Presence of Biophony and Geophony in the Anthropocene

Produced by: Oliver Schilke

Abstract

The silence and disruption we hear in these natural soundscapes tell us stories of the haunted landscapes of the Anthropocene. Careful listening to animal vocalisation and geological sounds can tell us about the state of particular environments.

Drawing on my current exploration in natural ecology, I discuss an art-science research project that I am currently developing, whereby a computationally driven natural soundscape is affected by human noise in a room. This work is a reflection of the impact of climate change on Earth’s natural acoustic structure.

Introduction

Ghosts is one of two key themes in the book Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet[1]. It tells stories of landscapes haunted by the violence of modernity. “The winds of the Anthropocene carry ghosts - the vestiges and signs of past ways of life still charged in the present. Our ghosts are traces of more-than-human histories through which ecologies are made and unmade”[2]. I offer another story to this account, one in which the ghosts of the Anthropocene can be heard and understood though the soundscapes of our natural ecologies.

All around the Earth great quantities of animal species transmit sounds for communication, foraging and navigation, in particular. Sound is a defining component in animal behaviour that is utilised, for example, in territory defence, mate attraction, parent-offspring identification, orientation, prey localisation and predator escape[3]. Two elements of global soundscapes are being reshaped by climate change; biophony – including biotic sounds; and geophony – including abiotic yet natural sounds coming from Earth movement, water and wind[4].

How can we most suitably use our knowledge to limit our destruction of these soundscapes? The goals of this paper are to indicate the effects of climate change on elements of vocalising organisms and how through art science activism and environmental education we can better understand these landscapes we exist in and pay attention to the lives of multiple species around us.

Soundscape Ecology

The anthropogenic influence on the Earth’s climate creating greatly impacts on the speed in which changes occur in natural environments, hindering a majority of species to adapt[5]. Climate conditions play a major role in the propagation of animal sound. In their environments, sound speed depends on such frameworks as temperature, humidity, wind and rain intensity. Alterations in these frameworks can have huge implications on the range of communication between individuals[6]. Even small shifts in atmospheric conditions may have drastic consequences on vocal animals that may alter the distance at which acoustic signals can be recognised and decoded[7].

Acidification in marine systems and its effect on sound transmission of species is a well-known effect of climate change[8]. Marine mammals use low frequencies to communicate and the acidification of the water affects these low frequency sounds making it difficult for them to communicate. These marine animals are obligated to adapt their vocalisation by altering the frequency, duration and intensity in their communication tonavigate the effects of anthropogenic impact.

Anthrophony is another element of global soundscapes that is used to describe sound generated by humans. Studies have shown that sounds of the anthrophony (e.g. cars airplanes, machinery, railroad crossings, urban ambient noises, human noise etc) have an acoustic masking event on the biophony[9]. The acoustic overlap of human- and animal-induced sounds can cause huge disruptions in the ecology of natural habitats. This human noise can cause heavy burdens for vocalising animals. Anthropogenic noise and land use have been recognised as a significant threat to animal acoustics[10].

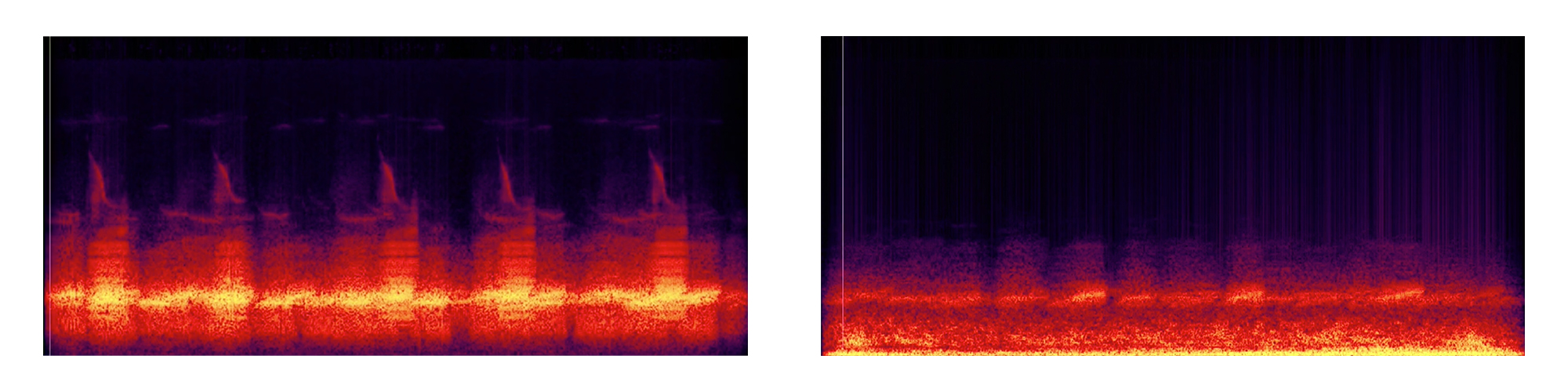

In a TED Talk by Bernie Krause[11], a leading pioneer in soundscape ecology, he gives a powerful example of this impact: In Mono Lake (east of Yosemite National Park) the Great Basin Spadefoot toads gather around large, vernal pools in great numbers. These toads vocalise in a chorus, in sync with each other. There are two reasons behind this: competitive, so they can look for a mate; and cooperative, because of their synchronicity it is difficult for predators such as coyotes, foxes and owls to single them out. The U.S. Navy fly jets very low over this habitat, the anthrophony from these jets bring about harmful effects for these chorusing toads. This disturbance causes the frogs to fall out of sync and masks their vocalisation making it hard for them to find a mate and allows predators to pick them off. Here I present two spectrograms from Krause’s findings (Figure 1), on the left you see the frog chorusing when it is a is in a healthy pattern, on the right you see a recording taken during jet flight in the distance, where you see breaks in their chorus and the masking jet signature in yellow at the bottom of the spectrograph. The frog population in the 1980s and early 90’s was previously diminishing, but due to less flights and habitat restoration their populations are close to normal[12].

Figure 1

The Haunted Biophony and Geophony & Art Science Activism

The acoustic niche hypothesis, stemming from the ecological niche concept[13], specifies that species in an environment occupy a certain acoustic territory to avoid interference from each other’s vocalisations The acoustic niche hypothesis could be narrated as a sympoietic arrangement. Donna Haraway’s term Sym-poiesis is simply defined as “making with”. Nothing is self-made, nothing is self-organising, nothing is auto-poietic. “Sympoiesis is a work proper to complex, dynamic, responsive, situated, historical systems. It is a word for worlding”[14]. Animals in selective habitats have developed their symbiotic acoustic assemblages, which are like a “knots of diverse intra-active relatings in dynamic complex systems”[14] both cooperative and competitive. These sympoietic arrangements that have taken millions of years to evolve are being undone in a heartbeat.

Art science activisms inspire greater environmental responsibility through the medium of art and demonstrate the power of their form[15]. Sympoietic thinking and action needs to become a part of art science activisms. Projects in the themes of art and science can demonstrate how art and environmental education can be intertwined and deliver a powerful story that can inspire and generate positive change.

Presence

In this vein of art science activism, I have developed my project -Presence. It refers to the state or fact of existing, the existence of multispecies kin, and being mindfully present, understanding our current state of anthropogenic influence, the present fact occurring. Etymologically the word ‘presence’ indicates to ‘being at hand’, referring to our cause for Staying with the Trouble.

[Due to the current circumstances of Covid-19 the quarantine has left me unable to test this programme as an installation so I will be describing the project in a speculative manner].

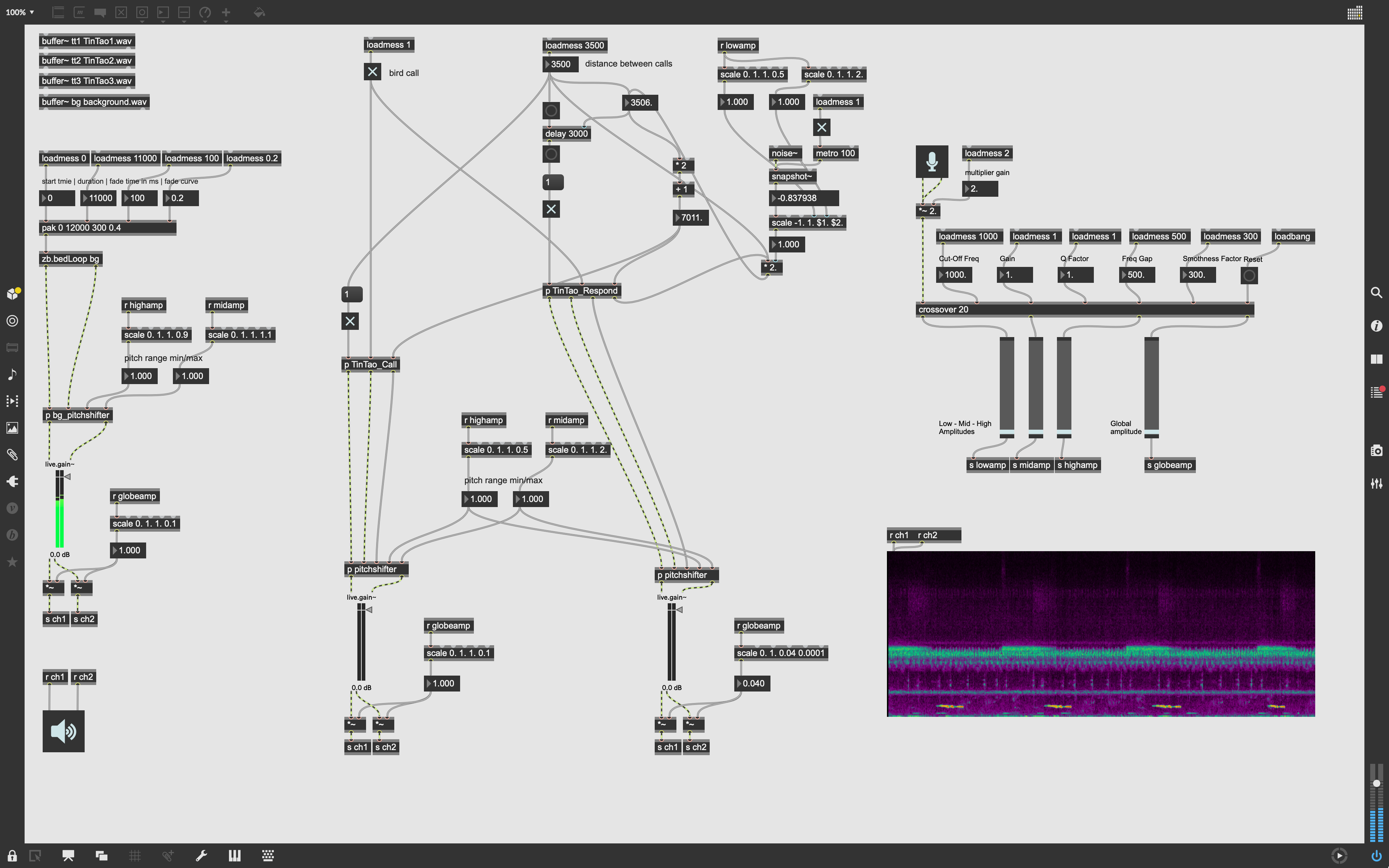

Presence is an ongoing project comprised of a computer generated biophony, that has been constructed in custom software using Max/MSP (Figure 2). The soundscape that is being generated comes from extracted samples of a recording in the Amazon Rainforest (https://freesound.org/people/felix.blume/sounds/408650/). These samples consist of background creatures (like crickets and birds) and the calls of the Grey Tinamou (Tinamus Tao) bird. This soundscape is to be heard as an installation, in which the participants in the space of the soundscape have a direct impact on the sound they are hearing.

While the background creatures play an important role in the ecology of the space - the dominate participant is of the Tinamus Tao bird. There is a back and forth response between what sounds like two of these birds communicating. The call can be interpreted as many things, for example, territory defence, mate attraction or parent-offspring identification. The important fact to consider here is what happens when the amplitudes of the frequencies in the space increase.

The amplitudes of the low, medium high and global frequencies of the participants are fed into the programme and processed as numerical data. This data in turn affects the parameters of the natural soundscape that is generated.

The amplitude of the medium and high frequencies in the room will disrupt the background creatures and the Grey Tinamou call normal pitch range by lowering and raising the range in which these samples can be played. The shift in pitch that occurs can be seen as a form of acoustic adaption in which the animals are having to change their frequencies so that the conflicting frequencies of the Anthropocene are not overpowering their own vocalisation.

The amplitude of the low frequencies will disturb the rhythms of the calls between the two Tinamus Tao samples by creating delays in response time and disruptions to their normal rhythms. This is a reflection on how high levels of anthrophony in a habitat make it difficult for vocalising animals, like birds, to communicate.

The reduction of the volume (what we hear) of the Tinamus Tao and background organisms correlates to the global amplitude of noise in the room. Here I set an example of the masking effects of the atherogenic noise impact that seem to overwhelm environments. The silence developed in this generated soundscape symbolise the haunted remains of the once flourishing bio- and geo-phonies. The landscape of the room is haunted by imagined futures, futures in which our multispecies kin have kept on diminishing.

Here I present two spectrograms recorded from this generative soundscape (Figure 3). The image on the left is a depiction of a healthy environment, you can see there are stable frequencies and amplitudes of the background creatures that cover the spectrum are stable, and the rhythms along with frequencies and amplitudes of the Tinamus Tao calls (which are visualised in yellow and red at the bottom of the graph) are also stable. On the right the image depicts what happens to these samples when the amplitude of all frequencies is high in the room. You can notice the alteration in the frequencies, the decrease of amplitude in both the background creatures and Tinamus Tao samples. It is also noted that the rhythms of the communication between the Tinamus Tao calls are drastically impacted.

By giving the participants the ability to have direct influence over this generated biophony, it gives them the chance to reflect on not only their own effects of environments around them but the effects of what is already around them on these surroundings. Presence reminds visitors of the value of natural sound and emphasises human connection to natural soundscapes and their environments, encouraging more attentive listening. It gives us a perspective from which to better understand our place in the ecology of soundscapes.

Figure 2

Figure 3

Conclusion

Climate change and anthropogenic noise are identified as major threats to biophonies and geophonies from pole to pole. With the rate of extinction increasing several hundred times beyond historical levels, for example, due to global warming and resource extraction, these great animal orchestras are vanishing.

These natural and generated soundscapes tell us stories of triumph and loss, connection and resilience. The dwindling orchestras show us a different story of the avarice and impetuousness of the Anthropocene. “As humans reshape the landscape, we forget what was there before"[2]. Through art science activism we can break oblivious realities that we find ourselves in and better understand our place in relation to our multispecies kin. The stories that we can tell of these soundscapes have the ability to draw us into new relations and forms of responsibility[16].

The aim of Presence is to get participants to listen to their environment, both the generated soundscapes, and the soundscapes of human noise in the space. A conversation occurs between these two soundscapes, the participant is given the collective ability to think about their relation to these creatures they are hearing and how the collective assemblage of people in the room together has the ability to make a difference. Just like in the Anthropocene, an individual might see themselves without the ability to make a difference to the effects of climate change, but inspiring people to understand that collective capability is the tool to create change can motivate people to implement this change.

In conclusion, understanding these natural soundscapes is an important practice to better understand the effects of climate change. More needs to be done in the Anthropocene to limit the effects humans have on the environment to protect our natural ecologies. Telling stories through art science activisms is an important method which we can use to bring inspiration to a wide range of people to think about their collective impact on these habitats. These practices can awaken people’s curiosity and better understand our multispecies entanglement.

Annotated Bibliography

Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet. (University of Minnesota Press, 2017).

Arts of living on a damaged planet is a book comprised of a collection of essays in two key themes: Ghosts, landscapes haunted by the anthropocene; and monsters, looking at interspecies connectivity. These essays build our understanding of the impacts of the anthropocene on natural environments and how we can understand the histories narratives behind them. They aim to inspire collective thought for the difficulties of the times we live in and how we can learn to build a more sustainable future.

Chung, S. K. & Brown, K. J. The Washed Ashore Project: Saving the Ocean Through Art. Art Education 71, 52–57 (2018).

The Washed Ashore Project is an art science activism project that inspires the development of environmental education through art project. It aims to tell the story of how plastic is having disastrous effects on our oceans, but through collective unity we have the ability to limit this destruction.

Sueur, J., Krause, B. & Farina, A. Climate Change Is Breaking Earth’s Beat. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 34, 971–973 (2019).

This essay is an analysis of the impacts of climate change and anthropogenic noise on natural soundscapes. The research shows that the health of natural habitats can be understood through their vocalisation, leading us to better understand the effects of the anthropocene on natural ecologies.

References

1. Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet. (University of Minnesota Press, 2017).

2. Introduction Haunted Landscapes of the Anthropocene. in Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet (eds. Tsing, A., Swanson, H., Gan, E. & Bubandt, N.) 1–14 (University of Minnesota Press, 2017).

3. Tobias, J. A., Planque, R., Cram, D. L. & Seddon, N. Species interactions and the structure of complex communication networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111, 1020–1025 (2014).

4. Sueur, J., Krause, B. & Farina, A. Climate Change Is Breaking Earth’s Beat. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 34, 971–973 (2019).

5. Parmesan, C. Ecological and Evolutionary Responses to Recent Climate Change. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 37, 637–669 (2006).

6. Gillooly, J. F. & Ophir, A. G. The energetic basis of acoustic communication. Proc. R. Soc. B 277, 1325–1331 (2010).

7. Krause, B. & Farina, A. Using ecoacoustic methods to survey the impacts of climate change on biodiversity. Biological Conservation 195, 245–254 (2016).

8. Hester, K. C., Peltzer, E. T., Kirkwood, W. J. & Brewer, P. G. Unanticipated consequences of ocean acidification: A noisier ocean at lower pH. Geophys. Res. Lett. 35, L19601 (2008).

9. Desrochers, L. & Proulx, R. Acoustic masking of soniferous species of the St-Lawrence lowlands. Landscape and Urban Planning 168, 31–37 (2017).

10. Quinn, J. E., Markey, A. J., Howard, D., Crummett, S. & Schindler, A. R. Intersections of Soundscapes and Conservation: Ecologies of Sound in Naturecultures. 22.

11. Krause, B. The Voice of the Natural World. (2013).

12. Stewart, J. & Bronzaft, A. L. Why noise matters : a worldwide perspective on the problems, policies and solutions. (Earthscan, 2011).

13. Hutchinson, G. E. An Introduction to Population Ecology. (Yale University Press, 1978).

14. Haraway, D. Symbiogenesis, Sympoiesis, and Art Science Activisms for Staying with the Trouble. in Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet (eds. Tsing, A., Swanson, H., Gan, E. & Bubandt, N.) 25–50 (University of Minnesota Press, 2017).

15. Chung, S. K. & Brown, K. J. The Washed Ashore Project: Saving the Ocean Through Art. Art Education71, 52–57 (2018).

16. van Dooren, T. & Rose, D. B. Lively Ethography: Storying Animist Worlds. Environmental Humanities 8, 77–94 (2016).