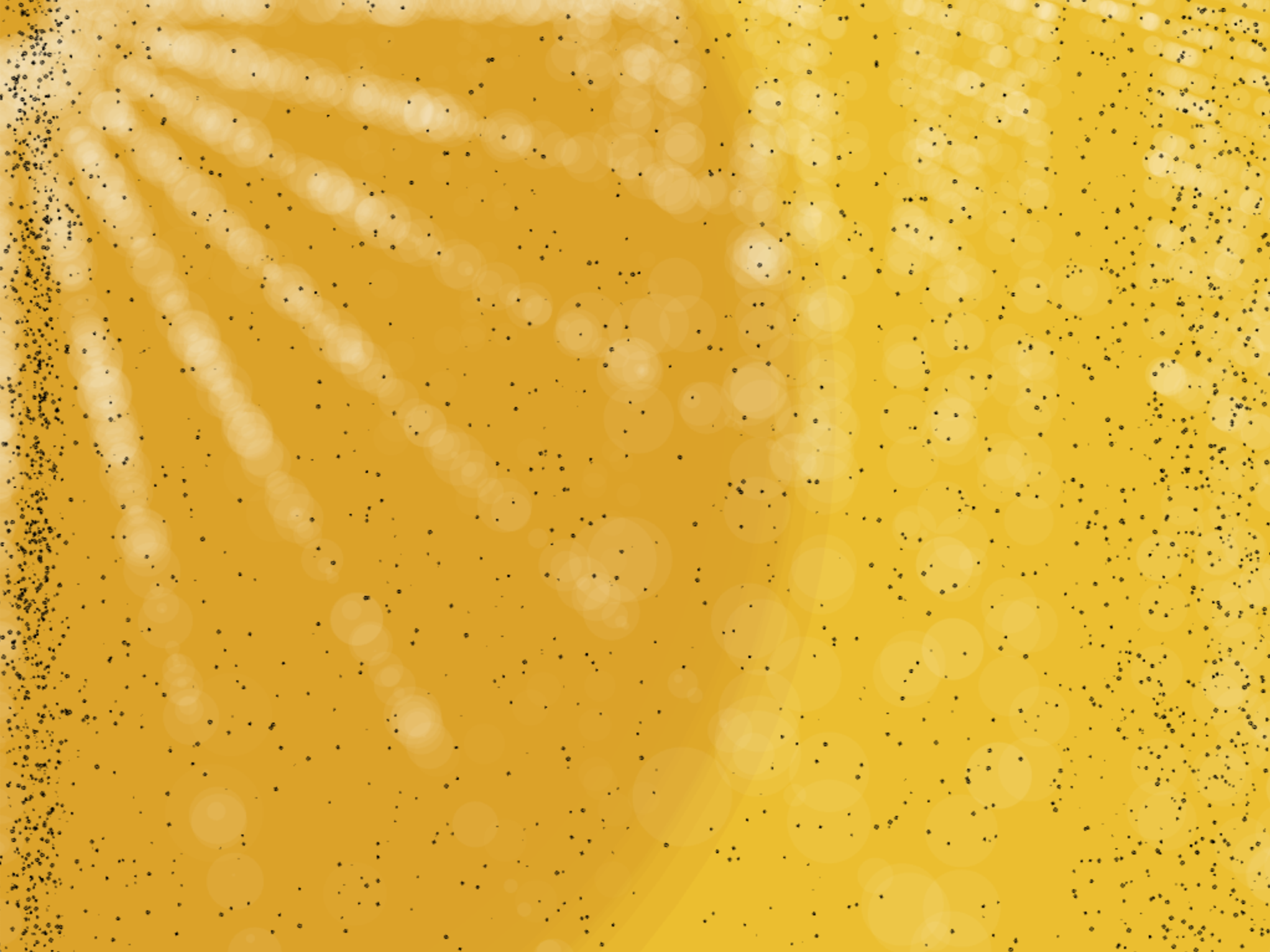

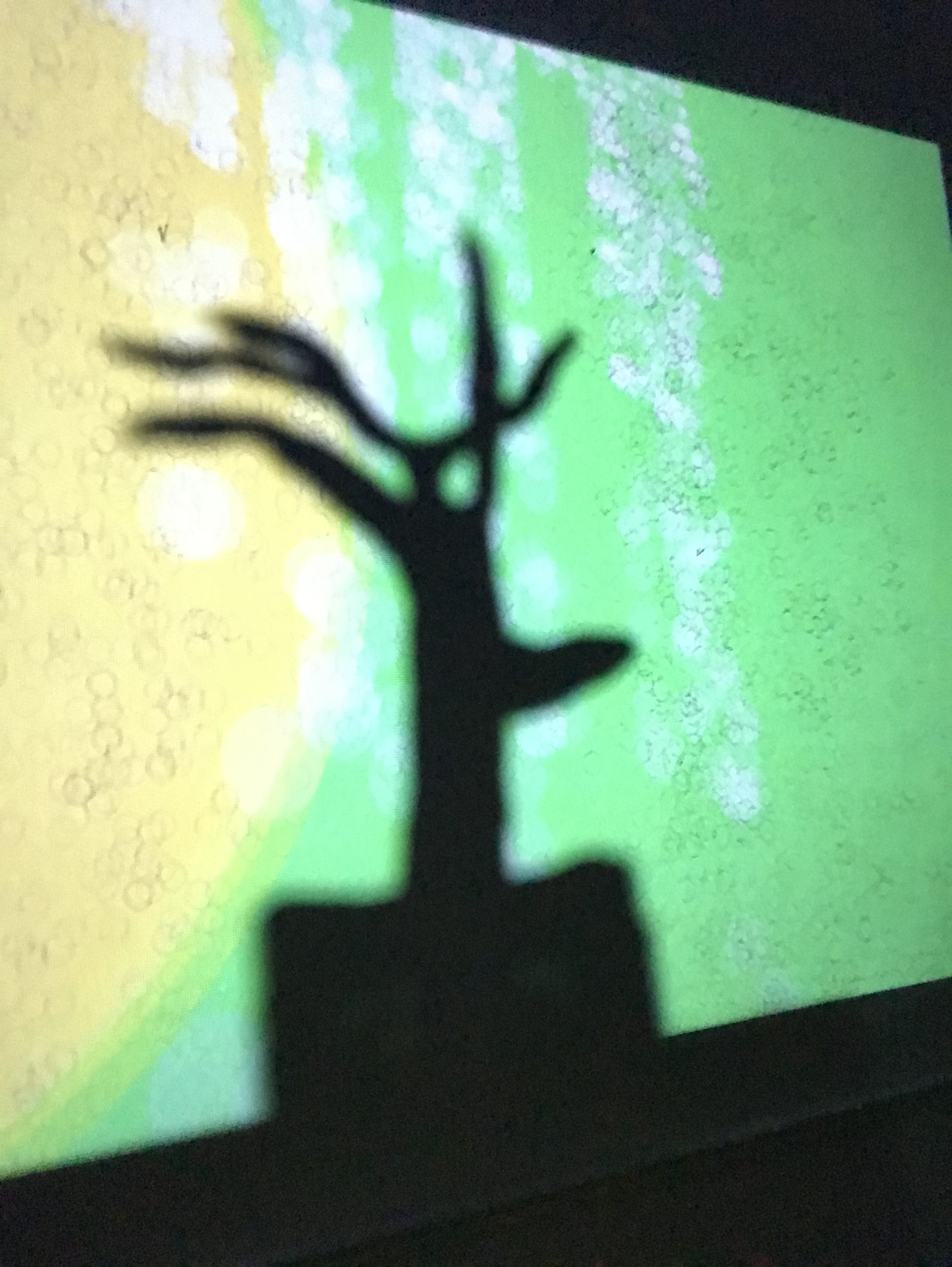

Aiming at situated knowledge, we chose to collect human and tree experiences of Kew Gardens, due to the special human-plant relationships that are performed.6 From the point of view of material semiotics, the web of actors included us, interviewees, trees that we tested or left out, the institution of Kew and many others. Our concern6 was to undo the dynamics where trees are the Other. Therefore, we recorded as serial data: human voices, the sound of the leaves in the wind and capacitive changes in a leaf caused by touch.This changed our relation to other actors; sensors literally acted as mediators, suiting the ideas of technology as a tool for posthuman subjectivity.2

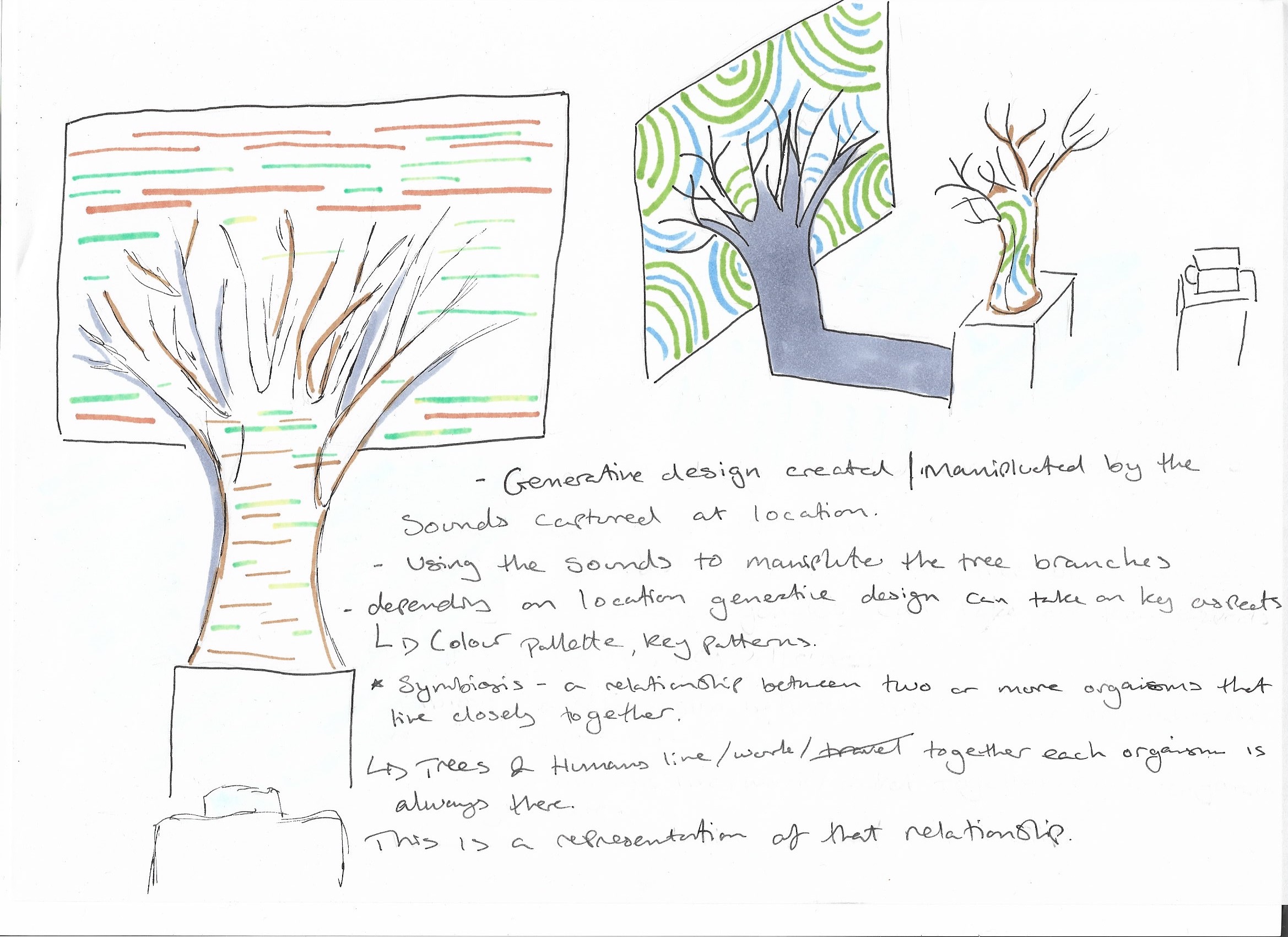

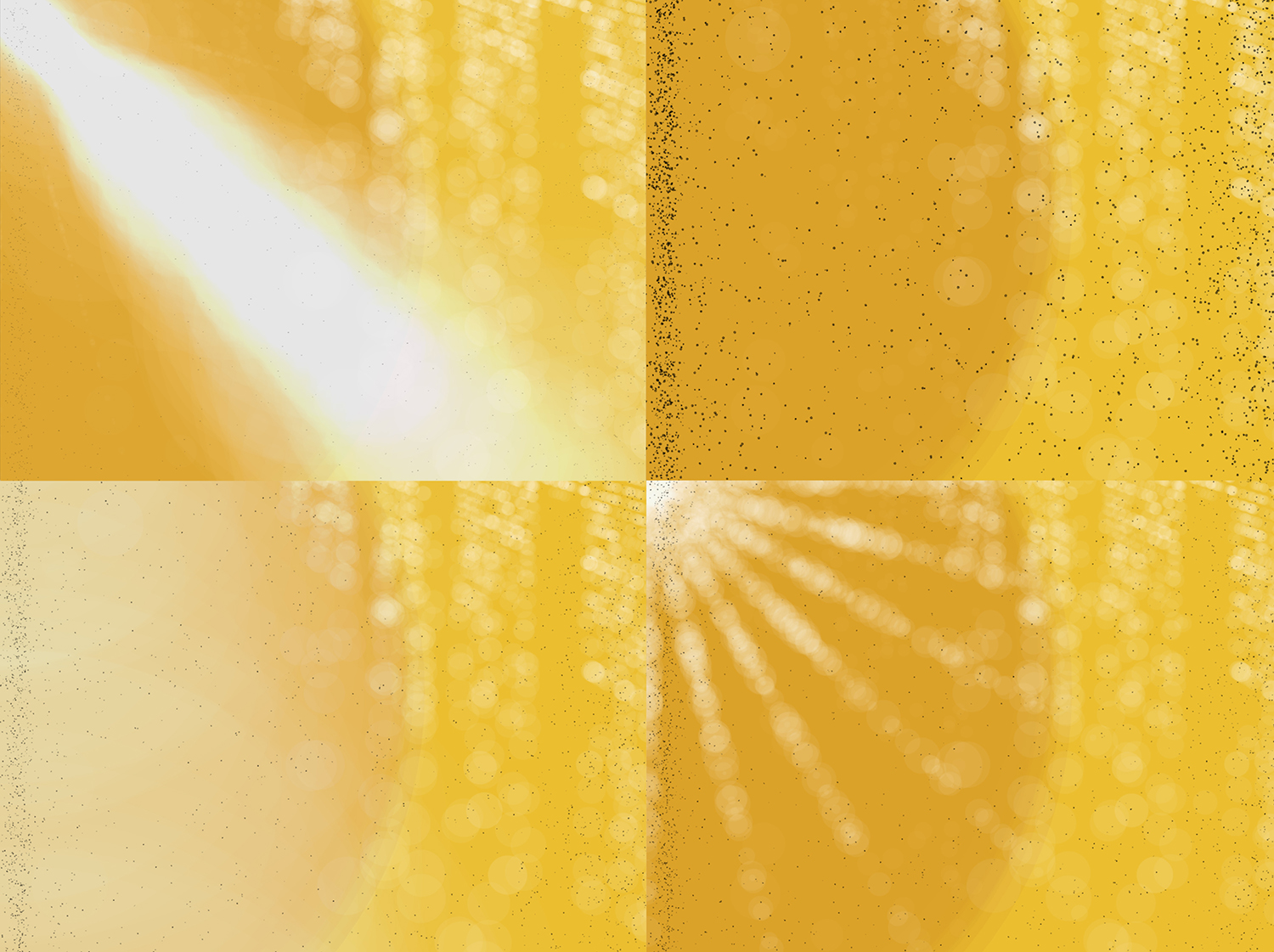

Algorithm became a central actor. One option could have been to create a GAN (generative adversarial network) where tree data acts as a discriminator for human data. This mixing could also partially tackle the problem of machine learning predictions being tied to the past.7 Not experienced in deep learning yet, we demonstrated the continuum using Openframeworks. Using a framework by Dorin et al8, we can divide our artefact into four parts. The data, animation and tree sculpture are our entities. Processes are run by the code: tree and human actors meet as vectors and Arduino makes the sculpture react to sounds. Environmental interaction consists of information flows: data from Kew and current sensory inputs. Sensory outcomes make entities and processes visible via arbitrary mapping, forming the installation. The site becomes one actor.

Theory was inseparable from our practice. We wanted to avoid anthropomorphism and compensatory humanism2 where plants are reduced to being “one” with humans. For example, using pictures “taken” by trees would be contradictory with our framework. We also had to reflect our paradoxical position with the algorithm: making datasets merge or collide would demonstrate our vision of the continuum. By connecting trees and humans with sound, we perhaps explored what Castro9 calls “critical and creative anthropomorphism” as a “means of becoming otherly human”. Maybe one could use sensory data for exploring the even more ambitious vision of geo-centric subject2 and human as a part of cosmic machine10.

Approaching post-anthropocentrism by computing made us aware of our position. The choice of not differentiating “tree-like” and “human-like” inputs can be both supported or debated with posthumanist theories. Secondly, all actors formed an organism: we as researchers asking the computer to envision the continuum, the data depending on trees and sensors. Being part of this interdependent system embodied our theory base. Braidotti2 encourages us to “become subjects that actively desire to reinvent subjectivity”; for us, the research itself became a test of a new kind of subjectivity.

More reflections in the podcast:

References

1. Pálsson, G. Human-environmental relations: orientalism, paternalism and communalism. In: P. Descola & G. Pálsson, ed. Nature and Society: Anthropological Perspectives. Routledge, 1996, pp. 64-65.

2. Braidotti, R. The Posthuman. Polity Press, 2012, pp. 60, 79, 81-83, 86, 90-93.

3. Simard, S. How trees talk to each other. TED conference, 2016. Retrieved from: https://www.ted.com/talks/suzanne_simard_how_trees_talk_to_each_other?language=en Accessed 13th December 2019.

4. Pereira, A. Jr. The experiential continuum: from plant sentience to human consciousness. PowerPoint presentation at Goldsmiths, University of London, 9th October 2019. Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/336210189_The_Experiential_Continuum_from_Plant_Sentience_to_Human_Consciousness Accessed 13th December 2019.

5. Marques, P. N. Parallel futures: one or many dystopias? E-flux, 2019, Journal #99. Retrieved from: https://www.e-flux.com/journal/99/263702/parallel-futures-one-or-many-dystopias/ Accessed 13th December 2019.

6. Law, J. Material semiotics. 2019. Retrieved from: http://www.heterogeneities.net/publications/Law2019MaterialSemiotics.pdf Accessed 13th December 2019.

7. Soon, W. Unerasable characters in machine learning. Guest lecture as part of IS71076B: Computational Arts-Based Research and Theory at Goldsmiths, University of London, 1st November 2019.

8. Dorin, A., McCabe, J., McCormack, J., Monro, G. and Whitelaw, M. A framework for understanding generative art. Digital Creativity, 2012, 23, pp. 239–259. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/14626268.2012.709940 Accessed 13th December 2019.

9. Castro, T. The Mediated Plant. E-flux, 2019, Journal #102. Retrieved from: https://www.e-flux.com/journal/102/283819/the-mediated- plant/ Accessed 12th December 2019.

10. Delueze, G. and Guattari, F. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Continuum, 2004, pp. 215.

+ Mentioned in the podcast:

Macfarlane, R., Richards, D. and Donwood, S. Holloway. Faber and Faber, 2014.